VOL. 34, No. 2 2019

Abstract: Only weeks before the 2019 annual meeting of the American Education Research Association (AERA) was held in Toronto, Ontario, the provincial government announced a major reform of education for that province entitled Education that Works for You – Modernizing Classrooms. From an e-learning perspective the proposal called for a centralization of e-learning, a graduation requirement of four e-learning courses, and increasing the class size limit for e-learning courses to 35 students. The AERA call for submissions for the 2020 meeting issued a challenge for scholars to ‘connect with organizational leaders to examine collaboratively continuing educational problems... [and] programmatically engaging with educational organizations.’ This article accepts that challenge and describes a collaboration between scholars and a pan-Canadian organization to examine the research behind each of these proposed e-learning changes. Based on that collaboration, the authors explore the existing system of e-learning in Ontario and highlight the concerning lack of details in many aspects of the proposal, as well as a lack of research to support the proposed actions.

Keywords: online proctoring, learning, test anxiety, worry, emotionality.

Résumé : Quelques semaines seulement avant la tenue de l'assemblée annuelle 2019 de l'American Education Research Association (AERA) à Toronto, en Ontario, le gouvernement provincial a annoncé une importante réforme de l'éducation pour cette province intitulée « L'éducation qui marche pour vous - Moderniser les classes ». Du point de vue de l'apprentissage en ligne, la proposition préconisait la centralisation de l'apprentissage en ligne, l'obligation d'obtenir un diplôme pour quatre cours d'apprentissage en ligne et l'augmentation de la taille maximale des classes pour les cours d'apprentissage en ligne à 35 étudiants. L'appel à soumissions de l'AERA pour la rencontre de 2020 a lancé aux chercheurs le défi de " se connecter avec les leaders organisationnels pour examiner de manière collaborative les problèmes éducatifs continus.... et] s'engager de manière programmatique avec les organisations éducatives. Le présent article relève ce défi et décrit une collaboration entre des chercheurs et un organisme pancanadien pour examiner la recherche qui sous-tend chacun des changements proposés concernant l'apprentissage en ligne. En se fondant sur cette collaboration, les auteurs explorent le système actuel d'apprentissage en ligne en Ontario et soulignent le manque de détails concernant de nombreux aspects de la proposition, ainsi que le manque de recherche sous-tendant les mesures proposées.

Mots-clés : surveillance en ligne, apprentissage, test d'anxiété, inquiétude, émotivité

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

The 2020 annual meeting of the American Education Research Association (AERA) call for submissions issued a challenge to, “in 2020 let us harness possibilities and choose as a body of scholars to reconnect with organizational leaders to examine collaboratively continuing educational problems. By reconnecting… we do mean programmatically engaging with educational organizations” (Walker, Croft, & Purdy, 2019, p. 1). It is somewhat ironic that this “power and possibilities for the public good when researchers and organizational stakeholders collaborate” themed conference immediately followed the 2019 annual meeting in Toronto, Ontario, which was held only weeks after an announced major reform of education for that province entitled Education that Works for You – Modernizing Classrooms (Government of Ontario, 2019a).

As a part of this announcement, there were significant changes announced to the system of K-12 online learning, or what is referred to as e-learning in the province. In the months following the announcement, the proposed e-learning changes became a particularly contentious issue in the popular media and on social media. Given that only approximately 5% of secondary students enroll in an e-learning course in Ontario (Barbour & LaBonte, 2018; Kapoor, 2019), many within the education system and much of the general public were simply ignorant when it came to what was e-learning, how had it been enacted in the province, and the nature of student success in this environment. This ignorance led to a lot of limited information and outright misinformation being accepted as fact. The purpose of this article was for the authors to engage with the Canadian eLearning Network (CANeLearn)i to examine the aspects of the proposed changes in relation to e-learning and explore the nature of the current system. Further, the authors will also critically explore the research into the proposed e-learning changes in an effort, as scholars, to engage with this educational community.

On 15 March 2019, the Government of Ontario announced the Education that Works for You – Modernizing Classrooms proposed policy. From an e-learning perspective, the proposed policy called for:

The government is committed to modernizing education and supporting students and families in innovative ways that enhance their success. A link to e-learning courses can be found here: www.edu.gov.on.ca/elearning/courses.html.

Starting in 2020-21, the government will centralize the delivery of all e-learning courses to allow students greater access to programming and educational opportunities, no matter where they live in Ontario.

Secondary students will take a minimum of four e-learning credits out of the 30 credits needed to fulfill the requirements for achieving an Ontario Secondary School Diploma. That is equivalent to one credit per year, with exemptions for some students on an individualized basis. These changes will be phased in, starting in 2020-21.

With these additional modernizations, the secondary program enhancement grant will no longer be required. (Government of Ontario, 2019b, ¶ 9-12).

Either as a part of, in conjunction with, or simply at the same time, the Government also embarked on a consultation process focused on class sizes in Ontario and invited public comment. There were four goals established for this consultation process:

- Student Achievement: Success and well-being of every child.

- Protecting Front Line Staff: The planned changes are to be managed through attrition protection for teachers.

- Fiscal Responsibility: Delivering services in an effective and efficient manner.

- Evidence-based Decision Making: Grounded in sound policy, inter-jurisdictional scans, and empirical research. (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2019a, p. 2)

Given the AERA’s 2020 thematic focus, it would seem that the focus on ‘evidence-based decision making’ would be a call to scholars to ‘connect with organizational leaders to examine collaboratively continuing educational problems.’ As a part of the consultation guide that was circulated, the proposed changes at the secondary level included:

Grades 9-12

| Grades | Current Status |

Proposed Changes |

Grades 9-12 |

|

|

The government remains committed to modernizing education while continuing to support students and families. In addition to the planned changes in the table above, starting in 2020-21, the government plans to centralize the delivery of all e-learning courses to secondary students in Ontario to allow students greater access to programming and educational opportunities. Secondary students will take a minimum of four elearning credits out of the 30 credits to fulfill the requirements for achieving an Ontario Secondary School Diploma. That is equivalent to one credit per year, with exemptions for some students on an individualized basis. This will include increased class size for online courses to 35 students. (p. 5)

Based on these proposed changes, the Ministry asked for public input on the following questions.

Consultation Questions:

- What are the opportunities of the planned changes in relation to the four key goals?

- The new vision for e-learning is intended to provide more programming options for students. What comments and advice do you have?

- Class size caps exist in many local collective agreements. Do these caps pose a barrier to implementing the new class size requirements?

- Are there other comments on the planned changes, keeping in mind the four key goals, you would like to provide? (p. 6)

Essentially, from an e-learning perspective the proposed changes called for a centralization of e-learning, a graduation requirement of four e-learning courses, and increasing the class size limit for e-learning courses to 35 students. However, before any examination of the research to support these proposed changes, it is important to understand the system of e-learning that currently exists within the province.

It is important to begin by underscoring the fact that e-learning in Ontario is not a student in a room by themselves or at home, logged into a computer where they complete online content without interacting with a teacher online or another human in person — as has been implied by some in the popular media (Durkacz, 2019; Farhadi, 2019a; Jones, 2019; Powers, 2019; Rivers, 2019; Syed, 2019). This is the old correspondence model of distance education, which still does exist in Canada — even in Ontario in small pockets (Barbour & LaBonte, 2018). Fortunately, distance education in Ontario has evolved considerably with the advent of e-learning. While the exact origins are disputed, it is safe to say that the first K-12 e-learning programs in the province began in the mid-1990s (Barker & Wendel, 2001; Barker, Wendall, & Richmond, 1999; Smallwood, Reaburn, & Baker, 2015). In 2000, several of the school boards that had been independently operating e-learning programs came together to co-operate on course development and student enrollment through the Ontario Strategic Alliance for e-Learning, which would later evolve into the Ontario e-Learning Consortium by the 2005-06 school year.

In 2004, the Ministry of Education began to take a more active role by surveying of all of the distance education courses being offered throughout the province, and eventually hosting a provincial learning management system (LMS) and creating a standard e-learning course content that all school boards could use provided they followed the guidelines laid out in the Provincial e-Learning Strategy. According to the Ontario Ministry of Education (2013):

E-learning refers to the use of the tools of the Provincial vLE/LMS when there is a scheduled distance between the e-learning teacher and students and/or students and each other. Distance may be related to location (i.e. students from different locations enrol in one e-learning course) or time (i.e. students from one location enrol in one course but access it during different periods of the day). (p. 2)

The key points in this definition are that the student and subject matter expert teacher are separated by distance (i.e., location or time), and instruction is provided through technology-mediated tools.

The definition for e-learning does not mention any other humans or any supports that the e-learning program or the school may or may not provide. However, the Ministry of Education also provided guidance on how schools should implement e-learning that includes:

This list includes a significant amount of human interaction — both in person and online, as well as a lot of support that schools and school boards were required to provide in order to be allowed to use the Ministry of Education’s tools and resources in their e-learning programs.

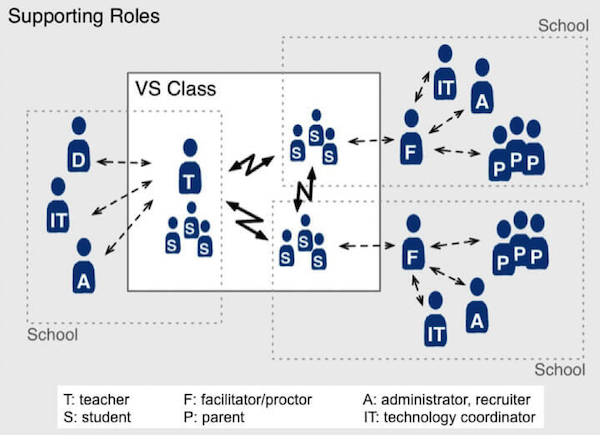

What this list of required interactions and supports should create is an environment like the one illustrated below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. In this kind of environment, the students (S) are enrolled in one of three brick-and-mortar schools. The online teacher (T) is also enrolled in one of these three schools. At each school, the students have access to the school-based administrator (A), local IT support (IT), and a facilitator (F). Finally, the original designer of the online course content (D) also happens to be in one of these three schools (although that is not usually the case, and we suspect they were added to the graphic to round out the representation of the different educator roles often found in the K-12 online learning environment). (Davis & Niederhauser, 2007)

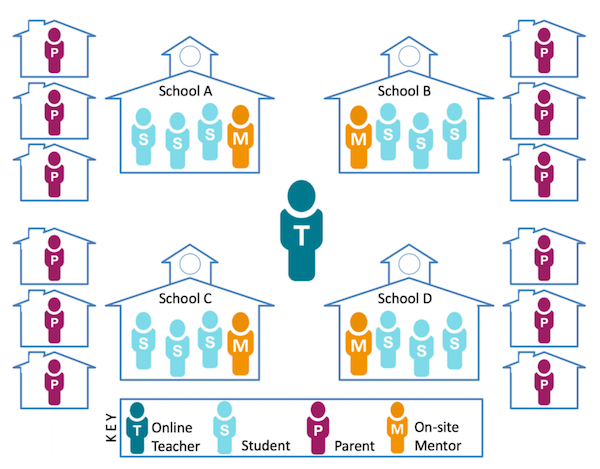

A more recent model has been developed based on research that has focused on schools in Michigan (i.e., the first jurisdiction in North American to have an online learning graduation requirement), and looks slightly different but contains many consistent elements (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. In this model, there are students (S) attending four separate schools, who are being taught by an online teacher (T) that isn’t based in any of the four schools. In each of the schools there is a mentor (M). As is the case with all students, in some of the homes there is a parent/guardian (P) that is able to help and provide some support, but in other cases that source of support is not available for any variety of reasons.

(Borup, Chambers, & Stimson, 2018)

In both models, the presence of a school-based individual (i.e., facilitator or mentor) is included — as is required in e-Learning Ontario’s Master User Agreement.

Barbour and Mulcahy (2004) described the role of this facilitator or mentor as providing initial maintenance and technology troubleshooting; to provide support (although not academic support) in gaining the independent learning and self-motivation skills that may be needed to succeed in the online environment; and to proctor tests and exams, monitor student attendance and behavior, and provide supervision; while Ferdig, Cavanaugh, DiPietro, Black, and Dawson (2009) described the role as assisting in registering and accessing virtual courses, providing academic tutoring and assistance to students, facilitating technical support, and acting as an academic advisor to students enrolled. In a detailed fashion, Borup, Chambers, and Stimson (2018) wrote this of the facilitator or mentor:

On-site mentors are not meant to replace the online teacher but to enhance and support the work that online teachers are currently doing. On-site mentors’ physical presence also allows them to provide types of support that are difficult for online teachers. More specifically, as the content experts, teachers are primarily charged with providing students with content-related support. Teachers are also responsible for assessing students’ understanding of the course material and their ability to apply their understanding in authentic ways. On-site mentors are primarily charged with developing relationships with students and motivating them to engage fully in learning activities. Mentors are also charged with helping students develop the communication skills, organizational skills, and study skills to effectively learn online. When working with multiple students, mentors can also promote co-presence and collaboration… [The online] teacher’s primary responsibility is to teach the content, and mentors’ primary responsibilities are to ensure “everything is working smoothly and order is maintained… In practice, there is “considerable overlap” between online teachers’ and on-site mentors’ facilitating efforts, and on-site facilitators can at times act as teachers and online teachers can act as facilitators. (¶ 4)

The present model of e-learning that exists in most programs in Ontario is consistent with the requirements outlined by the Ministry of Education, which is reflected in the images and descriptions above. According to the annual State of the Nation: K-12 e-Learning in Canada reports, during the 2016-17 school year there were approximately 65,000 students or about 5% of the overall population of secondary school students that were enrolled in one or more e-learning courses (Barbour & LaBonte, 2018). This finding was consistent with a report released by People for Education, who reported that there were approximately 4.6% of secondary students enrolled in e-learning courses during the 2018-19 school year based on their survey of “1,254… elementary and secondary schools in 70 of Ontario’s 72 publicly funded school boards, representing 26% of the province’s publicly funded schools” (Kapoor, 2019, p. 12).

It is also important to note that while there are in-person interactions in these e-learning models, this is not blended learning as has been claimed by some in the media (Paikin, 2019; Syed, 2019). Blended learning is defined by the Ontario as:

E-learning is distinct from blended learning. Blended learning refers to the use of the tools of the Provincial vLE/LMS that intersect with the teaching and learning in a scheduled face-to-face classroom. Unlike e-learning classes where there is a scheduled distance between students and teacher and/or students and each other, blended learning occurs within the context of an assigned face-to-face class in one board with daily physical attendance. (p. 3)

Within the research literature, the most commonly accepted definition of blended learning is Graham’s (2006) definition, which states that, “blended learning systems combine face-to-face instruction with computer-mediated instruction,” such as online learning (p. 5). The key focus in these definitions is the fact that the teacher, who has the subject matter expertise and provides the content-based instruction, is located in the same place and time as the students. Thus, the above models, due to the fact that the teacher is separated from the students by geography and/or time, meet the Ontario definition of e-learning (and the definition of online learning based on the larger field [Barbour, 2019a]). Unfortunately, there is no formal tracking of students engaged in blended learning in Ontario schools. The only data that is available is the number of unique student logins in the provincial LMS, indicating the number of students that may be using the Ministry of Education content with their teachers. During the 2017-18 school year there were approximately 565,000 logins, and at least 50,000 of these were students completing eLearning courses (Barbour & LaBonte, 2018). However, this does not mean that any of the 565,000 students were actually engaged in blended learning, only that they had the ability to be involved.

There are three e-learning issues that have been raised as a part of the Government of Ontario’s Education that Works for You – Modernizing Classrooms proposed changes. The following sub-sections examine each in detail. ii

The proposed change that CANeLearn had been queried about was whether a centralized model of e-learning is more effective than a decentralized model. As outlined by the State of the Nation: K-12 e-Learning in Canada annual reports (Barbour, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013; Barbour & LaBonte, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018; Barbour & Stewart, 2008), there are a variety of organizational models that are used across Canada. Less populated jurisdictions tend to utilize a centralized model of e-learning (e.g., Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, the Northwest Territories, and the Yukon) — often operated directly by the Ministry of Education or by a body designated by the Ministry of Education to have a provincial/territorial scope. Other jurisdictions have a more decentralized model where school districts or school board operate e-learning programs (e.g., British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Ontario). Finally, there are jurisdictions that have some combination of the two models (Quebec and Manitoba) — although in the case of Manitoba the centralized models use legacy forms of distance education, while its online learning program is primarily district-based.

While Ontario has been classified as a more decentralized model, this does not tell the full story. Unlike British Columbia, Alberta, and Saskatchewan, in Ontario it is only the operation of the e-learning program that is decentralized. The resourcing of these e-learning programs is quite centralized. According to the Ontario profile on the State of the Nation: K-12 e-Learning in Canada website:

Since 2006, the Ontario e-Learning Strategy has guided the Ministry of Education to provide school boards with various supports necessary to provide students with online and blended learning opportunities. The Francophone version of the strategy, Apprentissage électronique Ontario, was released in 2007. Under this policy, the Ministry provides school boards with access to a learning management system and other tools for the delivery of e-learning, asynchronous course content and a variety of multimedia learning objects, and a variety of other technical and human resource supports (including a “Technology Enabled Learning and Teaching Contact” in each school board). School boards delivering either online or blended learning must sign a “Master User Agreement” to access all of these services. (see ¶ 2 at https://k12sotn.ca/on/)

Essentially, e-Learning Ontario (a unit of the Ministry of Education) centrally provided all of the tools and content needed to deliver e-learning, and even provided each school board with human resources to encourage the use of these services. The only decentralized role in the existing system for school boards was the determination of which courses were offered, the selection of the individual teachers to provide instruction in those courses, and the enrollment of students into the centralized learning management system. However, even many of these individual school board-based programs cooperate with other school boards throughout the province as a part of the Ontario eLearning Consortium, Ontario Catholic eLearning Consortium, and/or Consortium apprentissage virtuel de langue française de l’Ontario to maximize their online offerings by sharing course offerings, resources, and students. The reality is that the existing system in Ontario is already highly centralized.

To date, there has not been a lot research published on the effectiveness of e-learning based on the organizational model. Most of the research has focused on whether distance and online instruction is as effective as face-to-face or brick-and-mortar instruction; although that often has more to do with who is enrolled in the online learning than the effectiveness of that modality (see pages 525-528 of Barbour [2019a] for a good summary of this issue and these findings). From the jurisdictions that utilized the more centralized model, Barbour and Mulcahy (2008) found that rural students enrolled in the Centre for Distance Learning and Innovation (CDLI) performed as well or better than any of their classroom or urban counterparts in their final course scores during the program’s first three years of operation. Similarly, the authors also reported that e-learning students performed as well as any other group of students in their grade twelve public examination results. More recently, data from the Newfoundland and Labrador English School District from the 2017-18 school year showed that students enrolled in CDLI courses had a successful completion rate of 86.8%, as compared to 80.9% for students enrolled in those same courses not in CDLI (i.e., in the traditional classroom environment). Similarly, Martell Consulting Services Ltd (2014) examined data from the first and second semesters of the 2013-14 school year and reported that teacher feedback indicated that online student achievement for students with a strong academic background was on par with or higher than classroom student achievement. Additionally, the authors found that during the first semester students in the centralized Nova Scotia Virtual School had a pass rate of 77% of students, while the second semester courses had a pass rate of 85% of students, which were also said to be consistent with classroom student achievement. These studies indicated that students can be successful in a centralized organizational model.

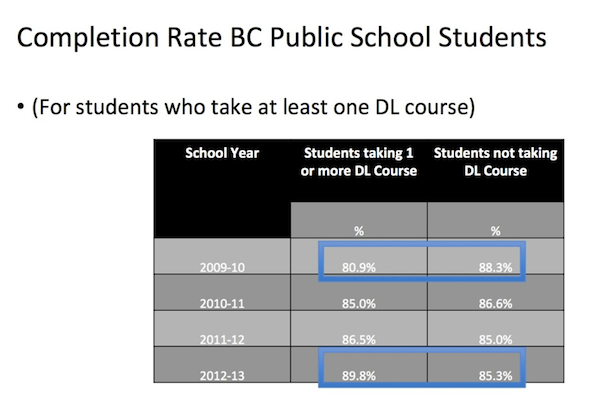

Prior to the introduction of the CDLI, several school districts in Newfoundland and Labrador maintained an online Advanced Placement (AP) program. Barbour and Mulcahy (2006) examined student performance in these online programs and found that online students performed as well or better on the AP exam than their classroom-based counterparts. In the highly decentralized province of British Columbia, a Ministry of Education presentation reported on the course completion rate of students in that province based on whether they completed a distributed learning (i.e., e-learning) course.

Figure 3. Completion rate for distributed learning (or online learning) students

taken from a presentation given by the British Columbia Ministry of Education (2014).

As Figure 3 indicates, during the 2009-10 school year there was a 7.4% difference between the completion rate of students that had taken one or more e-learning courses compared to students that did not take any e-learning courses. However, by the 2010-11 and 2011-12 school years the completion rates were approximately the same, and during the 2012-13 school year students that had taken one or more e-learning courses had a higher completion rate than the students that did not take any e-learning courses. This data indicates that students could also be successful in a decentralized organizational model.

In terms of data specific to the Ontario context, there is even less research available. It was reported in the 2010 State of the Nation: K-12 Online Learning in Canada report the Consortium d’apprentissage virtuel de langue française de l’Ontario had only a 4% failure rate during the 2009-10 school year (Barbour, 2010). Data collected by this CANeLearn-partnered project also found that the Ontario eLearning Consortium consistently reported a 90%+ completion rate. These data indicate that students can also be successful in an organizational model that is resourced centrally but operated in a decentralized manner.

Before we conclude the discussion, it is important to point out that the research comparing student performance based on the medium of instruction is fundamentally flawed. In his seminal article, Clark (1983) wrote that the different mediums “are mere vehicles that deliver instruction but do not influence student achievement any more than the truck that delivers our groceries causes changes in our nutrition” (p. 445). This view was not novel at the time (Glaser & Cooley, 1973; Levie & Dickie, 1973; Lumsdaine, 1963; Mielke, 1968; Schramm; 1977), and has long been the dominant view in the field of education and technology (Abdullahi, Ransom, & Kardam, 2014; DeLozier & Rhodes, 2017; Mayer, 1997; Oblinger & Hawkins, 2006; Patchan, Schunn, Sieg, & McLaughlin, 2016; Pedró, 2018; Reeves, 1999; Rey 2010; Ross, Morrison, & Lowther, 2010) — although none have coined as appropriate an analogy as the delivery truck.

To put it another way, researchers are constantly asked does e-learning work, whereas the better question is under what conditions can e-learning work? The implication of this reframing of the question is all students can learn effectively in any setting (Ferdig & Kennedy, 2014). This statement does not mean that every student could have success in the specific model of e-learning currently employed by programs in Ontario, in much the same way that not all students are having success in a specific model of classroom learning. What works for one student or one group of students may not work for others — regardless of setting or context. The real challenge for any educational program is how to design, deliver, and support learning opportunities in a way that can be effective for each student, which will look different for various populations of students.

There are actually two issues related to the proposed e-learning graduation requirement. The first issue is the ability of the government to scale the current system up to the levels needed to be able to serve all secondary students. The second issue is whether all students can have success in an e-learning environment. Each of these issues will be explored in the subsequent sub-sections.

Scalability. A four-course e-learning graduation requirement would be four times that of any online learning graduation requirement in North America (People for Education, 2019). During the 2017-18 school year, there were approximately 630,000 public secondary school students in the province (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2019b). As mentioned earlier, the People for Education’s Connecting to Success: Technology in Ontario Schools report found that approximately 5% or 31,500 secondary school students were enrolled in one or more e-learning courses in Ontario (Kapoor, 2019), while if the 65,000 students reported by the annual State of the Nation: K-12 e-Learning in Canada represented only secondary school students it would mean that approximately 10% were engaged in e-learning courses (Barbour & LaBonte, 2018). If those students were evenly distributed across the four grade levels of secondary school (i.e., grades 9-12), that would mean that there were approximately 8,000 to 16,000 students currently enrolled in e-learning in each secondary grade.

If the e-learning graduation requirement was implemented in phases, for e-learning enrollment it would mean:

This growth represents a significant increase in the number of students engaged in e-learning. For example, in the first year there would be three to four times the number of e-learning students. By the second year, there would be more students engaged in e-learning in Ontario than have ever been engaged in e-learning during a single school year in all of Canada. By the fourth year, three out of every four students engaged in e-learning in Canada would be from Ontario. Again, this growth represents a significant increase in the number of students engaged in e-learning. In order to implement a four-course e-learning requirement, the Government would have to scale the existing system by more than 10 times.

In order to scale the existing system to this level, the Government of Ontario would need to invest in significant, additional resources and professional development to ensure that students had the opportunity for success in order to maintain the existing ~80% graduation rate (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2019c). One area where investment would need to be made would be ensuring that students have equal access to their e-learning outside of the traditional school building and school hours, as well as providing a much higher level of technical support to parents and the home. For example, there was an image being circulated on social media that claimed a significant number of students in Ontario lacked access to a computer in the home and that large portions of the province lacked reliable Internet coverage.iv However, it is also important to note that the information in the image was sourced as Communications Monitoring Report 2017: Canada’s Communication System: An Overview for Canadians, a report that relied upon data from the 2011 census and an additional round of data collection in 2015 (Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission [CRTC], 2017). As such, the report would not have included advancements made by infrastructure initiatives such as:

In fact, an analysis by the Northern Policy Institute found that the Internet access situation in Northern Ontario was much better than the CRTC report or the infographic suggested (Masse, 2016).

Further, the Government of Ontario even included broadband access as a part of its Education that Works for You – Modernizing Classrooms announcement:

Technology (Broadband)

Digital skills are essential for everyone to be able to safely and effectively use technology. These skills are also needed as students advance in their education journey, and eventually enter the workplace. Broadband is foundational for supporting modernized digital learning in the classroom.

That is why all Ontario students and educators will have access to reliable, fast, secure and affordable internet services at school at a speed of one megabit per-second for every student in all regions of the province. The project will be completed by 2021-22, and will include all boards, schools and students.

This will give students access to technology that will better develop their digital skills and will provide quality broadband service for students in rural and northern communities.

To complete this project, the needs of each school will be individually assessed and then individual technical solutions will be implemented. Broadband expansion is underway at a majority of northern and rural schools. Already 32 per cent of northern schools have completed their upgrades, and 35 per cent of rural schools have been completed.

This strategy and vision was developed by the Ministry of Education, and follows a broader government vision for broadband expansion across the province.This infrastructure will support enhanced e-learning opportunities and access for students to the ministry’s Virtual Learning Environment wherever educational resources are available. (Government of Ontario, 2019b, pp. 3-9)

In fact, this section preceded the e-learning section in the Education that Works for You – Modernizing Classrooms announcement. Although, it is important to point out that the proposed timeline for implementation of the e-learning graduation requirement is the 2020-21 school year, while the proposed completion of the broadband project is not until 2021-22.

It is also important to note that e-learning projects have historically led to increased connectivity and broadband, as well as the deployment of technology. For example, Barry (2013) described how the announced CDLI program by the government of the day in Newfoundland and Labrador led to the necessary connectivity and technology being put in place in order to achieve the goals of that policy or implement those projects. This was also consistent with Barbour’s (2005) description of a variety of distance learning initiatives that had been previously implemented in Newfoundland and Labrador (up to the implementation of the CDLI). This experience is similar to that of Contact North, an Ontario-based organization that strived to provide educational opportunities for post-secondary and K-12 students in rural and remote areas of Ontario, who produced a report examining the ability of their educational projects to increase connectivity and technology throughout the province (Paul, 2012).

While not necessarily connected to the education announcement, in July the Government of Ontario announced investment in rural broadband (outside of the educational context) (Government of Ontario, 2019c), as well as the federal Government making a similar announcement (Blatchford, 2019). These announced initiatives do not necessarily mean that the required connectivity and technology will actually be deployed in time and at a level required to meet the challenges of scaling the current e-learning system to meet the demands of the current proposal. However, if e-learning is no longer a choice for students, these are necessary steps the government will need to undertake to ensure that students have equal access to their e-learning outside of the traditional school building and school hours.

Ability of e-learning to serve all students. One of the most frequently referenced opponents of the proposed e-learning changes in the popular media has been Farhadi (2019b), who — based on her dissertation study of 20 e-learning students in the Toronto District School Board — has argued that e-learning may not be appropriate for all students. However, the research indicates otherwise. For example, Ferdig (2009) undertook an evaluation of a Michigan-based e-learning program that had a student population that was described in this manner:

The 27 students who enrolled in the program included 15 male students and 12 female students. 21 of the students had dropped out and 6 had been expelled for selling drugs (4), possession of drugs (1), or being a threat to the teacher (1). They came from 6 different districts, with the largest participation coming from the home RESA district (12). Students who attended where anywhere between 1 and 21 credits short of graduation, with an average of 13 credits required. Most had been referred to the RESA by their parent, although they had also come on their own (2) or had been recommended by a probation officer (1), mental health counselor (2), or family member (2). There were multiple reasons these students left school, including boredom, anxiety, drugs, fighting, and mental health issues. (p. 5)

These 27 students would be defined as being at-risk of dropping out of the K-12 system under any circumstances. Yet the leadership of this particular e-learning program focused the design of the content, the delivery of instruction, and the support provided to students on the specific needs of this specific population of students. In the end, the study found that “students who struggled to the point of expulsion or dropping out of traditional school [were] enrolling, completing, and passing online classes. Even if only one of these students had succeeded, we would have had a significant outcome by changing the life of one individual. However, every single one of the 27 students passed at least one class in their time at the RESA’s [e-learning school]” (pp. 10-11). Ferdig later concluded that “students who are considered at-risk, including those who have dropped out, been expelled, or who have health problems, can succeed in online K-12 learning, given learning contexts and support personnel that meet their individual needs” (p. 23).

In another example of an e-learning program that focused on the conditions needed in order for a specific population to have success is the Odyssey Charter School, which was described in an earlier research study as:

Odyssey Charter School (OCS), based in Las Vegas Nevada, began in 1999 as a sponsored online charter school of the Clark County School District. It encompasses an elementary school and a high school. According to Watson et al (2008), from the Summer 2007 to the Summer 2008 OCS was responsible for 1405 full-time enrollments – with all of their students being full-time students. The elementary school was responsible for approximately half of these enrollments, while the high school made up the remaining half.

OCHS uses a blended learning model, with students physically attending the school one day a week for four hours (i.e., usually one morning or one afternoon) for a face-to-face course and the remainder of their courses are taught online. For two hours of this face-to-face time, students complete a core values course offered in a more traditional, direct instruction approach. The remaining two hours students meet with their mentor teachers to organize their coursework, check their progress, and address their academic needs. Pupils spend the four hours in one room with the same 10-20 students, while the teachers circulate from group to group visiting with students.

The faculty work on campus full-time and, in addition to their online teaching course loads, were responsible for mentoring approximately ninety students. Teachers regularly met their students by seeking them out during the four hours that the student is physically present in the school. However, some teachers simply were not able to interact with all of their students during this face-to-face time. This limitation, and the fact that students often only interacted with 10-20 students they physically attended school with each week; the OCHS began experimenting with social networking to increase the interaction between teachers and students and, especially, amongst students themselves. (Barbour & Plough, 2009, p. 57)

Both Odyssey Charter School and the Michigan-based RESA’s e-learning programs were specifically designed to ensure that the given population of students that they were created to serve had the necessary conditions in order to have success.

This is not to suggest that e-learning can easily and inherently serve all students. For example, in a US-based study of African American and Hispanic students enrolled in an e-learning program, researchers found:

However, the authors also noted that these challenges were consistent with the experience of this population of students in the brick-and-mortar or face-to-face environment. So, while it is true that not every student could have success in the specific way that the e-learning program in Ontario is currently implemented, if teachers, schools, school boards, and the Ministry of Education were to focus the design, delivery, and support of e-learning in Ontario on the specific needs of different populations of students, then all students could have success.The results showed that collaborative learning activities, access to resources, time convenience, student-teacher interactions, student-student interactions, improved academic behavior, and parental support helped to enhance online learning experiences and academic self-concept of the minority students. On the contrary, the lack of social presence, and the lack of cultural inclusion in course content constrain online learning experiences and academic self-concept of the students. The findings revealed some similarities between factors that influence minority students learning experiences online, and in face-to-face setting. The study also highlighted the need for teachers of online courses to understand the cultural backgrounds of minority students, and to use their knowledge to improve the learning experiences and academic self-concept of these students. (Kumi–Yeboah, Dogbey, & Yuan, 2017, p. 1)

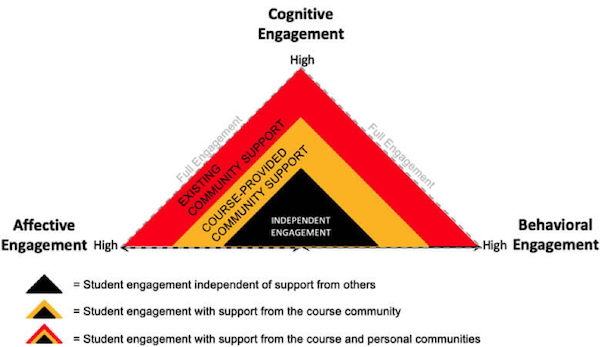

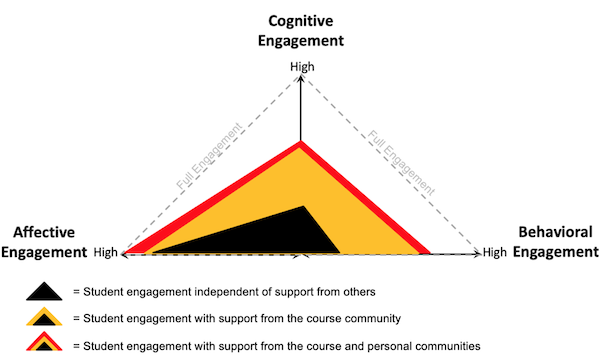

As Ferdig (2010) wrote, “simply replicating existing face-to-face environments often replicates the negative behavioral, affective, and cognitive outcomes of at-risk students” (p. iii). However, if e-learning environments are designed, delivered, and supported in a manner that accounts for the needs of at-risk students — as they were in the Odyssey Charter School and the Michigan-based RESA’s e-learning programs — students can succeed. Further, both the Ministry of Education requirements for e-learning and the actual model of e-learning that most programs in Ontario have implemented is focused on providing students with every opportunity to have success. In order to be successful in any educational setting, students need to engage in an affective, behaviour, and cognitive manner.

Figure 4. Every student enters any educational setting with certain individual characteristics in these three areas (i.e., the black area). Between a student’s community, their family, and their school, there are supports that already exist to help the student achieve full engagement in their learning (i.e., the red area). (Borup, Graham, & Archambault, 2019)

The goal of the e-learning program, then, is to provide the necessary supports to make up the difference between what the student already possesses and is able to gain from their existing community and the level of engagement that is needed for the student to be successful. For example, if a student or group of students enrolled in the e-learning program had an inherently high level of affective engagement but low levels of cognitive engagement and behavioral engagement (see Figure 5), then the likelihood of success for all students would be limited.

Figure 5. Every student enters any educational setting with certain individual characteristics in these three areas (i.e., the black area). Between a student’s community, their family, and their school, there are supports that already exist to help the student achieve full engagement in their learning (i.e., the red area). (Borup, Graham, & Archambault, 2019)

If the community that existed within the e-learning community (i.e., the golden course community portion) was sufficient to mitigate only a portion of the missing cognitive engagement and behavioral engagement, and the student’s personal community had little impact on either variable, the student would not be fully engaged in their e-learning course and the likelihood of success would be challenged. Either the e-learning program itself or the student’s local school would need to adjust the way in which the e-learning course was designed, the manner in which the course was delivered or additional online and/or local supports would need to be provided to be able to address the missing white portion in Figure 5 in order for the student to reach full engagement and have an equitable opportunity to have success in their e-learning course. The nature of those changes to the design, delivery, and support must differ based on the specific needs of different populations of students. Well-designed and implemented e-learning programs seek to provide and adjust those supports.

This success can be found in other jurisdictions that have implemented their own e-learning graduation requirements. While no other Canadian jurisdiction has any form of requirement, there are six US states that have some form of online or e-learning graduation requirement:

While there are many differences in the ways K-12 education is governed, managed, funded, staffed, delivered, and measured — notwithstanding the significant differences in the basic nature of the curriculum, as the United States has the only other jurisdictions with some form of online learning graduation requirement — it is important to consider the impact the requirement has had on graduation metrics.

In examining the graduation data for some of these jurisdictions, the Michigan Department of Education reported a four-year graduation rate of 74.33% in 2011 (i.e., the first class that would have been held to the online learning graduation requirement), which was a decrease of 1.62% from the previous year. v However, there was also an increase in the graduation rate each subsequent year since the requirement was implemented. Similarly, the Alabama Department of Education reported that the graduation rate in 2013 (i.e., the first class that would have been held to the online learning graduation requirement) was 80% or five percent higher than the previous year; and their graduation rate had also climbed each year since the online learning graduation requirement has been implemented.

Readers should be cautioned, however, with regards to assuming that the introduction of an online or e-learning graduation requirement was the only factor impacting graduation rates. Since 2000, the No Child Left Behind Act and its predecessor, the Every Student Succeeds Act, both placed a major emphasis on raising graduation rates in the United States. As such, graduation rates have been going up consistently but other measures of achievement have not risen. This dichotomy suggests that graduation rates may have been inflated in some way that do not truly represent student academic success, as was reported in the case of Alabama (Carsen, 2016). The main takeaway from examining this information is that, based on the available data, it does not appear that the implementation of an online or e-learning graduation requirement has negatively impacted graduation rates in these other jurisdictions.

The proposal to implement a class size limitation of 35 students in e-learning classes, a figure that is 25% more than classroom-based courses, is based on the premise that a single teacher can effectively facilitate learning for more e-learning students with the same amount of effort. Put another way, 28 classroom-based students create the same amount of work or load for the teacher as 35 e-learning students — or that teaching in an e-learning environment is 80% of the work of teaching in a classroom-based context.

From a strict e-learning, class-size perspective, a part of Barbour’s (2019b) examination of provisions for the working conditions of K-12 e-learning teachers in Canada based on collective agreements included contract language related to e-learning class size. In fact, four of the five contract language samples provided by the Ontario Secondary School Teachers Federation for that study included statements that e-learning courses must follow the class size limits for face-to-face courses. For example, in one letter of understanding it is stated “for the life of the 2008-2012 collective agreement E-Learning courses will comply with class size maximums” (p. 18), while another stated that “all electronically-delivered courses will be subject to the class size maxima as outlined in Article X of the Collective Agreement” (p. 20). Similarly, an article in one collective agreement stated that “e-learning courses for secondary school students shall be subject to the same class size restriction as other classes in secondary schools” (p. 20). These samples were consistent with an earlier vignette provided by the Ontario Secondary Schools Teachers Federation, District 12, Secondary Teachers Bargaining Unit that appeared in the 2013 edition of the annual State of the Nation: K-12 e-Learning in Canada report (Barbour, 2013). According to that vignette, the local bargaining unit gained the protection for e-learning teachers that the “class size limits that apply to traditional classes will also apply to e-learning classes” (p. 52).

Another jurisdiction where the class size limit for e-learning courses has been included in the collective agreement between the government and the teacher's union is Nova Scotia. In a section devoted specifically to e-learning, it stated:

49.08 The maximum number of students permitted in a distributed learning course shall be twenty five (25). (Government of Nova Scotia, 2017, p. 61)

It should be noted that this maximum e-learning class size represents 10 fewer students than is being proposed in Ontario. Interestingly, the previous version of this clause from the collective agreement stated that:

49.06 – (i) Where existing video and audio transmission technologies are being utilized for distance education in schools, the maximum number of students enrolled in a distance education course at all sites should not exceed twenty-two (22) students, unless the School Board can demonstrate to the Union the feasibility of increasing the number to a maximum number of twenty-five (25) students. The maximum number of sites shall not exceed five (5).

(ii) In the event new technologies are used in the delivery of distance education courses, the parties agree to meet to determine the appropriate number of sites, student numbers, and other related educational issues. (Government of Nova Scotia, 2010, p. 58)

As a part of their analysis of the various e-learning clauses contained in the collective agreement at the time, Barbour and Adelstein (2013) wrote that this particular clause:

… puts a soft cap of 22 and a hard cap of 25 students on all sites. The nature of distance learning requires teachers to interact with students, often more frequently than in the face-to-face environment to ensure student understanding. In a traditional classroom a 12 teacher has access to additional information, such as visual cues, to gauge student learning. Many of these cues are not available to the [e-learning] teacher. By limiting the class size to 22, the instructor has a better chance of conferencing with each distance learner individually. (p. 30)

While not specifically mentioned by the authors, this earlier clause also limited the number of sites or schools that could be represented among those 22-25 students to five. This limitation also recognized the workload that can be placed on teachers with having to deal with facilitators/mentors, technology support, and local school administrators at multiple school sites.

Similarly, as a part of the collective agreement between the Calgary School Board and the Alberta Teachers Association there was special consideration given to the fact that the nature of ‘teaching’ for e-learning teachers was different than for face-to-face teachers and, as such, required a different formula to determine student load. For e-learning teachers in the Calgary board’s CBe-Learn program, it was determined that:

One (1) Full Time Equivalent (FTE) assignment for instructional and assignable time for teachers in CBe Learn is 585 student credits, determined by multiplying the number of active students by the number of course credits. If the number of courses multiplied by the course credit weight exceeds 20 (i.e., 4 courses x 5 credits each), consideration will be given to reducing the number of students. A teacher in CBe Learn may agree to other configurations based on credit value of the courses and determined by shared decision making as per the Staff Involvement in School Decisions document. A maximum of six hours per week may be assigned to non-instructional tasks such as curriculum development, staff meetings, and other district assigned in-service. This provision does not apply to teachers in a regular classroom setting. The parties shall jointly review the operation of this clause and report back to their respective parties by Dec 31, 2015. (Alberta Teachers Association, 2012, ¶ Letter of Understanding – CBe Learn Teachers)

The math involved in the provision roughly translates to 117 students per full-time equivalent respectively. In addition to setting a maximum student load, the article also establishes maximum amounts of time that the school board as employer can expect the teacher to spend on tasks often assigned to other roles of the e-learning teachers (e.g., online course development). It should be noted the research examining the impact of class size on e-learning student performance has consistently found when the e-learning class size increases, it has a negative impact on student performance in comparison to their face-to-face counterparts (Gill et al., 2015; Miron & Gulosino, 2016; Miron, Shank, & Davidson, 2018; Miron & Urschel, 2012; Molnar et al., 2013, 2014, 2015, 2017, 2019; Woodworth et al., 2015).

Finally, it is important to point out that the contract language in these collective agreements focused solely on the role of the e-learning teacher (i.e., the professional responsibility for overseeing the delivery of the e-learning course), and did not factor in the other educational professionals involved in the e-learning environment (such as the role of the school-based facilitator or mentor described above). The language described above does not consider the supporting roles required of teachers for the evaluation and selection of resources, design of instructional activities, actual instruction, social/emotional support, support for the use of technology, and — finally — assessment. These responsibilities are often shared among several educators and, in some cases, assessment is built into course design and facilitated by the technology, while in the regular school classroom (i.e., face-to-face) these roles are often the sole responsibility of a single teacher. However, the educators that perform these roles in the e-learning environment — at least based on the e-Learning Ontario’s Master User Agreement — are required to be present in the province’s e-learning system. Additionally, as the local facilitator/mentor role has a significant impact on potential e-learning student success, those individuals should be factored into any conversation around e-learning class size.

As you might imagine, the 15 March 2019 education announcement by the Government of Ontario sparked considerable discussion and debate in both main-stream and social media channels. Unfortunately, a lot of the commentary — at least with respect to the proposed e-learning changes — included many discredited myths, misinformation, and pitted e-learning against classroom-based learning. There have also been some that have extrapolated motives and speculated future government actions – such as expanding the influence of corporations and private interests in public school e-learning (Farhadi, 2019a) — even though there is no evidence thus far of any of this speculation. In this article we have attempted to explore the current state of e-learning in Ontario and examine what is actually known about the e-learning aspects of the Education that Works for You — Modernizing Classrooms through the lens of existing research and literature.

The Ontario e-Learning Strategy has provided a regulatory overview for the system of e-learning since 2006. In the existing system, the Ministry of Education “provides school boards with access to a learning management system and other tools for the delivery of e-learning, asynchronous course content and a variety of multimedia learning objects, and a variety of other technical and human resource supports” (Barbour & LaBonte, 2017, p. 25). While the existing model of e-learning includes highly centralized components, it also features a decentralized model of delivery by individual e-learning programs. Each school board can offer an e-learning program, and most have also chosen to participate in one or more consortia designed to allow its school board members to work together to maximize their online offerings by sharing course offerings, resources and students. However, even within the decentralized delivery model the Ministry mandates local supporting teachers at each school setting where students are taking e-learning courses. As well, the Ministry funds one educator per school board to support technology-enabled learning and provides the resources, courses, and tools to teach in the online environment (i.e., the “Technology Enabled Learning and Teaching Contact”).

First, there is some confusion concerning the proposal to create a centralized system of e-learning, given the nature of the current system. According to the annual State of the Nation: K-12 e-Learning in Canada reports (Barbour, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013; Barbour & LaBonte, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018; Barbour & Stewart, 2008), across Canada the less populated jurisdictions tend to utilize a centralized model of e-learning, with most of the other jurisdictions have a more decentralized model. While the research is limited, however, there appears to be little difference in student outcomes based on whether the provincial/territorial model of e-learning is centralized or decentralized — as both appear to achieve outcomes comparable to face-to-face contexts.

Second, until the details for implementation of the online learning graduation mandate are clear, it is difficult to speculate on the impact of the announcement. However, the government’s announcement of four graduation credits required to be via e-learning amidst per-student funding reductions that boards of education will receive in the next school year could create serious challenges for maintaining the level of quality instruction currently provided through Ontario’s e-learning programs. The current research does suggest that the scalability challenge is huge and likely to impact quality without significant resourcing. Additionally, it must be underscored that all students can be successful in an e-learning environment, so scholars should work to dispel the notion that e-learning is inferior to classroom learning. It is simply another learning environment teachers can leverage to support and engage students — just as a makerspace, a library, a metal or wood shop, or any other place where teachers can structure and manage learning opportunities. Structure, support, and teacher presence are the critical ingredients for success in any learning environment, and e-learning is not excluded from this. In order to scale the types of supports that are necessary in order to allow the conditions that allow all students to have success will also require significant resources.

Third, the literature related to e-learning class size in Canada underscores the challenge of which teachers involved in a student’s e-learning are counted and how they are counted. While class-size limits have been set in many jurisdictions in Canada, they typically follow the same classroom limits, or at least are based on them. Additionally, the e-learning class-size limits generally do not include the educators involved in the design of the e-learning course content or the local support provided to e-learning students. Yet, the e-Learning Ontario Master User Agreement specifies that local support must be in place for any e-learning. Further, the research has shown a clear connection between increases in e-learning class size and a negative impact on student outcomes.

Finally, the traditional model of distance education delivery (often referred to as the legacy model) — which consisted of content delivery, assignment completion, and information recall testing — lacked success. It relied on a centralized teacher with remote students accessing online courses, typically on their own without local support. Legacy distance education models had course completion rates that on average ranged from a high of ~70% and a low of 50% (Winkelmans, Anderson, & Barbour, 2010), with some programs reporting rates as low as 20% (Sweet, 1991). Ontario’s existing model has local support and access to courses with completion rates comparable to or better than classroom-based courses (up to 94% completion in some consortium models). Most distance learning programs in Canada have shifted away from a legacy model to community-based programs with active local technology and learning support for students. Successful e-learning models favour a reallocation of resources and funding, not a reduction. The concern we have is that should the Ontario government’s e-learning course requirement implementation plan rely on earlier models of distance education, the quality and success of e-learning in the province could well be undermined.

Abdullahi, S., Ransom, E. N., & Kardam, M. S. (2014). The significant of internet technology to education and students in acquiring quality education. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 32, 145-153.

Alberta Teachers Association. (2012). 2012-2016 collective agreement between the Board of Trustees of the Calgary Board of Education and the Alberta Teachers’ Association. Edmonton, AB: Author. Retrieved from https://local38.teachers.ab.ca/About%20the%20Local/Salaries%20and%20Benefits/Pages/2012-16CollAgg.aspx

Barbour, M. K. (2005). From telematics to web-based: The progression of distance education in Newfoundland and Labrador. British Journal of Educational Technology, 36(6), 1055-1058.

Barbour, M. K. (2009). State of the nation: K-12 online learning in Canada. Vienna, VA: International Council for K-12 Online Learning. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/StateOfTheNation2009.pdf

Barbour, M. K. (2010). State of the nation study: K-12 online learning in Canada. Vienna, VA: International Council for K-12 Online Learning. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/StateOfTheNation2010.pdf

Barbour, M. K. (2011). State of the nation: K-12 online learning in Canada. Vienna, VA: International Council for K-12 Online Learning. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/StateOfTheNation2011.pdf

Barbour, M. K. (2012). State of the nation: K-12 online learning in Canada. Victoria, BC/Vienna, VA: Open School BC/International Council for K-12 Online Learning. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/StateOfTheNation2012.pdf

Barbour, M. K. (2013). State of the nation: K-12 online learning in Canada. Victoria, BC: Open School BC. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/StateOfTheNation2013.pdf

Barbour, M. K. (2019a). The landscape of K-12 online learning: Examining the state of the field. In M. G. Moore & W. C. Diehl (Eds.), Handbook of distance education (4th ed.) (pp. 521-542). New York: Routledge.

Barbour, M. K. (2019b). E-learning class size. Half Moon Bay, BC: Canadian E-Learning Network. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/e-learning-class-size.pdf

Barbour, M. K., & Adelstein, D. (2013). Voracious appetite of online teaching: Examining labour issues related to K-12 online learning. Vancouver, BC: British Columbia Teachers Federation. Retrieved from https://www.bctf.ca/uploadedFiles/Public/Issues/Technology/VoraciousAppetite.pdf

Barbour, M. K., & LaBonte, R. (2014). Abbreviated state of the nation: K-12 online learning in Canada. Cobble Hill, BC: Canadian E-Learning Network. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/StateOfTheNation2014.pdf

Barbour, M. K., & LaBonte, R. (2015). Abbreviated State of the nation: K-12 e-learning in Canada. Cobble Hill, BC: Canadian E-Learning Network. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/StateOfTheNation2015.pdf

Barbour, M. K., & LaBonte, R. (2016). State of the nation: K-12 e-learning in Canada. Cobble Hill, BC: Canadian E-Learning Network. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/StateNation16.pdf

Barbour, M. K., & LaBonte, R. (2017). State of the nation: K-12 e-learning in Canada. Cobble Hill, BC: Canadian E-Learning Network. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/StateNation17.pdf

Barbour, M. K., & LaBonte, R. (2018). State of the nation study: K-12 e-learning in Canada. Half Moon Bay, BC: Canadian E-Learning Network. Retrieved from https://k12sotn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/StateNation18.pdf

Barbour, M. K., & Mulcahy, D. (2004). The role of mediating teachers in Newfoundland ‘s new model of distance education. The Morning Watch, 32(1). Retrieved from http://www.mun.ca/educ/faculty/mwatch/fall4/barbourmulcahy.htm

Barbour, M. K., & Mulcahy, D. (2006). An inquiry into retention and achievement differences in campus based and web based AP courses. Rural Educator, 27(3), 8-12.

Barbour, M. K., & Mulcahy, D. (2008). How are they doing? Examining student achievement in virtual schooling. Education in Rural Australia, 18(2), 63-74.

Barbour, M. K. & Plough, C. (2009). Social networking in cyberschooling: Helping to make online learning less isolating. Tech Trends, 53(4), 56-60.

Barbour, M. K., & Stewart, R. (2008). A snapshot state of the nation study: K-12 online learning in Canada. Vienna, VA: North American Council for Online Learning. Retrieved from http://www.inacol.org/resource/state-of-the-nation-k-12-online-learning-in-canada-2008/

Barker, K., & Wendel, T. (2001). e-Learning: Studying Canada’s virtual secondary schools. Kelowna, BC: Society for the Advancement of Excellence in Education. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20040720185017/http://www.saee.ca/pdfs/006.pdf

Barker, K., Wendel, T., & Richmond, M. (1999). Linking the literature: School effectiveness and virtual schools. Vancouver, BC: FuturEd. Retrieved from http://web.archive.org/web/20061112102653/http://www.futured.com/pdf/Virtual.pdf

Barry, M. (2013, February 18-March 20). Rendering distance transparent: K-12 distance ed. in NL, CA. Not banjaxed…Yet: Give it time. Retrieved from https://mauriceabarry.wordpress.com/rendering-distance-transparent-k-12-distance-ed-in-nl-ca/

Blatchford, A. (2019, July 23). Canada to invest in satellite technology to connect rural, remote areas: Satellites will provide high-speed connectivity in rural, remote communities around the globe. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/satellite-high-speed-internet-1.5222655

Borup, J., Chambers, C. B. & Stimson, R. (2018). Helping online students be successful: Student perceptions of online teacher and on-site mentor facilitation support. Lansing, MI: Michigan Virtual University. Retrieved from https://mvlri.org/research/publications/helping-online-students-be-successful-student-perceptions-of-support/

Borup, J., Graham, C. R., & Archambault, L. (2019, March). Revisiting the adolescent community of engagement framework. A roundtable presentation at annual conference for the Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education, Las Vegas, NV.

British Columbia Ministry of Education. (2014). Completion rate BC public schools. A presentation at the Digital Learning Symposium, Vancouver, BC.

Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission. (2017). Communications monitoring report 2017: Canada’s communication system: An overview for Canadians. Ottawa, ON: Author. Retrieved from https://crtc.gc.ca/eng/publications/reports/policymonitoring/2017/cmr.htm

Carsen, D. (2016, December 19). Alabama admits its high school graduation rate was inflated. National Public Radio. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/sections/ed/2016/12/19/505729524/alabama-admits-its-high-school-graduation-rate-was-inflated

Clark, R. E. (1983). Reconsidering research on learning from media. Review of Educational Research, 53(4), 445-459.

Davis, N., & Niederhauser, D. S. (2007). Virtual schooling. Learning & Leading with Technology, 34(7), 10-15. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ779830.pdf

DeLozier, S. J., & Rhodes, M. G. (2017). Flipped classrooms: A review of key ideas and recommendations for practice. Educational Psychology Review, 29(1), 141-151.

Durkacz, K. (2019, April 2). Ford cuts attack students and education. The Hamilton Spectator. Retrieved from https://www.thespec.com/opinion-story/9263128-ford-cuts-attack-students-and-education/

Farhadi, B (2019a, October 17). In Doug Ford’s e-learning gamble, high school students will lose. The Conversation. Retrieved from https://theconversation.com/in-doug-fords-e-learning-gamble-high-school-students-will-lose-122826

Farhadi, B. (2019, April 8). A Summary of findings. Retrieved from https://beyhanfarhadi.com/2019/04/08/summary-of-findings/

Ferdig, R. E. (2009). K-12 online learning and the retention of at-risk students. Port Huron, MI: St. Clair County Regional Education Services Agency.

Ferdig, R. E. (2010). Understanding the role and applicability of K-12 online learning to support student dropout recovery efforts. Lansing, MI: Michigan Virtual University. Retrieved from https://mvlri.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/DropoutRecoveryEfforts.pdf

Ferdig, R. E., Cavanaugh, C., DiPietro, M., Black, E. W., & Dawson, K. (2009). Virtual schooling standards and best practices for teacher education. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 17(4), 479-503.

Ferdig, R., & Kennedy, K. (2014). Handbook of research on K-12 online and blended learning. Pittsburgh, PA: Entertainment Technology Center Press, Carnegie Mellon University. Retrieved from https://figshare.com/articles/Handbook_of_Research_on_K-12_Online_and_Blended_Learning/6686810

Gill, B., Walsh, L., Wulsin, C. S., Matulewicz, H., Severn, V., Grau, E., Lee, A., & Kerwin, T. (2015). Inside online charter schools. Cambridge, MA: Mathematica Policy Research. Retrieved from https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-andfindings/publications/inside-online-charter-schools

Glaser. R., & Cooley. W. W. (1973). Instrumentation for teaching and instructional management. In R. Travers (Ed.). Second handbook of research on teaching (pp. 834-856). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally College Publishing.

Government of Nova Scotia. (2010). Nova Scotia Minister of Education & The Nova Scotia Teachers Union: Provincial contract agreement. Halifax, NS: Authors. Retrieved from http://nstu.ca/images/pklot/TPA%202010-2012.pdf

Government of Nova Scotia. (2017). Agreement between the Minister of Education and Early Childhood Development of the Province of Nova Scotia and the Nova Scotia Teachers Union. Halifax, NS: Author. Retrieved from https://www.ednet.ns.ca/fr/docs/teachersprovincialagreement2015-2019.pdf

Government of Ontario. (2019a). News release – 'Back-to-basics' math curriculum, renewed focus on skilled trades and cellphone ban in the classroom coming soon to Ontario: Minister of Education Lisa Thompson unveils Government’s vision for ‘education that works for you.’ Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario. Retrieved from https://news.ontario.ca/edu/en/2019/03/back-to-basics-math-curriculum-renewed-focuson-skilled-trades-and-cellphone-ban-in-the-classroom-co.html

Government of Ontario. (2019b). Backgrounder – education that works for you – modernizing classrooms: Province modernizing classrooms. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario. Retrieved from https://news.ontario.ca/edu/en/2019/03/education-that-worksfor-you-2.html

Government of Ontario. (2019c). Ontario improving internet and cell phone service in rural and remote communities: Plan will connect up to 220,000 new homes and businesses. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario. Retrieved from https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2019/07/ontario-improving-internet-and-cell-phone-service-in-rural-and-remote-communities.html

Government of Ontario. (2019d). Ontario brings learning into the digital age: Province announces plan to enhance online learning, become global leader. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario. Retrieved from https://news.ontario.ca/edu/en/2019/11/ontario-brings-learning-into-the-digital-age.html

Graham, C. R. (2006). Chapter 1: Blended learning system: Definition, current trends, future directions. In C. J. Bonk & C. R. Graham (Eds.), Handbook of blended learning (pp. 3-21). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Jones, A. (2019, April, 8). Few Ontario students currently enrolled in e-learning courses: Report. Global News. Retrieved from https://globalnews.ca/news/5140569/ontario-students-elearning-courses/

Kapoor, A. (2019). Connecting to success: Technology in Ontario schools. Toronto, ON: People for Education. Retrieved from https://peopleforeducation.ca/our-work/connecting-to-success-technology-in-ontarios-schools/

Kennedy, K. (2018, September 25). Online learning graduation requirements. Durango, CO: Digital Learning Collaborative. Retrieved from https://www.digitallearningcollab.com/online-learning-graduation-requirements

Kumi–Yeboah, A., Dogbey, J., & Yuan, G. (2018). Exploring factors that promote online learning experiences and academic self-concept of minority high school students. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 50(1), 1-17.

Levie, W. H., & Dickie, K. (1973). The analysis and application of media. In R. Travers (Ed.), The second handbook of research on teaching (pp. 858-882). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Lumsdaine, A. (1963). Instruments and media of instruction. In N. Gage (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (pp. 583–682). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Martell Consulting Services Ltd. (2014). Evaluation findings on the Nova Scotia Virtual School: Final report. Tantallon, NS: Author.

Masse, M.-J. (2016). The digital divide: Internet access in Northern Ontario. Thunder Bay, ON: Northern Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.northernpolicy.ca/article/the-digital-divide-internet-access-in-northern-ontario-26289.asp

Mayer, R. E. (1997). Multimedia learning: Are we asking the right questions? Educational Psychologist, 32(1), 1-19.

Mielke, K. (1980). Commentary. Educational Communications and Technology Journal, 28(1), 66-69.

Miron, G. & Gulosino, C. (2016). Virtual schools report 2016: Directory and performance review. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/virtual-schools-annual-2016

Miron, G., & Shank, C., & Davidson, C. (2018). Full-time virtual and blended schools: Enrollment, student characteristics, and performance. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/virtual-schoolsannual-2018

Miron, G., & Urschel, J. L. (2012). Understanding and improving full-time virtual schools: A study of student characteristics, school finance, and school performance in schools operated by K12 Inc. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from https://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/understanding-improving-virtual

Molnar, A. (Ed.); Huerta, L., Shafer, S. R., Barbour, M. K., Miron, G., Gulosino, C. (2015). Virtual schools in the U.S. 2015: Politics, performance, policy, and research evidence. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/virtual-schools-annual-2015

Molnar, A., Miron, G., Elgeberi, N., Barbour, M. K., Huerta, L., Shafer, S. R., Rice, J. K. (2019). Virtual schools in the U.S. 2019. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/virtual-schools-annual-2019

Molnar, A., Miron, G., Gulosino, C., Shank, C., Davidson, C., Barbour, M. K., Huerta, L., Shafter, S. R., Rice, J. K., & Nitkin, D. (2017). Virtual schools report 2017. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/virtual-schools-annual-2017

Molnar, A. (Ed.); Miron, G., Huerta, L., Cuban, L., Horvitz, B., Gulosino, C., Rice, J. K., & Shafer, S. R. (2013). Virtual schools in the U.S. 2013: Politics, performance, policy, and research evidence. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/virtual-schools-annual-2013

Molnar, A. (Ed.); Rice, J. K., Huerta, L., Shafer, S. R., Barbour, M. K., Miron, G., Gulosino, C., Horvitz, B. (2014). Virtual schools in the U.S. 2014: Politics, performance, policy, and research evidence. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center. Retrieved from http://nepc.colorado.edu/publication/virtual-schools-annual-2014

Oblinger, D. G., & Hawkins, B. L. (2006). The myth about no significant difference. Educause Review, 41(6), 14-15.

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2013). Provincial e-learning strategy: Master user agreement. Toronto, ON: Author. Retrieved from https://efis.fma.csc.gov.on.ca/faab/Memos/B2019/B09_attach1_EN.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2019a). Class size consultation guide. Toronto, ON: Author. Retrieved from https://efis.fma.csc.gov.on.ca/faab/Memos/B2019/B09_attach1_EN.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2019b) Education facts, 2017-18 (Preliminary). Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/educationfacts.html

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2019c). Getting results. Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/gettingResultsGrad.html

Paikin, S. (2019, April 19). How to learn online: The Agenda with Steve Paikin. Television Ontario (TVO). Retrieved from https://www.tvo.org/video/how-to-learn-online

Patchan, M. M., Schunn, C. D., Sieg, W., & McLaughlin, D. (2016). The effect of blended instruction on accelerated learning. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 25(3), 269-286.

Paul, R. H. (2012). Contact North: A case study in public policy – Lessons from the first 25 years. Thunder Bay, ON: Contact North. Retrieved from https://teachonline.ca/sites/default/files/contactNorth/files/pdf/publications/cn_casestudy.pdf