VOL. 26, No. 1

This conceptual paper critiques the popular Community of Inquiry framework (CoI) that is widely used for studying text-based asynchronous online discussion (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000). It re-examines the three main aspects of CoI (cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence) and their relationship, and further highlights the specificity and complexity of online discussion forums. The paper explains that the multi-functionality of communicative acts which often combine instruction, knowledge construction, and social interaction in a single utterance. It further argues that all online expressions are inherently social. It clarifies the confused relation of cause and effect in CoI and specifies the leadership functions of teaching presence and how they are intertwined with social and cognitive presence. A game metaphor and Gadamer’s notion of “play” are employed to explain the dynamics of online discussion forums. The article concludes with a discussion of the practical and methodological implications of its main arguments.

Cette étude théorique critique le populaire cadre de référence sur le Community of Inquiry (CoI) qui est largement utilisé pour l’étude des discussions asynchrones en ligne à base de texte. Celle-ci réexamine les trois volets principaux du cadre de référence CoI (présence cognitive, présence sociale et présence enseignante) ainsi que la relation entre ceux-ci. Elle met aussi en lumière la spécificité et la complexité des forums de discussion en ligne. L’article avance que le CoI sous-estime la multifonctionnalité complexe des actions communicatives qui font souvent simultanément appel à l’instruction, la construction du savoir et l’interaction sociale à chaque fois qu’on fait un énoncé. L’article clarifie la relation parfois floue entre la cause et l’effet dans le cadre de référence CoI et précise les fonctions de leadership qui sont attribuables à la présence enseignante, ainsi que comment ces fonctions sont entrelacées avec les fonctions sociales et cognitives. L’article avance aussi que la présence sociale est plus qu’un simple aspect ou une simple composante de la discussion en ligne; elle est la trame de fond de tout ce qui se passe. Malgré leur apparente intention, tous les énoncés faits en ligne ont par nature un caractère social. On fait la différenciation entre la nature plutôt non structurée de l’implication intellectuelle et le développement cognitif en quatre étapes adopté par le cadre de référence CoI. On présente la notion d’un niveau d’analyse spécifiquement communicatif et on emploie une métaphore de jeu ainsi que la notion de « fusion des horizons » de Gadamer pour expliquer les rouages de cette notion dans le cadre de forums de discussion.

The Community of Inquiry framework (CoI) for studying online asynchronous discussion (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000) has generated significant impact in both research and practice worldwide over the past ten years. The journal, Internet and Higher Education, has recently produced a special issue — The Community of Inquiry Framework: Ten Years Later (Swan & Ice, 2010). In an opening article (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2010) the three original authors reflect on the conception and evolution of CoI, followed by seven additional articles that report current research on the CoI.

Amid a rapidly growing body of research, a number of critiques of CoI have begun to emerge in recent years, including a self-critique by its principal author Randy Garrison, co-authored with J. B. Arbaugh (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007; Jézégou, 2010; Morgan, 2011; Rourke & Kanuka, 2009). In these critiques the authors inspect and extend CoI. They further call for the research community to continue examining the framework and the research activities generated, to reflect on their strengths and weaknesses, and to imagine new ways of advancing text-based online learning theories.

This article is an attempt at answering the call. I intend to re-examine the main aspects of the CoI and their relationship. I will reintroduce some relevant concepts originated by Andrew Feenberg in "The Written World" (1989) and apply other ideas presented in a more recent article, Pedagogy in Cyberspace: The Dynamics of Online Discourse, which we coauthored (Xin & Feenberg, 2006, 2007). I wish to further highlight the specificity and complexity of online discussion forums, with reference to theories of communication and Gadamer’s notion of “play.”

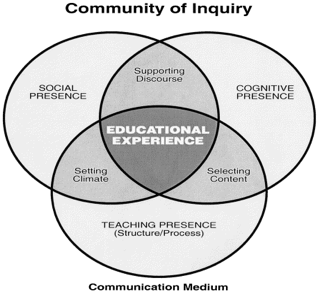

To begin this discussion, I will give a brief review of the CoI and its key components to provide the necessary context for the analysis. Garrison, et al. (2000) define the CoI as consisting of three key elements: cognitive presence, social presence, and teaching presence. Cognitive Presence is the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning through sustained reflection and discourse (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2001). Social presence is “the ability of participants in the Community of Inquiry to project their personal characteristics into the community, thereby presenting themselves to the other participants as ‘real people’” (Garrison et al., 2000, p. 89). Teaching Presence is the design, facilitation, and direction of cognitive and social processes for the purpose of realizing personally meaningful and educationally worthwhile learning outcomes (Anderson, Rourke, Garrison, & Archer, 2001). The CoI assumes that “learning occurs within the Community through the interaction of these three core elements.” (Garrison et al., 2000, p. 88). Figure 1 illustrates the framework.

Fig. 1: Community of inquiry framework.

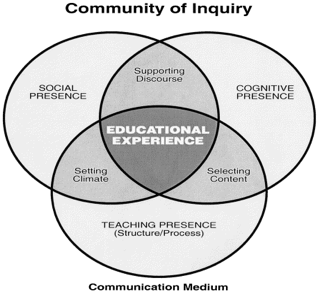

The authors also specify various categories and indicators of each of the three elements to provide a coding scheme for studying online transcripts (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: Community of inquiry elements, categories and indicators.

The identification of the social, cognitive, and teaching dimensions of discussion forums no doubt has a great deal of appeal. I suspect that its attractiveness at least to some extent is due to its simplicity, which appeals to common sense and to teachers who seek to give rational form to a lifetime of experience in classrooms. The parsimony of the coding schemes provides a useful analytical tool that has inspired volumes of online learning research in the past decade. The importance of this contribution cannot be overestimated.

However, much of the research done focuses on applying the coding schemes to the analyses of social, teaching and cognitive presences as separate and distinct aspects of online discussion and there are very few studies examining the three elements simultaneously (Garrison & Arbaugh, 2007, p. 159). There is a need to identify relationships among these elements and to recognize that online discussion is more subtle, complex, and messy than the coherent pattern presented in CoI. Online conversation consists in a flow of relatively disorganized improvisational exchanges that somehow achieves highly goal-directed, rational course agendas. A conceptual model of this phenomenon must reckon with both aspects — apparent chaos and order. Admittedly, the authors are well aware of this in a general way. But additional detailed discussion is needed to fully account for the complexity it implies.

Garrison, et al. (2000) and Garrison and Arbaugh (2007) anticipated many of the arguments that will be presented in this article. But they do not explicitly relate their insights to the underlying processes that are specific to text-based online discussion. One can easily argue that the three identified components in CoI could equally apply to any educational setting whether face-to-face or online. We need a theory that accounts for the specificity of the asynchronous educational forum and pulls together the aspects that CoI refers to. In this paper I propose a way of accomplishing this goal through distinguishing and analyzing the specifically communicative aspect of educational forums. By communicative aspects I mean not the content of what is communicated but the way it is communicated. Communication in this sense includes not only such obvious features as tone but also how each contribution provides a context for others’ communications. This is important because the way the content is communicated can encourage or discourage further responses.

The remainder of this article starts with a discussion of the multi-functionality of online talk and the concept of online presence. A set of communicative functions for moderating online discussion will be re-introduced from earlier studies by Feenberg (1989), Xin (2002), and Xin and Feenberg (2006, 2007). These sections lay a foundation for the further critique of two CoI components — social presence and teaching presence. Due to the limited space, my critique of cognitive presence of CoI and other stage-based cognitive development models of online discussion (e.g., Harasim, 1990; Gunawardena, Lowe, & Anderson, 1997) will be presented in a separate article. In my critiques of the social and teaching presence I will explain and demonstrate how each of the three CoI components is intertwined with the other two. A discussion of the practical and methodological implications of my main arguments concludes the article.

The first thing to emphasize is that educational computer conferences consist in exchanges in natural language. They resemble classroom discussions in a face-to-face context. And as with classroom discussions, each utterance online (i.e., a written word or statement) is first and foremost a communicative act that attempts to engage the interest and response of others (Feenberg, 1989). Typically in such discussions, whether face-to-face or online, each utterance performs multiple functions, for example, supplying information in a socially acceptable way in order to receive recognition and to provoke a reply.

The CoI does not explicitly reflect this functional entanglement of human communication. The failure to abstract the communicative level from the substance of the discussion and the background conditions, I suspect, is why much of the existing work focuses on one or another aspect of the framework rather than examining the interactions of the three elements. As a result, these studies primarily classify online utterances into one or another category depending upon whether the interpreter focuses on the social, teaching, or cognitive aspects of discourse. In fact utterances usually serve more than one purpose.

The distinctions between cognitive, teaching, and social aspects identified in the CoI framework are analytic rather than substantive or real, just like the named colors of a rainbow are an analytic abstraction of the real thing. The frequencies of the light in a rainbow are on a continuum; any attempt to name specific colors of the light misrepresents of the thing. That being said, the colors have their function. They provide a way of describing the rainbow and locating different areas within it. In online forums, the social, teaching and cognitive aspects are mingled together in a continuous flow — the communication process. The three aspects correspond to functions rather than to separate components. Analytic distinctions such as that between the rainbow’s colors or the functions of online utterances are useful for understanding the complexity of phenomena; however, they do not always correspond to neat distinctions in reality. Each of the three components of the CoI is an abstraction from the whole, i.e., the communication process. Often all three aspects are performed simultaneously in a single communicative act, e.g., a sentence or paragraph, their precise function depending on what said previously leading up to that point, the contexts, and the dynamics of the discussion.

Thus, like its face-to-face counterpart, online discussion seamlessly combines many speech acts in each utterance. For example, acknowledging receipt of a message in the form of a reply carries at least two different kinds of information back to its author: information about the material process of communication – the message got through; and information about the human relations of communication – someone noticed the message and judged it acceptable. If the exchange is semantically rich enough, subject-related information may also be conveyed by the response, advancing the communication process in which the interlocutors are engaged. These interactions have a further dynamic import: writing a message that is delivered and accepted encourages further activity in the forum (Feenberg, 1989). Such condensations of discursive functions are no exception to the rule — on the contrary they are typical of the multilayered complexity of human communication, either face-to-face or online.

To further illustrate this phenomenon, let us look at a typical forum scenario.

Jane: Following the learner-centered movement, the teacher’s role is believed to have shifted from “a sage on the stage” to “a guide on the side.” Must a teacher be one or either other? Can’t she be a “sage” on the side and a “guide” on the stage?

Bill: Jane, you said a teacher should be a “sage” on the side and a “guide” on the stage.” I like this twist. It makes a lot of sense to me. Why shouldn’t a teacher be a sage and a guide at the same time? I begin to think that all my best teachers fit the image. I would like to hear more of your thoughts on this. Could you elaborate?

In replying to Jane, Bill has done at least four things: 1) Bill acknowledges Jane’s contribution (teaching function); 2) Bill shows his friendliness and interest in what Jane had to say, thereby creating an open and amicable atmosphere for further dialogue (social function); 3) Bill connects his idea to Jane’s, thereby demonstrating his own intellectual engagement (cognitive function); and 4) Bill invites Jane to respond further (social function) and facilitates discussion (teaching function).

As one can see from the above example, this relatively short message effortlessly combines many communicative functions. These are the typical dynamics of online discussion. The reason for this entanglement is the dynamic character of online discourse, the unfolding of the dialogue over time. This is where the multi-functionality of human communication and the specificity of the medium appear most clearly. It is true that one can analyze each post and the utterances within a post without referring to the communicative function it serves but that would be to miss the flow of the discourse. Rather than assigning utterances to one category or another, it is more illuminating to examine the dynamics of the dialogue in terms of how it engages the participants at each moment and develops the subject matter over time. This is of critical importance because failing to engage the participants in further responses would lead to no further development of the subject matter. Analysis of the frequency of various forms of presence cannot show how participants are able to say things that provoke further responses in the making of a conference. This leads me to reintroduce the concept of “moderating functions” Andrew Feenberg defines in his “The Written World” (1989).

This article was an early attempt to understand the unique process of communication in asynchronous text-based educational conferences. One of the enduring insights of the article is the analysis of leadership (called “moderating”) in organizing successful online classes. This work is frequently cited in online education research but its true theoretical contributions are largely overlooked.

The article lists and analyzes “moderating functions.” The most important point the article makes is that these functions are not performed in separate messages or even separate utterances within a message but are interlaced with everything that goes on in the course of discussion. Moderating functions are communicative acts that are seamlessly combined with cognitive and social contributions to online discussion. They support the interaction that keeps discussion alive. Teachers and students alike perform these moderating functions. To emphasize their communicative nature and to avoid a one-sided emphasis on the teacher’s or the moderator’s responsibility for performing them, I will refer them here as communicative functions (CFs). In what follows, I will consider anyone who performs these functions to be “moderating.”

Here is a summary of the ten communicative functions under three categories. These ten CFs include the original eight moderating functions (Feenberg, 1989;) and two more functions (referring and assessing) identified in later work (Xin, 2002; Xin & Feenberg, 2006, 2007).

Contextualizing Functions: These functions provide a shared framework of rules, roles and expectations for the group and include such performances as stating the theme of the discussion and establishing a communication model (opening discussions), suggesting rules of procedure for the discussion (setting the norms), managing the forum over time (setting the agenda), and referring to online and offline materials (referring).

Monitoring Functions: These functions help participants know if they have successfully obeyed the groups’ norms and fulfilled the expectations laid down for them. They include such activities as referring explicitly to participants’ comments to acknowledge their contributions (recognition), soliciting comments from individuals or the group (prompting), and assessing or providing feedback on participant accomplishment (assessing).

Meta Functions: These functions have to do with the management of process and content and include such activities as repairing communication links (meta comments), summarizing the results of intellectual engagements (weaving), and assigning specific roles to participants (delegating).

Based on this description, we can easily see that Jane, quoted in the previous example, performs the following functions:

From the context of the discussion, one can determine whether Jane responds to previous message(s). If so, she also performs the recognition function.

Similarly in Bill’s case, he performs: recognition (acknowledging what Jane said), assessing (judging what Jane said as valid) and prompting (questioning, inviting Jane to say more). Both Jane and Bill thus perform social, teaching and cognitive functions.

In this example, each communicative function (CF) performed by either Jane or Bill shares a single purpose: to engage further responses. By referring to the learner-centered movement and specifically “a sage on the stage” and “a guide on the side,” Jane provides not only contextual information but also an operative component — a hook — for others to respond to. This invitation is reinforced by Jane asking two prompting questions: “Must a teacher be one or either other? Can’t she be a ‘sage’ on the side and a ‘guide’ on the stage?” The performance of these two CFs indeed produces an effect: Bill replies. He acknowledges what Jane says by way of everything he says (i.e., recognition), judges its validity — “It makes a lot of sense to me. Why shouldn’t a teacher be a sage and a guide at the same time? I begin to think that all my best teachers fit the image.”(i.e., assessing) and further prompts, “I would like to hear more of your thoughts on this. Could you elaborate?” Having been recognized and encouraged, Jane is likely to further engage by posting a second response. This exchange between Jane and Bill may draw others into the dialogue.

As one can see rather than categorizing what Jane and Bill say based on social, teaching, and cognitive presence, the above analysis illustrates the dynamics of an online exchange in terms of how it advances the topic of the learner-centered movement and engages its participants. Rather than chunking the text into bits and pieces, the analysis relies on examining the context and the flow of the conversation. Through this, one can see how each communication function performed contributes to the to-and-fro movement of call and response that lies at the heart of educational forums.

In order to study the relationship and interaction of the three components of the CoI, one has to reinterpret the meaning of “presence” and sharpen its focus. The definitions of “presence” associated with the three components in the CoI framework are problematic for several reasons.

Every online communication is a manifestation of presence, regardless of what is said. Similarly, the only way to be present online is to communicate. Garrison et al. (2000) describe cognitive presence as "the extent to which learners are able to construct and confirm meaning," and social presence as "the ability of the participants to project themselves as real people" (emphases added). But the mere ability of learners to do these things is not sufficient to constitute presence. Presence must be constructed through actual communicative acts that perform various social, pedagogical, and cognitive functions. Similarly, “instructional management” and the “design and organization” of content and activities provide the capacity for teaching presence, but do not constitute it. Rather, teaching presence is constructed through activities such as presenting topics of discussion (i.e., opening discussions) and facilitating discourse by way of performing communicative functions such as recognition, prompting, assessing and weaving.

Why does this distinction matter? It has to do with identifying what is operative or at work in the medium as opposed to capacities or desiderata that may or may not be active forces in the communication process. Abilities are not the same as performances. Knowing a rule is not the same as obeying the rule. The CoI encourages one to think about what a successful conference would entail, but it does not adequately account for how to get there or make it happen. The communicative functions provide the operative means for accomplishing that. They are important for clarifying what one can and must do online so that participants are able to play their part in a successful educational experience.

For example, “open communication,” identified as a category under social presence, is established not by a rule or declaration of intention but by the way we actually speak to each other. “Risk-free expression,” as one of its indicator, is enabled by recognition. If someone is acknowledged rather than ridiculed when saying something daring or making a mistake, this creates an atmosphere in which everyone feels comfortable expressing oneself freely.

Desired states of affairs such as “open communication” are descriptors that may or may not apply in any given situation no matter how much they are referenced as goals. This is why modeling behavior is important. A teacher could say, "Feel free to speak up" but until someone does so (e.g., by saying something daring) and is accepted as normal (e.g., acknowledged by the teacher), the norm is only an unrealized ideal. Again, this is an example of how communicative functions (CFs) operationalize a rule or a desired state of affairs. “Presence” must be understood as just such an operative component of the discourse. In this sense, the cognitive, social, and teaching presences are best specified in terms of the functions that make them “present.” “Presence” is an effect of what I call “functions.” In other words, CFs are actions that cause the effect of someone or something being present.

In the following sections, I will develop this and the multi-functionality arguments through a critique of two of the three components of CoI: social presence and teaching presence.

Social presence was seen to perform a supportive role when the CoI was originally presented (Garrison et al., 2000). Reflecting on a number of the recent studies on social presence (Anagnostopoulos, Basmadjian, & McCrory, 2005; Beuchot & Bullen, 2005; Celani & Collins, 2005; Garrison & Cleveland-Innes, 2005; Molinari, 2004), Garrison and Arbaugh (2007) recognize that the role of social presence is more than merely supportive and is necessary for cognitive presence. I argue that because of the social nature of all communication, sociability is implicit in everything said online.

Social presence is classified under three categories: affective expression, open communication and group cohesion. Clearly, Col is correct to point out the importance of open communication and group cohesion. While these are necessary to get a job done, the role of affective expression (e.g., through means such as emoticons) is less clear. Furthermore, strictly speaking, there is no such thing as “risk-free expression” in a classroom situation, face-to-face or virtual. This is because everything said is context dependent and therefore subject to interpretation and misinterpretation. The emphasis on affective expression and absence of risk gives the impression that the authors see online classes as tightly knit communities. This is not what is usually observed in online classes. In the later self-critique, Garrison and Arbaugh (2007) admit that group cohesion does not flow from emotional bonds but rather from task focus, usually under the leadership of the teacher.

The three categories of social presence also confuse action with outcome. Affective expressions are communicative actions that can cause certain effects. Open communication and group cohesion are not actions but positive effects or outcomes of successful forum management. Putting the three together confuses cause (what one does) and effect (what the action leads to) and obscures what a participant should (or should not) do online in order to achieve the desired state of affairs.

As I argued earlier, what goes on in discussion forums has to be seen and interpreted through the lens of communicative acts. This observation leads to a consideration of what should be accounted as social and, more generally, the nature of online sociality.

Garrison et al. (2000) see the transactional nature of collaborative construction of knowledge at the heart of the CoI framework. This observation deserves to be specified more precisely. Online classes are more like a work group or sports team than a social club. Affective expression in this context should be or is primarily about recognizing the value of others’ contributions, such as what Bill says to Jane (i.e., “Jane, you said …. I like this twist. It makes a lot of sense to me”). Given the unique characteristics of the medium, explicit recognition is essential for continued participation. Recognition is a form of communicative intervention that assures an author that her message is received. This leads beyond interpersonal relationship to the sociality of online discussion. The true sociality of online talk lies in the to-and-fro moves of dialogue that resembles sports and games (Feenberg, 1989). The players may aim at a goal external to the play, such as winning, but what keeps them going from moment to moment are their moves and counter-moves. At each round of play their moves are provoked by previous responses and at the same time, hopefully, provoke further responses for intrinsic reasons such as the excitement of volleying with another player. Each message in educational dialogue fulfills a double goal: to communicate a content and to evoke further response. The true pleasure of “playing” at online discussion consists in making moves that keep others playing (Feenberg, 1989, p. 27).

Gadamer too (2004) argues that “play” lies at the heart of every conversation. The back and forth talk among the group members in an online discussion resembles relaxed volleying rather than a serious match. One wants one’s volleys returned and the aim is not so much winning as improving one’s game. The to-and-fro movement “is not tied to any goal that would bring it to an end,” instead, the movement of playing that has no goal “renews itself in constant repetition” (Gadamer, 2004, p. 104). Such dialogue games draw the players into “the mode of being of play” (p. 102): one becomes so focused on the back-and-forth of play that consciousness of the larger goal is “curiously suspended” (p. 102). The play plays the player. “In play, we do not express ourselves, but rather, the game itself ‘presents itself’” (p. xiv).

Erving Goffman (1961) employs the terms “absorption” and “engrossment” to describe the force that draws people into a game. Feenberg (1989) argues that successful online discussion has a comparable fascination. Engrossment is due to the enjoyment of the process of dialogue for its own sake. In educational forums such engrossment, I argue, is largely due to a successful development of the subject matter at hand through collaborative discourse among the participants. What enable a kind of temporary online community in education is not so much bonds of sentiment formed from personal intimacies, but engrossment in an intellectually charged dialogue game. This, in turn, creates the emotional bond of the learning community (Xin & Feenberg, 2006, 2007). More often than not, where the online discussion is unsuccessful, this too can be explained in terms of the game metaphor: the “players” have failed to get into the spirit of the game and view it ironically or merely instrumentally.

Once we understand online utterances as moves in a game and understand the intrinsic motives afforded by these moves, it is easy to recognize that each and every utterance performs a social function – whether it is a comment on a person’s holiday, an acknowledgement of someone’s earlier comment, an encouragement for further discussion, or a “pure” intellectual exchange. Furthermore, the sum of all that is said creates a social milieu, a backdrop and necessary conditions for further exchange. CoI recognizes that what projects a person as “real” is much more than her affective expressions, but it does not recognize the inherently social character of everything expressed online.

However, in educational forums, the social conditions that allow conversation to flow productively do not just happen. They require intentional and responsive invention by the teacher. This is a fact recognized by many, including Anderson, Rourke, Garrison and Archer (2001), Blignaut & Trollip (2003), Dixon, Kuhlhorst, & Reiff (2006), Garrison & Cleveland-Innes (2005), Kanuka, Rourke, & Laflamme (2007), Lim & Barnes (2002), Meyer (2003), Murphy (2004a), and Shea, Li, & Pickett (2006), just to name a few. In the following critique of the concept of teaching presence, I will bring into relief the specific importance of the communicative functions performed by teachers and students alike to enable a conference to flow and to advance its educational agenda.

Teaching presence in CoI is defined as design and organization, facilitation of discourse, and direct instruction. These are important aspects of the teacher’s work in the online class, but the core dynamics of online leadership requires further specification.

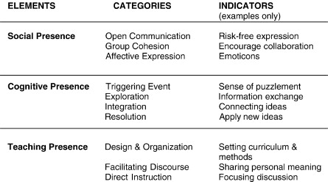

Earlier I raised the concern that from a strictly communicative perspective, “instructional management” and the “design and organization” of content and activities such as “setting curriculum and methods” (Garrison, et al, 2000, p. 89) contribute to the learning experience but do not constitute the teacher’s presence online since the only way to be present online is to express oneself in words. This is important because no matter how thoughtfully a conference is designed and structured, without the active involvement of the teacher in the process of dialogue, its success is left to chance. I further argued that instead of focusing on rules or desired state of affair (what to do), it is more helpful to operationalize the rules and desiderata in terms of communicative functions (how to do it). In other words, instead of discussing teaching presence as an effect, examine teaching functions that produce that effect. Anderson, Rourke, Garrison and Archer (2001) describe many indicators for measuring or assessing the characteristics of teaching presence. All these indicators can be mapped to Feenberg’s (1989) moderating functions to which I referred earlier. The significance of Feenberg’s work is its recognition of the communicative functions that enable the flow and advancement of online conversations. The CoI indicators perform these functions but the functions themselves are not identified in the model. Table 1 shows how some of the 18 indicators of the three categories of teaching presence map onto the communicative functions. Examples of the indicators are drawn from Anderson et al. (2001).

Table 1. Mapping of sample teaching presence indicators to communicative functions (CFs)

Teaching Presence |

Sample Indicators |

CF |

| Instructional Design and Organization | Establishing time parameters (e.g., Please post a message by Friday…”

Establishing netiquette (e.g., “keep your message short”) |

Setting the agenda

Setting the norms |

| Facilitating Discourse | Identifying areas of agreement/disagreement (e.g., "Joe, Mary has provided a compelling counter-example to your hypothesis. Would you care to respond?") | Recognition |

| Seeking to reach consensus/understanding (e.g., "I think Joe and Mary are saying essentially the same thing") | Weaving, recognition | |

| Encouraging, acknowledging, or reinforcing student contributions (e.g., "Thank you for your insightful comments") | Recognition | |

| Setting climate for learning (e.g., "Don't feel self-conscious about 'thinking out loud' on the forum. This is a place to try out ideas after all.") | Setting the norms | |

| Drawing in participants, prompting discussion (e.g., "Any thoughts on this issue?" "Anyone care to comment?") | Prompting | |

| Direct Instruction | Present content/questions (e.g., "Bates says…what do you think") | Referring; prompting |

| Focus the discussion on specific issues (e.g., "I think that's a dead end. I would ask you to consider…") | Meta comments | |

| Inject knowledge from diverse sources, e.g., textbook, articles, internet, personal experiences (includes pointers to resources) (e.g., "I was at a conference with Bates once, and he said…You can find the proceedings from the conference at http://www….") | Referring |

From Table 1 we can see that indicators under the Instructional Design and Organization category correspond to Contextualizing Functions. The indicators under Facilitating Discourse correspond mostly to the Monitoring Functions. Those under Direct Instruction correspond to Contextualizing and Meta Functions. Anderson et al. (2000) list many actions one should perform online but they do not explain the specific CFs of these actions that enable online conversation to proceed. As a result the list lacks a rationale; it is not clear why some items are on the list and others are not. When the actions are related to their communicative functions the CoI account becomes more than a list; it becomes a theory of the dynamics of the online conferencing. This also helps with classifying actions that appear ambiguously to belong to more than one category of indicators; for example, it is unclear why an indicator such as “focusing discussion on a specific issue” is treated as Direct Instruction rather than Facilitating Discourse. In addition, some of the indicators described under Facilitating Discourse such as “identifying areas of agreement/disagreement” and “seeking to reach consensus/understanding” are pedagogically oriented.

In a recent survey study of teaching presence using factor analysis (“Directed Facilitation,” Shea, 2006) data were collected from over 2000 students across multiple institutions. The study attempted to validate the three components of teaching presence but found that Facilitating Discourse and Directed Instruction resolved into a single factor. However, a separate study using essentially the same survey instrument developed by Shea, Fredericksen, Pickett and Pelz (2003), confirms the distinction between the three categories of teaching presence (Arbaugh & Hwang, 2006). Garrison (2007) attempted to explain the divergent results of the two studies. He suggested that it may be due to the nature of analysis used, undergraduate students’ limited ability to distinguish between facilitation and direct instruction, or the failure to control for some important factors. The argument of this article raises concerns about the second study. Since pedagogical effects can be fulfilled not only by Directed Instruction but also by Facilitating Discourse, while Direct Instruction can Facilitate Discourse, the distinction between them is inherently difficult to track. From a functional point of view, the first result seems more plausible, and not simply due to the difficulty undergraduates have making a distinction which this article shows to be questionable in the first place.

The current method of analysis chooses sentence, paragraph or message as the unit of analysis. The choice among these particular units of analysis is largely arbitrary. But such an approach does not take context fully into consideration. Therefore we cannot see the full functions of an expression. As one can see in Table 1, some of the expressions serving as examples of indicators of Facilitating Discourse or Direct Instruction perform multiple communicative functions. This would be clear if they were examined in context. Let us re-examine the earlier example of the exchange between Jill and Bill using Anderson et al.’s indicators (2001).

In this example we can see that Jane is performing Direct Instruction by “presenting content/questions” (Must a teacher be one or the other? Can’t she be a “sage” on the side and a “guide” on the stage?), “focusing the discussion on specific issues” (teacher’s roles), and “injecting knowledge from diverse sources” (from “a sage on the stage” to “a guide on the side.”). If we consider the context of the discussion (i.e., what is said earlier and what is to follow in Bill’s response), it is apparent that Jane is also facilitating discourse by “seeking to reach consensus/understanding” and by “drawing in participants, prompting discussion.”

Similarly, Bill performs both Direct Instruction (presenting content/questions, confirming understanding through assessment and explanatory feedback, and injecting knowledge from various diverse sources) and Facilitating Discourse (identifying areas of agreement/disagreement, encouraging/acknowledging/reinforcing contributions, setting climate for learning by way of encouraging/acknowledging/reinforcing, and drawing in participants by prompting discussion.) Even when we focus a single sentence of Bill’s posting — “Why shouldn’t a teacher be a sage and a guide at the same time?” — we can see that he performs both Direct Instruction and Facilitating Discourse.

The above analysis demonstrates that facilitation of discourse and direct instruction are inseparable aspects of teaching. Content and process are not separate entities. The way content is delivered affects the communicative process. For example, explaining something in a way that opens up new questions will keep the conversation going. In contrast explaining in a conclusive way may end the conversation. Similarly, norms can be established by explicit expressions (e.g., “keep your message short”); or they can be established by the teacher modeling the desired behavior without saying anything (e.g., writing messages no more than a few paragraphs long rather than a page long). Defining a concept may relieve anxiety among students unsure if they are using it correctly far better than a message urging everyone to relax. Encouraging a student may take the form of explaining ideas presented in her contribution, rather than praising her. Assigning a task to the group may only work if the task is clearly described, and that may involve quite a bit of cognitive intervention. And so on.

The highly context-dependent nature of online discussion also explains why facilitation is not just instructional, or social, or intellectual; it is often all of them simultaneously. Process and content are intertwined at the communicative level. Teaching presence both sustains the social relations of communication and advances understanding of the subject matter at hand. Because the messages that perform communicative functions often encapsulate cognitive contributions, the effective use of those functions fulfills an intellectual as well as a communicative role. This is why poor moderating contributes to the pervasive phenomenon of shallow engagement of learners (Fahy, 2005; Friesen, 2009; Rourke & Kanuka, 2007; Rourke & Kanuka, 2009).

In this paper I have critiqued the popular Community of Inquiry framework (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000) which is widely used for studying text-based asynchronous online discussion. Online discussion consists of a flow of relatively disorganized improvisational exchanges that somehow achieve highly goal-directed, rational course agendas. Despite its differences from face-to-face talk, participants routinely establish norms that impose a certain coherence and a personal character similar to conversational interaction (Herring, 1996, 1999). In this critique of CoI, I have explained how the apparent chaos and order are in fact one and the same process of knowledge construction combining the informal logic of conversation with the formal rationality of academic discourse.

My main arguments are the following. Online discussion must be understood as foremost a communication phenomenon. It consists of conversation exchanges in natural language. Online expression, like its face-to-face counterpart is multi-functional. We often combine instruction, knowledge construction, and social interaction in a single utterance. As demonstrated throughout the article, because of the multi-functionality of communication the three main aspects of the CoI — cognitive presence, social presence and teaching presence are intertwined.

By clarifying the nature of presence online, I draw attention to causes and their effects in discussion forums. Communicative functions (CFs) such as recognition, prompting, assessing, weaving, etc. are actions that lead to the presence of a participant or a thought or feeling. By making clear such cause and effect relations, one can readily see the active forces that advance online dialogues.

All communication is inherently social regardless of apparent intentions. Online discussion is no exception. The true sociality of educational online forums lies in the to-and-fro movement of the dialogue game and the intrinsic motives that emerge from the dynamics of online discussion on its own terms.

CFs are explained in contrast to teaching presence. These functions often encapsulate social, teaching and cognitive presence. They not only maintain the social relations of communication but also contribute to and advance the intellectual engagement of the participants.

Practical Implications

The practical implications of my arguments concern what teacher and students should do in a conference to make it productive. The method described here responds to the fact that communication must be continuously and intentionally produced. It is not a natural event even in face-to-face contexts, much less in the far more fragile online environment. A face-to-face class starts and ends at a specified time and it is presumed to be more or less successful by default if the students show up and stay until the end. Online, a conversation easily ends if no one keeps it going. Failure is self-evident and commonplace. To maintain a continuous flow of conversation, the participants must keep working at it by posting comments that invite further posts. The flow of online conversation is an achievement, produced through a collective effort. And like other collective efforts, it benefits from good leadership. The need for facilitation is much more pronounced online than in the face-to-face environment where habits are well established and paralinguistic cues fulfill many communicative functions. Murphy (2004b) makes it clear “that in order for the highest-level collaborative processes to occur within an OAD [online asynchronous discussion], there must be explicit strategies or techniques aimed at promoting these processes” (p. 429). The exercise of CFs is such an explicit strategy. It not only compensates for the missing paralinguistic cures but also carries out social, pedagogical and intellectual functions.

Methodological Implications

These observations have implications for how one analyzes online discourse. Language is always used for something. Primarily, language functions as a communicative event (Coulthard, 1994). Under the CoI, one analyzes communicated content; in addition, I argue that we need to look at communicative functions. A communicative function can be performed in a sentence, a paragraph or a whole post and with many different types of contents. Depending on the context, an expression (e.g., a sentence, a paragraph, or a post) may have to be coded under multiple functions (social, pedagogical, and intellectual). This is because often one function is performed implicitly in the course of an explicit performance of another function. Therefore the researcher must be prepared to enter into the details of the discussions and to understand the issues involved in order to identify the intertwined performances that support ongoing dialogue.

Furthermore, the analysis of the communicative functions of online talks should be considered together with other aspects of interest — who said what, how, why and when. The analysis of the exchange between Jane and Bill serves as an example. Such multi-dimensional examinations, especially combined with data visualization techniques, go beyond the content analysis techniques typically used in research on online discussions. This allows one to map the processes of communicative interaction and intellectual development over the course of a conference. It enables us to understand the structure of discourse, the organization of talk, the development of co-constructed dialogic meaning, breakdowns in communicative patterns, and examinations of the multilayered cultural and social implications of discourse (Mazur, 2004).

In order to study educational achievement online, whether in the form of individual learning gains or group convergence, a critical dimension that must be considered is time and order. Using examples from computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) research, Peter Reimann’s (2009) article "Time is Precious: Variable- and Event-centred Approaches to Process Analysis in CSCL Research" presents persuasive arguments and powerful illustrations of why and how examinations of the temporality of interaction, communication, learning, and knowledge construction can yield valuable insights into these complex processes.

Advances in conversation analysis (Clark & Schaefer, 1989; Mazur, 2004; Schegloff, 1991), computer-mediated discourse analysis (Herring, 1996, 1999, & 2004), and CSCL methodology (Cress, 2008; Reimann, 2009) should inform and aid the study of text-based asynchronous computer conferencing in multiple productive ways. (A separate article will offer a more detailed and fuller account of this topic.)

There is still much investigation to be done regarding our understanding of the contexts, content, and structure of participant interaction, social relationships and intellectual development in online forums. Such investigations will require increasingly sophisticated methods, both qualitative and quantitative, and will no doubt enhance our understanding of how best to design and conduct these online forums.

Walter Archer (2010), one of the three original authors of CoI, has published “Beyond online discussions: Extending the community of inquiry framework to entire courses” in the Special Issue on the Community of Inquiry Framework: Ten Years Later. Ironically, what we need is not to “go beyond” but rather come back and revisit and reconsider discussion forums as a critical medium for online learning on its own terms. We need to re-examine the dynamics of online dialogue and fully explain its unique educational potentials. I hope this paper has served toward this purpose.

Cindy Xin is an Educational Consultant at the Teaching and Learning Centre, Simon Fraser University. E-mail: cxin@sfu.ca