Vol. 37, No. 1, 2022

https://doi.org/10.55667/ijede.2022.v37.i1.1219

Abstract: Distance learning is becoming increasingly prevalent. If education is a community affair, how do we digitally design the conditions for learning at a distance for our students? This research examines a distance learning environment within a Master’s Degree course created using online discussion forums, based upon the Community of Inquiry model (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000). A structural analysis of the discussion forums, a quantitative analysis of social, teaching, and cognitive presence using a ten-factor model (Dempsey & Zhang, 2019), and a qualitative analysis of individual interviews with community members, found that the role of the instructor is critical in providing metacognitive direction to the community. This direction includes encouraging students towards ‘cwelelep’, or the pursuit of uncertainty and cognitive dissonance, thus opening the way for the relational construction of knowledge. To help students embrace uncertainty, they require explicit metacognitive knowledge of the processes that allow a community of inquiry to function.

Keywords: distance education, community of inquiry, social construction, metacognition, First Nations principles

Résumé: L'apprentissage à distance est de plus en plus répandu. Si l'éducation est une affaire de communauté, comment pouvons-nous concevoir numériquement les conditions d'apprentissage à distance pour nos étudiants ? Cette recherche examine un environnement d'apprentissage à distance dans un cours de maîtrise créé en utilisant des forums de discussion en ligne, basé sur le modèle de la communauté d'enquête (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000). Une analyse structurelle des forums de discussion, une analyse quantitative de la présence sociale, pédagogique et cognitive à l'aide d'un modèle à dix facteurs (Dempsey & Zhang, 2019), ainsi qu'une analyse qualitative des entretiens individuels avec les membres de la communauté, ont révélé que le rôle de l'instructeur est essentiel pour fournir une orientation métacognitive à la communauté. Cette orientation consiste notamment à encourager les étudiants vers le "cwelelep", ou la poursuite de l'incertitude et de la dissonance cognitive, ouvrant ainsi la voie à la construction relationnelle des connaissances. Pour être prêts à accueillir l'incertitude, les étudiants ont besoin d’une connaissance métacognitive explicite des processus qui permettent à une communauté de recherche de fonctionner.

Mots-clés: enseignement à distance, communauté d'enquête, construction sociale, métacognition, principes des Premières nations

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

Distance learning is becoming increasingly prevalent for various reasons, including globalization and efforts by universities to attract more students. For example, between 2008/2009 and 2018/2019, the percentage of international students enrolled at Canadian universities and colleges increased by 210% (Statistics Canada, 2020). More broadly, UNESCO (UNESCOa, n.d.) notes that media such as mobile technologies has reached all areas of the globe, bringing access to education to a global audience.

As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, the International Commission on the Futures of Education has called for the protection of social spaces provided by schools, not only in the traditional, physical sense, but as a “space-time of collective living” (UNESCO, 2020) where students may assemble virtually with their instructors to create the conditions needed for knowledge construction.

As we — educators, institutions and students — broaden our expectations for distance formats, we must become more adept at creating the conditions needed for the construction of knowledge through these distance formats, allowing students to access their preferred programs of study, regardless of location. For example, the institution in which this research is conducted enrolls students from all over the world into its distance programs.

If education is a community affair, and if knowledge is constructed through interactions with others, how do we digitally design for our students, “the possibilities for the production or construction of knowledge”? (Freire, 1998, p. 30).

From a relational constructionist approach to education, we need to provide spaces where students and educators can share “alternative paths to knowledge” (Sanford et al., 2012, p. 20) that embrace complexity and context. We need to encourage students to adopt, from Indigenous ways of knowing, the principle of ‘cwelelep’, which is recognizing the need to sometimes be in a place of dissonance and uncertainty, so as to be open to new learning (Sanford et al., 2012, p. 24). We need to provide opportunities and spaces for our students to engage with each other and share perspectives in a manner that invites challenge and creates dissonance amongst their community.

We also need to provide spaces where students, as ‘knowledge keepers’ of their own perspectives, can share a sense of humility with their peers and witness each other’s transformation (Ravensbergen, 2019). Such spaces may be viewed as circles of life (Gergen, 2009) that allow us to expand our opportunities to encounter and interact with different ways of knowing. The more circles we have, the more extensive and complex our experience as we bring our learning from one circle to the next. This is echoed in the concept of ‘Etuaptmumk’ (Roher et al., 2021), or ‘two-eyed seeing’, in which we “weave back and forth between our worldviews” (Bartlett et al., 2012, p. 334). By willingly exposing ourselves to others’ world views of concepts that we are concurrently exploring, we give ourselves the opportunity to develop a wider, and more sophisticated world view that accepts others and their perspectives, even as they differ from our own.

By the careful formation of places where students can engage with each other, we also create space for students to experience that, “Learning involves recognizing the consequences of one’s actions” (First Nations Education Steering Committee, n.d., para 2). One consequence of engaging in dialogue and learning is that others might learn from you. This is a profound responsibility. By becoming aware of this responsibility, students also embrace the First Nations concept that learning is focused on “reciprocal relationships” (First Nations Education Steering Committee, n.d., para 2) with each other. Creating space for student engagement and the social construction of knowledge can be viewed as a central tenet of educational philosophy.

Many distance education courses including ‘Master’ level courses support only limited modes of communication for academic purposes among students, and between students and the instructor. One common mode is discussion forums, which allow for asynchronous interaction or ‘discussion’ between participants at a distance, both physically and temporally. To create the conditions that Freire (1998) tells us, as educators, are our responsibility to create, we need to ever broaden our ability to use these tools.

The purpose of this research is to investigate through a Community of Inquiry (COI) Model (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000) how a distance-learning course can engage students to share their experiences including their own cognitive dissonance with others.

The theoretical framework of this research is Social Construction, a movement from the social sciences that has become one of the most important and innovative paradigms of contemporary psychology (Hammack, 2018). Social construction focuses on the creation of realities through human interaction, and so looks at the role of context and perspective in producing localized and highly relevant knowledge (Gergen, 2015). If we embrace knowledge as co-created in relationship, context, and history, then education is not just a matter of content transmission, but also holds the possibility of creating new forms of knowledge.

Camargo-Borges and Moschetta, (2014) affirm that for students and instructors to connect to a learning community, they need to develop a sense of their ‘relational being’, acknowledging that others in their community contribute to their own knowledge, and are motivated by differences in understanding. They add that relational beings can be supported by “relational technologies” (p. 340). Discussion forums can serve as one form of relational technology.

This paper presents learning as a systematic and relational phenomenon (Gergen, 2009). If we understand knowledge as co-created then we embrace a more collaborative view of education. We can prepare students to become agents of their own learning (Leslie, 2015). This research aims to investigate one format of digital learning that can create for students an active and relational learning opportunity.

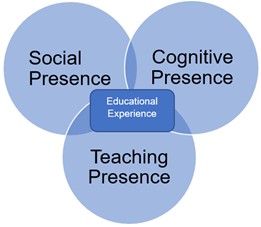

The COI model, shown in Figure 1, is comprised of three presences - teaching, social and cognitive. Each of these presences are “critical prerequisites” (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 2000, p. 87) and so are integral to the social construction of knowledge in online forums.

Figure 1

The Community of Inquiry Model

Note. (Garrison, Anderson, & Archer, 2000)

Dempsey and Zhang (2019) highlight the nature of the presences as a “three-factor higher order model” (p. 74) in which the presences are supported by 10 subfactors, or manifestations, of the presences. These factors are derived from an initial model developed by Arbaugh et al. (2008).

Table 1

Descriptions of Three Presences and Their Composite Elements

| Presence | Factor | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Design & organization |

|

|

|

| Facilitation |

|

|

|

| Direct instruction |

|

|

|

| Affective Expression |

|

|

|

| Open Communication |

|

|

|

| Group Cohesion |

|

|

|

| Triggering Event |

|

|

|

| Exploration |

|

|

|

| Integration |

|

|

|

| Resolution |

|

|

Note. (Based on Dempsey & Zhang, 2019)

The ‘inquiry’ within the COI model is ultimately derived from the learning objectives by the instructor, who poses a specific task to frame the inquiry. Table 1 shows that the inquiry is embedded in the teaching presence in the form of the ‘design’, underscoring the paramount importance of this presence. Teaching presence is also comprised of two other elements — facilitation, and direction. Students make significant contributions to teaching presence through their comments and questions which ‘facilitate’ the discussion. The instructor maintains the inquiry by providing continued ‘direction’ through responses to individual students. Both the original design and the facilitation of the discussion need to include metacognitive elements of how to engage with each other and the content (Garrison & Akyol, 2015) as much as what to engage about.

The contributions of teaching presence are moderated by social presence. To support the inquiry, the instructor and students must contribute to the social cohesion of the community. Table 1 shows that all participants must employ ‘affective expression’ and ‘group cohesion’ to ensure that those to whom they direct their comments feel valued and respected (Akyol & Garrison, 2008). ‘Open communication’ allows members to understand what others deem important.

Teaching presence moderated by social presence is the “cornerstone of the actualization of cognitive presence” (Garrison & Akyol, 2013, p. 64). Being present in the co-construction of knowledge involves first exposing your ‘self’ to the group through a triggering event, which is the response to the inquiry. This exposure needs acceptance through social presence in order to generate cognitive presence.

When each participant is socially present, they give each other permission to explore their ideas, and then to integrate those ideas as resolution to a question or to a transformative thought process. In order to support students to take on the challenge of their own learning, educators need to foster a sense of heutagogy, or self-determined learning (Kenyon & Hase, 2010), in their students. Combined with an openness to cwelelep, students will seek knowledge as part of their professional role, and then reflect on that learning, very much in the manner of Kolb’s (1984) experiential learning model.

The principal researcher has used discussion forums extensively over many years of teaching and has conducted previous research (Leslie, 2015) on discussion forums. Scenarios include a flipped classroom format where students engage with new content individually, then through discussion forums prior to coming together. In this mode, students are able to follow up face-to-face (F2F) with their peers.

Conversely, this study examines a distance modality in which a Master degree level course with an average enrolment of 20 students is conducted asynchronously following a semester-based schedule. Students have only one medium, discussion forums, through which to communicate with each other, highlighting the need to ensure that the use of this medium is understood by the students and the instructor.

This research will use the COI framework to examine the nature of the relationships and interactions between students within a series of course-based discussion forums. The focus was to examine the creation of cognitive dissonance as noted in the research question and its potential to increase cognitive presence, and to provide advice for educators who wish to provide a stronger learning environment for their students.

For this study, the authors analyzed the discussion forum activities of three cohorts of a Canadian Master degree-level course in Education. There was a total of 57 students, all of whom are Canadian, and most of whom are K-12 teachers, but with a small percentage of college level instructors or administrators. Most of the participants are located in several provinces across Canada, with several located in various countries including the United States, China, and the United Arab Emirates. One cohort was conducted in a summer semester, and the other two were conducted concurrently during the following winter session. All students agreed to allow their work to be included in the study, with eight agreeing to have their work quoted and to participate in interviews.

For clarity, Table 2 captures the nomenclature of the various elements. The discussion forum platform will be referred to as a discussion forum, whereas a discussion forum-based assignment will be referred to as a ‘forum assignment’. The initial response to the ‘Design’ question by any community member will be referred to as a ‘post’. The person who posts will be referred to as the ‘posting student’. Any responses will be referred to as ‘responses’, and those who respond to a post will be referred to as ‘respondents’.

The initial post of any participant is always coded as a ‘triggering event’. Responses are categorized as one of the nine remaining factors. The initial post plus any responses to that post by any member of the community will be referred to as a discussion.

Table 2

Nomenclature of Discussion Forum Elements and Interactions

| Element or Interaction | Term |

|---|---|

| Discussion forum platform | Discussion forum |

| Discussion forum-based assignment | Forum Assignment |

| Students or the instructor within a cohort | Community member |

| Initial post by any student as a triggering event | Post |

| Student who creates a post | Posting student |

| Response to a post | Response |

| Student who responds to a post | Respondent |

| Initial post plus all responses | Discussion |

The course syllabus includes five discrete, progressive, discussion forum-based assignments. Each forum assignment builds on the knowledge generated in the preceding forum. For example, the first forum asks for an annotated concept map of methods employed in the classroom to build community, while the second forum assignment asks for a discussion of the pedagogic approaches employed. Each forum is framed by an assessment rubric that details a word count of 500, and two due dates. The first due date is for each student’s initial post, and the second is for students’ responses to at least two other posts, and to all questions posed to their own post.

In an introductory module, students are provided online information and discussion about the COI model and the social construction of knowledge. Students are also provided with several journal articles, a link to a COI website (Athabasca University, n.d.) and an educational support blog post created by the author on how to improve the quality of their posts and responses. It should be noted here that while students had a general familiarity with discussion forums through the other courses within the Master degree program in which this course is placed, they had no knowledge of the COI model. This point will be discussed further in the findings.

Explicit reminders about metacognitive approaches to engaging in discussion forums are reinforced through repeated feedback, both collectively and individually in the forum assignments. For example, the instructor exhorts the students through individual feedback to ask their classmates questions and to respond to all questions posed to them. The instructor also models how to ask challenging questions that help students to expand on their initial posts in order to build capacity and inspire further responses.

This research investigates if these practices increase students’ acceptance and pursuit of cwelelep, thus creating the conditions for cognitive dissonance through the social construction of knowledge.

There are three data collection methods used across all three cohorts. The first involved an analysis of the content of the discussion forums using the COI measurement tool shown in Table 1. NVivo, qualitative data analysis software, was used to categorize all posts and responses across all of the initial and fourth of five forum assignments into instances of one of the 10 factors of presence, presented in Table 3. The initial forum assignments provide a baseline count of interactions. The fourth forum assignment provides a correlated count of the 10 factors after students have experienced the first three forum assignments. The fifth post is submitted at the end of the course along with the final assignment and so is not a fair indicator of the discussion forum interactions.

The second method was a structural analysis of the progression of interactions between students following timelines and the nature of the reciprocal interactions. From this analysis, clear patterns of interaction have emerged. The third method involves individual interviews with students who had successfully completed all components of the course and had received their grade for the course. In total, eight students agreed to the interviews with six completing the interviews with the principal author. The dispersal of students across time zones ruled out focus groups.

The principal author’s posts to the forum assignments were not included in order to avoid any skewing of results. The principal author was the sole rater reducing concerns of inter-rater reliability. The quantity of posts (over 900 in total) and the number of instances (slightly more than 2000) reduces concerns over subjectivity and bias on the part of the researcher.

Instances of presence are not defined by length or word count, although certain subfactors tend to have a generalizable length. For example, a response in the form of a single question or a short comment to a post codes under Teaching Presence as Facilitation, whereas a comment followed by a specific instruction, codes as Direct Instruction. Dempsey and Zhang (2019) comment that these two factors may need further study to help differentiate them.

Conversely, instances of cognitive presence can vary significantly in length. The triggering event post, required by the assignment to be approximately 500 words, is always categorized as a single instance of cognitive presence. Within the other factors that comprise cognitive presence, the distinction between instances of resolution is determined by whether they respond to more than one question. For example, expressions such as, “as for your second question”, or “on the other hand”, indicate separate instances, and possibly different factors, of cognitive presence.

Instances are also often categorized by paragraph. For example, three paragraphs of cognitive presence will code as three instances, whereas one long paragraph will code as one instance. In social presence, thanking someone codes as affective communication, whereas a lengthier ‘thank you’ that includes a statement of affirmation about the question codes as group cohesion. General, non-related comments code as open communication.

The results of the categorization are shown in Table 3.

Table 3

Categorization Count of the Ten Factors of Presence

| Forum Assignments in Order of Completion |

% of Total Instances | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st of 5 | 4th of 5 | % Change | 1st of 5 | 4th of 5 | |||||

| Total Posts | 453 | 460 | 2% | - | - | ||||

| Participants | 57 | 57 | - | - | - | ||||

| Average Responses / Student | 8 | 8 | 0% | - | - | ||||

| Design | 0 | 0 | 0% | 0% | 0% | ||||

| Direct Instruction | 32 | 7 | -78% | 4% | 1% | ||||

| Facilitation | 108 | 188 | 74% | 12% | 16% | ||||

| Total - Teaching Presence | 140 | 195 | 39% | 16% | 17% | ||||

| Affective Communication | 57 | 57 | 0% | 15% | 17% | ||||

| Group Cohesion | 132 | 213 | 61% | 15% | 18% | ||||

| Open Communication | 7 | 11 | 57% | 15% | 1% | ||||

| Total - Social Presence | 275 | 427 | 55% | 31% | 36% | ||||

| Triggering Event | 6% | 5% | - | - | - | ||||

| Exploration | 104 | 76 | -27% | 12% | 6% | ||||

| Integration | 170 | 161 | -5% | 19% | 14% | ||||

| Resolution | 139 | 261 | 88% | 16% | 22% | ||||

| Total - Cognitive Presence | 470 | 555 | 18% | 53% | 47% | ||||

| Total Instances of Presence | 885 | 1177 | 33% | - | - | ||||

| Average Instances of Presence per Post | 2 | 3 | - | - | - | ||||

The total count of posts and responses does not vary significantly between the first and fourth forum assignments. This is indicative of the forum assignment requirements which require from each student a triggering post, a minimum of two responses to peers, plus responses to all questions posed to them. This averaged to eight per person.

However, the total instances of presence increased by 33%. This indicates an increasing metacognitive understanding of the forum assignment parameters as students progressed through the course. It may also indicate an increasing pursuit of cwelelep and an appreciation of the consequences of their own actions in the forums as students accepted greater responsibility for their own learning.

The instances of design come exclusively from the instructor, and as noted were not recorded. Less frequently, but yet still significantly, students will offer direct instruction to each other. Generally, these communications are extrapolations from the triggering event. For example, one student suggested, “Check out this other blogger for great ideas … .” However, given the relatively short time frame for these courses, the students did not substantially diverge from the individual forum assignment directions. As the students became comfortable with the format, the instances of direct instruction declined by 78%.

Within a particular discussion, there are a number of response structures. For example, in response to a triggering event, a common response is to offer affective communication such as, “thanks for the informative post”. Such statements are often followed by a lengthier instance of group cohesion such as, “I love the idea of students listening to each other reading stories”, which in this example directly references the triggering event.

Next, the response may offer exploration as the respondent filters through elements of the triggering event such as, “I can imagine that in a rural environment it is difficult to plan around technology that is not reliable. In my classroom, I am lucky to be able to …”. This is often followed by integration such as, “you mention that your students have opportunities to …, which made me realize that I can greatly improve my project by …”. In turn, this statement might be followed by facilitation in the form of specific questions related to the initial content such as, “Currently, my project lacks certain reflective elements. Do you have any suggestions on how to improve these areas?” Almost always, facilitation is followed by affective communication, “thank you for sharing your thoughts”.

As students’ metacognitive understanding with the COI model increased, they became more at ease with each other, allowing an increase of 74% in facilitation in the fourth forum assignment, asking more questions, challenging ideas and pursuing cwelelep. An overall increase of 39% in teaching presence was supported by an increase of 55% in social presence.

There was an increase of 61% in group cohesion as the students learned to pose their questions in an appreciative manner. In extended exchanges, social presence often is minimized by omitting the greeting, but the group cohesion may be emphasized, “I agree, I would be nervous too”. This is often a precursor to a resolution which may start with, “Personally, I would …”. Open communication is less commonly seen and almost always in the context of the exchange. A common example is to restate the person’s comment, “for the most part your examples seem to be in support of … .” This type of clarification often leads directly to teaching presence such as a facilitating question, “So, do you …”.

Instances of cognitive presence overall only increased by 18%, however within that construct there was an increase of 88% in resolution. This may be a result of the increase in facilitation and group cohesion, which encouraged students to be more assertive in their responses. Interestingly, the instances of cognitive presence compared to all presences, declined between the two forums. The 27% decrease in exploration contributed to this decline as students focused on integration and resolution in the attempt to explain their thoughts.

In the fourth forum assignment, once a student posted a triggering event, they tended to put most of their further efforts into supporting or defending their work rather than further exploration. Once a response is received, commonly the posting student offers an integrating statement, “I agree that making more international connections could be beneficial … .” This is often a precursor to a resolution, “I have made genuine connections with fellow teachers and students using this group.”

The most notable structural element is the reciprocal action of responding to posts and other responses. One integral element of success is the timeliness of posts. While discussion forums are an asynchronous form of communication, the posts do need to be contained within the timeframe of the individual assignments. When students post outside of the set timeframe, there are generally few or no other students viewing that discussion forum to respond.

A related element refers to the temporal distance between responses. In instances where the temporal distance is minimal, there is often an extended exchange where more specific questions are pursued. The exchanges are also affected by factors such as participants’ timetables.

A third element relates to the response rate of individuals. Those who respond to more posts and responses tend to attract further comments from others. Other factors such as the quality and formatting of the post, and adherence to the word count also had significant impact on responses.

These elements and parameters speak to the notion of a narrative of learning (Leslie & Camargo-Borges, 2017) in which the community members must be cognizant of the medium through which they are communicating.

The individual interviews elicited the participants’ attitudes towards distance courses generally, their knowledge of the COI model, the efficacy of discussion forums as a tool for the creation of knowledge, how their perceptions of the discussion forum medium changed, and their level of comfort in challenging others. Themes that emerged included their interactions with the instructor both in the content of the forum assignments, and from the instructor’s varied efforts to encourage and instruct participation in the forums. Other themes concerned their interactions with the other students, their ability to adapt to the confines and processes of the medium, and in particular their response to the discussion forum as a source of credible, contextualized, and highly relevant new learning. For clarity, three themes were identified:

This instructor led by example, reading all posts and responses and offering demanding challenges. Such engagement provides a metacognitive direction in the formation of questions, thus expanding the nature of the teaching presence, and adding to the initial inquiry a wider range of contextualized questions and cognitive dissonance. For example, one participant, noted that in another program from which they ultimately withdrew, “there was no probing of ideas, there was no kind of formative learning”.

One student noted that the teaching presence offered in the course, “stimulated further conversation, asking questions and did not let it come to a finish line”, and that there was always, “an opportunity to push this one step further”. Another student noted that having the instructor say to her, “try to not just write, ‘great job’, but try to ask questions” was instrumental in her own development. She noted that, “I didn’t do that before, but I actually didn’t know that I should do that”.

Setting an example for asking demanding questions gives implicit permission to students to do the same. One student expressed gratitude that the instructor, “made a point of going in and stimulating further conversation and asking questions of the questions.” Another commented that when they noticed how the instructor asked challenging questions, “I realized you know, that people weren’t just doing that to be a jerk or anything. They were doing it to try and help me learn.”

As a result, there was an increased awareness of the potential of the discussions to provide new knowledge. One student noted that, “You really didn’t want to miss what he would say so you go through all the responses because he would be providing feedback.” Another noted that the instructor told them, “I can see if you were reading or not”, which demonstrated an individual level of attention to the discussions and community members. A third observed that, “In my first two courses, the instructors maybe weren’t as active, so I personally didn’t understand at that point how powerful the discussions were.”

The instructor’s support is critical to create conditions under which students can better interact with each other.

For all students, the ability to fit the course schedule into their general life and work schedules was paramount. One noted that, “the best thing was to be able to do my own thing at my own time.” Another noted that a face-to-face program, “would have meant up to an hour and a half traffic both ways and so losing those three hours twice a week was not beneficial”.

Students also noted that the asynchronous format provided ample time for reflection and further reading to confirm new learning or to examine instances of cognitive dissonance. One student mentioned, “I can go back and double check that I understand what the person is saying”, and added that, “I didn’t respond right away. So, I would read it first, step away and then come back.” Another student noted that, “I can edit my thoughts before actually posting.”

Additionally, the ability to take time to reflect was contrasted positively against synchronous, in-class discussions. One student noted that, “It's hard to get as many people's perspectives potentially in the same amount of time.” Another suggested that the discussion forums allowed for greater interaction and that, “I’ve learnt way more than I thought possible and I found it to be very interactive.” A third commented on her surprise at how much she could learn from interacting with other students since, “a lot of the learning that has happened has not come just from the course content or from the professor”.

One student appreciated the discussion forum as a modern-day classroom analogue with the added benefit that, “there is a sense of openness and you are not as guarded.” This student added that as the course progressed, she felt more comfortable with her classmates noting that, “You can ask them a challenging question and you will get a response that fosters that sort of learning experience.” In each of these comments, students demonstrate an increased willingness to embrace uncertainty and actively seek out cognitive dissonance, pushing themselves into a state of cwelelep.

The third theme explored participants’ familiarity with and understanding of the COI model during the course. None of the participants in the study had heard of the model until being introduced to it through the principal author’s instruction, shared readings, and personal blog postings about the model. However, as the course progressed all participants noted how their perceptions of the discussion forums as medium of interaction changed very positively.

For example, they noted that they were unaware of the power of the content within discussion forums. One student commented that,

“Oh, I gotta click on all these to make sure I’m reading them but then I started realizing why, it’s like it was okay this is actually really powerful. I had now realized the importance of it so I didn’t have to be dragged along anymore — I could see okay well this power for me to do this is real.”

As the course progressed, there was a clear development of metacognitive awareness of teaching presence from the students, with a concurrent increase in their comfort level of challenging their peers. One student noted that, “Now I am trying to not just ask a question that I want to know, but maybe ask a question that will benefit that person. It took me awhile to get to that point.” A different student commented, “How can I further their thinking – just to help them along just as an educator or a leader in education”. Notably, a third student commented,

“I think the big things that helped me was reading other people's, and trying to answer the questions that they had. So when I read someone else's, I actually connected and I had an answer for them. It made me feel very excited, because I was like, look, I'm helping this individual.”

Others noted that they increasingly focused on the nature of their contributions to teaching presence stating that,

“You know, if there's a lot to think about when you ask a question so I did find that a little more challenging. I went in trying to find the right way to ask a question every time, because [the instructor] had encouraged it but I didn't always find it easy.”

Some noted an even finer attention to the nature of their teaching presence, stating,

“And so, I started to realize that when I was asking questions and probing deeper into some of the content, I was not only asking questions about the content, but also linking that to experience. So, I think for me, just making that link, that connection between the theory, and the personal experiences — that was big for me.”

When asked about other thoughts on discussion forums, students provided a range of comments about the potential of connecting the learning content to the personal experience. For example, one student suggested that,

“When people write a discussion post that is directly related to their personal experience, I find that’s easier to talk about or challenge or explore further, because you already have a level of confidence with that knowledge.”

These comments show the potential of the discussion forums to provide an environment where students feel motivated to pursue uncertainty and experience dissonance. By connecting the content to their personal experiences, challenging others to do the same, and sharing these interpretations with their community, students generate place-based, relevant learning that challenges their own perceptions and biases towards new concepts.

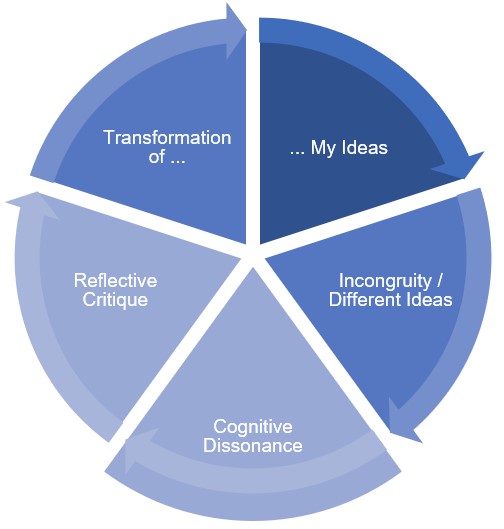

Figure 2 shows the COI model as a process through which the elements of the model create the conditions under which knowledge may be socially constructed.

Figure 2

Community of Inquiry as Process

Teaching presence must include the role of inspiring cwelelep — of putting ourselves in a state of uncertainty. If students are made explicitly aware that they have not only the ability, but the responsibility to direct the nature of the inquiry through their challenges and questions, they will accept that responsibility. This approach also allows for Etuaptmumk, as they learn to view the world through other viewpoints.

Not only do they need to challenge others, but they need to accept challenges from others. In this study, students began to knowingly and willingly push themselves into a state of uncertainty — a state of cwelelep. Although we learn through cognitive dissonance, we often instinctively try to push towards certainty rather than uncertainty in our work, especially when we will be graded on our performance.

Initially, students are often reticent to issue challenges. Hesitations come from their affective beliefs in their own ability, and from their desire to ‘be nice’. Explicit metacognitive instruction in the nature of teaching presence helps to alleviate these concerns.

Further explicit instruction in the nature of social presence then gives students permission to issue those challenges to their peers. Concurrently, as they receive challenges from their peers that have been mediated by affective communication strategies, they begin to feel confident in issuing their own challenges in a positive feedback loop. This feedback loop highlights the overlapping roles of teaching and social presence to inspire cognitive presence and the social construction of knowledge.

A critical element of the COI model is that the instructor is an active participant in the forums. The first theme, ‘level of support from the instructor’, highlighted the need for the active teaching and social presence of the instructor, offering up his or her own cognitive presence in the form of narratives of learning (Leslie & Camargo-Borges, 2017).

It is this “committed judging and caring action” (Kelchtermans, 2009) in the forums that helps create the conditions needed for learning. Once students realized in the first forum assignment that the instructor could see their activity, and was leaving new ideas in the form of constructive feedback throughout the forum, they started to read widely. This had the effect of exposing them to the ideas of their peers in their efforts to apply theory to practice, which Freire (1998) tells us is a requirement of learning. The cognitive dissonance that arose from the multiple perspectives encountered builds on the concept of circles of participation as described by Gergen (2009), and supports two-eyed seeing (Bartlett et al., 2012).

In contrast to a F2F format, the participants enjoyed the time afforded by the asynchronous format to reflect on their peers’ ideas before responding. Being an educator amongst other educators, they noted feeling daunted by the weight of their peers’ experience. By being able to share carefully considered responses, they were able to gain confidence in both the medium and their own work. A relational approach to understanding our experiences from different perspectives promotes deeper understandings of our own context (Newbury, 2020).

The third theme, ‘perceptions of the discussion forums’, highlights a positive change toward the discussion forum as a medium of study. The fact that the discussion forums are preserved for later reference enhanced students’ ability to learn from their peers. As was noted, in a ‘live’ in-class discussion, they might be dominated by other students. In the discussion forum, all students had equal opportunity to participate. A classroom atmosphere did exist and was supported by social presence. This resulted in a rewarding learning experience for all of the participants.

Notably, most students expressed some surprise that they found such inspiration and new learning in the discussion forums. There was a tension between the familiar in-person format and the unfamiliar experience of being at a distance and having to take greater responsibility for their own learning. Students embraced the First Nations principle that learning involves recognizing the consequences of their actions within the forums.

The purpose of discussion forums is to offer a medium where course content and assignments can be examined in relation to the students’ experiences and prior knowledge. It is in these forums that students, in a distance modality, have the best opportunity to create the conditions under which they can pursue and clarify their own uncertainties towards their studies.

This research presents key elements of the COI model that will enable the design of an engaging online educational space.

Student-centered learning approaches highlight the need for a confluence of course objectives and student goals. Instructors need to present well-designed forum assignments and questions that are explicitly related to larger assignments and the course objectives. This provides metacognitive direction through the design factor of teaching presence on how to effectively present their ideas — and this makes a place for the pursuit of cwelelep. A good assignment tells students that ‘here you will explore what you do not know’.

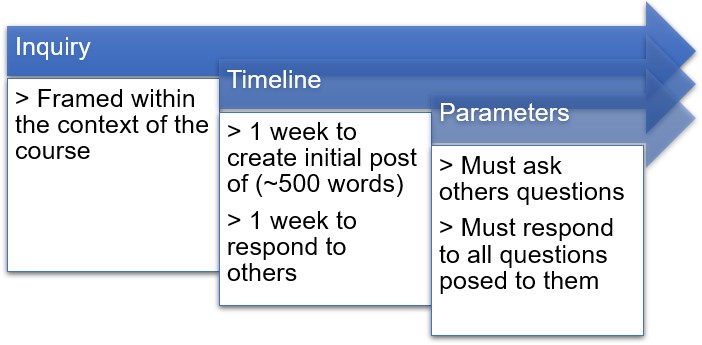

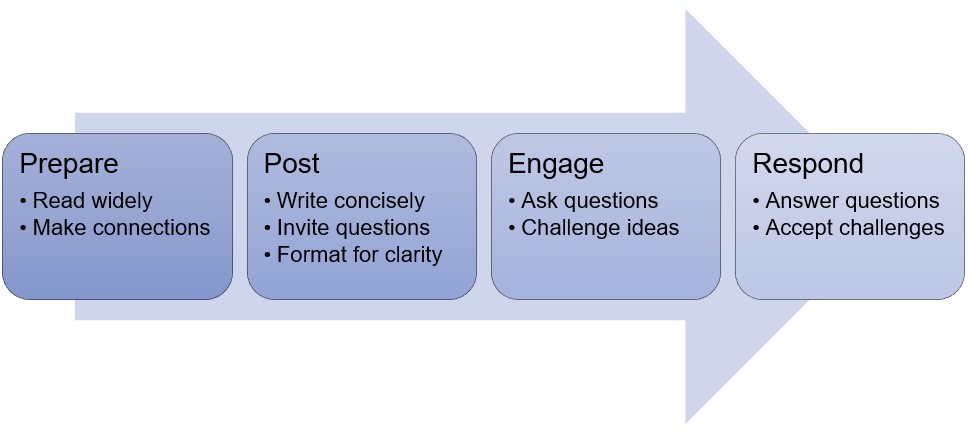

To strengthen metacognition around the learning process, instructors need to provide explicit instructions within assignments concerning student responses to the inquiry as shown in Figure 3. First, the forum assignment requires two deadlines. One is for the initial post. The second is to afford students time to reflect on the posts and share their responses.

Figure 3

Designing an Inquiry

Once the inquiry is ready, the assignment written, and the course started, the instructor must explicitly explain the conditions that have been created. This can be a relatively simple communication as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

How to Respond in a Discussion Forum

Prepare. Students must be encouraged to relate the content to their own experiences, and their community. Students tend to prefer certainty, and so need to be encouraged to instead look for uncertainty.

Post. Students need explicit metacognitive instruction on writing posts including how to share questions that remain in regard to the content. In order to facilitate the discussion, students must make their initial post within the assignment time span.

Students need to write concisely within the assigned word length, which at 500 words, is sufficient to allow all participants time to read several posts. The forum medium demands a ‘brisk’ writing style, using short paragraphs, bullet points, and other formatting features to allow respondents easy access to the ideas within.

Engage. Students need direction to ask challenging questions. This pushes them to carefully read their peers’ work in order to formulate good questions. In turn, this creates further facilitation and exploration, allowing alternate perspectives to emerge. It is at this point that students experience cognitive dissonance and the realization that they may be learning something. As one student noted, “I had now realized the importance of it so I didn’t have to be dragged along anymore — I could see okay well this power for me to do this is real.” It is here also that students will start to engage in two-eyed viewing.

Respond. As they are challenging their peers, their peers will be challenging them. In this phase, ideas are formulated, challenged, and reformulated. There is integration and resolution. The more challenges there are, and the more challenging the exchanges, the more responses there are thus leading to more challenges in a positive feedback loop, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5

Cognitive Dissonance as Feedback Loop

Once the assignment is set and started, the instructor then needs to demonstrate teaching presence in the discussion, facilitating the discussion through challenging questions. The instructor also needs to be socially present, encouraging the students with appreciative feedback. Finally, the instructor needs to share their own pursuit of cwelelep and cognitive presence through exploration, and integration. As this student noted, ““I think the big things that helped me was reading other people's, and trying to answer the questions that they had.”

A significant limitation in the study is that there is no follow up with individual students in subsequent cohorts. Further interviews with the participants would reveal other instructors’ familiarity with the COI model and their efforts to sustain this approach.

Similarly, a survey or interviews with other instructors would reveal the extent of familiarity with the COI model within the institution.

To support the social construction of knowledge through this model, there needs to be an institutional buy-in that provides support to instructors who are not familiar with the COI model, or who have not had success with the model.

Education has gone digital, affording great advances in opening distance education opportunities to people worldwide. UNESCO (UNESCOb, n.d.) provides an extensive array of digital platforms and technologies that support distance learning around the world. Recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has only served to push many more learners and institutions online. While it may be argued that real-time, face-to-face learning is preferable, for many millions of people distance education offers great hope for individual futures built on education and learning.

The context of this research is within a distance learning format. The student participants are themselves teachers or related professionals, and adult learners with full-time ‘day’ jobs, families, and other societal pressures, who have willingly enrolled in their program and so have accepted their responsibility as a student. In the face of such student aspirations for their own future, we argue that it is incumbent on educators to provoke engagement towards the construction of knowledge rather than focusing on the transmission of knowledge. Similarly, many K-12 curricula, within Canada and further abroad, have an increasing focus on skills development including metacognitive strategies that promote self-directed learning.

The findings of this research indicate that discussion forums are a medium with the potential to increase the quality of engagement between students by providing metacognitive direction and facilitation, thus provoking a focused cognitive dissonance. By offering challenges coached in appreciative language that encourages future forming responses, community members can create for themselves the conditions under which learning can occur.

Community members can use the discussion forum medium to help each other form coherent narratives of their educational journey and new learning. These narratives may be referred to as ‘bundles of knowledge’ (Ravensbergen, 2019) or ‘narratives of learning’ (Leslie & Camargo-Borges, 2017). These narratives may also include two-eyed seeing as a means of better understanding our world. McLuhan (1964) discusses media as a translator and notes that through modern technology we can “translate more and more of ourselves into other forms of expression that exceed ourselves” (p. 57). Thus, the type of media used, and how, becomes critical in shaping the message. Purposeful use of discussion forums can lead to a generative approach to learning whereby students are exposed to each other’s perspectives on any given question and challenged to make “innovative constructs” (Camargo-Borges, 2019).

One of the student participants captured a revelational moment in her metacognitive development, commenting that, “You ask them a challenging question and you get a response that fosters a learning experience”. All students reported having a moment when they realized they were actually learning something meaningful, beyond just the content, from the forums. At this point, the entire process of engagement crystallizes for them as they realize that their own individual stories will become part of a bigger story. They begin to engage in the forums with intention, and feel they are a part of a community of inquiry.

Arbaugh, J. B., Cleveland-Innes, M., Diaz, S. R., Garrison, D. R., Ice, P., Richardson, J.C., Swan, K.P. (2008). Developing a community of inquiry instrument: Testing a measure of the community of inquiry framework using a multi-institutional sample. The Internet and Higher Education, 11(3-4), 133-136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.06.003

Akyol, Z., & Garrison, D. R. (2008). The development of a community of inquiry over time in an online course: Understanding the progression and integration of social, cognitive and teaching presence. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 12(3-4), 3-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.24059/olj.v12i3-4.1680

Athabasca University. (n.d.). The community of inquiry. https://coi.athabascau.ca/

Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., Marshall, A. (2012). Two-eyed seeing and other lessons learned within a co-learning journey of bringing together Indigenous and mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 2(4), 331-340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8

Camargo-Borges, C. (2019). A-ppreciating: how to discover the generative core. In D. Nijs (Ed), Advanced Imagineering (pp. 90-104). Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

Camargo-Borges, C. (2015). Designing for learning: Rethinking education as applied in the Master in Imagineering. World Futures. The Journal of New Paradigm Research. Special Issue: On Imagineering as Designing for Emergence and Some Implications for Education and Research, 71(1-2), 26-39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2015.1087238

Camargo-Borges, C. & Moschetta, M. (2014). Health 2.0: Relational resources for the development of quality in healthcare. Health Care Analysis, 24(4), 338-348. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-014-0279-2

Dempsey, P. R. & Zhang, J. (2019). Re-examining the construct validity and causal relationships of teaching, cognitive and social presence in community of inquiry framework. Online learning, 23(1), 62-79. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v23i1.1419

First Nations Education Steering Committee. (n.d.). First Peoples principles of learning. http://www.fnesc.ca/first-peoples-principles-of-learning/

Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom: ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Garrison, D. R. & Akyol, Z. (2013, April). Toward the development of a metacognition construct for communities of inquiry. The Internet and Higher Education, 17(1), 84-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2012.11.005

Garrison, D. R. & Akyol, Z. (2015, January). Toward the development of a metacognition construct for communities of inquiry. The Internet and Higher Education, 24(1), 66-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2014.10.001

Gergen, K. J. (2009). Relational being: Beyond self and community. Oxford University Press.

Gergen, K. J. (2015). An invitation to social construction. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Hammack, P. L. (2018). Social psychology and social justice: Critical principles and perspectives for the twenty-first century. In P. L. Hammack (Ed), The Oxford Handbook of Social Psychology and Social Justice (pp. 1-67). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199938735.001.0001

Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Who I am in how I teach is the message: Self-understanding, vulnerability and reflection. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(2), 257-272. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600902875332

Kenyon, C., & Hase, S. (2010). Andragogy and heutagogy in postgraduate work. In T. Kerry (Ed), Meeting the challenges of change in postgraduate education. Continuum International.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning. Prentice-Hall.

Leslie, P. (2015). Narratives of learning: The portfolio approach. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

Leslie, P., & Camargo-Borges, C. (2017). Narratives of learning: The personal portfolio in the portfolio approach to teaching and learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(6). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i6.2827

McLuhan, M. (1964). Understanding media. MIT Press.

Newbury, J. (2020). Inclusion and community building: Profoundly particular. In S. McNamee, M. Gergen, C. Camargo-Borges and E. F. Rasera (Eds), The Sage Handbook of Social Constructionist Practice. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Ravensbergen, L. (2019) Defiance, reclamation, and a call to Mino Bimaadiziwin/ The good life through ceremonial performance praxis. (Unpublished Master dissertation). Queens University.

Roher, S. I. G., Yu, Z., Martin, D. H., & Benoit, A. C. (2021). How is Etuaptmumk/Two-eyed seeing characterized in Indigenous health research? A scoping review. PLoS One, 16(7), e0254612. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254612

Sanford, K., Williams, L., Hopper, T., & McGregor, C. (2012). Indigenous principles decolonizing teacher education: What we have learned. In Education, 18(2), 18-34. https://doi.org/10.37119/ojs2012.v18i2.61

Statistics Canada. (2020, November 25). International students accounted for all of the growth in postsecondary enrolments in 2018/2019. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/201125/dq201125e-eng.htm

UNESCO a. (n.d.). Mobile Learning.https://en.unesco.org/themes/ict-education/mobile-learning

UNESCO b. (n.d.). Distance learning solutions. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/solutions

UNESCO. (2020, June 22). Education in a post-COVID world: Nine ideas for public action. https://en.unesco.org/news/education-post-covid-world-nine-ideas-public-action

Dr. Paul Leslie, Queens University, Canada

Paul Leslie, Ph.D. is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Queen’s University, Canada. He brings a global perspective to his teaching from his experiences teaching and learning in such places as Korea, Brunei, the UAE, Australia, The USA, Barbados and Canada. He has taught in K-12, undergraduate, and Master’s programs. Email: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9465-2955

Dr. Celiane Camargo-Borges, Breda University of Applied Sciences, Netherlands

Celiane Camargo-Borges, Ph.D. is Lecturer and Researcher at Breda University of Applied Sciences, The Netherlands, and a member of the Executive Board of the Taos Institute. Working with constructionist theory, she is also the founder of Designing Conversations (designingconversations.us) where she consults in dialogical processes and designing research. She is a co-editor of The Sage Handbook of Social Constructionist Practice. Email: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8451-0056

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.