Vol. 37, No. 2, 2022

https://doi.org/10.55667/ijede.2022.v37.i2.1270

Abstract: This article explores the importance of providing Open Distance Learning (ODL) students with support that is more personalized. With this type of support, students sense that they have been treated with human kindness. Also, the individuals offering support focus primarily on relationship building, and fostering a sense of community and care amongst online students. Literature reveals the importance of online student support that addresses affective, cognitive, and systemic needs. However, enough is not known about the value of having a role whose sole focus is personalized affective support in an online learning environment. Within a qualitative approach, the study used 12 semi-structured interviews and five focus groups with 34 participants to explore the value ODL students place on non-academic support. The findings revealed that participants knew who their Programme Success Tutor (PST) was. However, for various reasons, there was not a shared or common understanding of the role of a PST as one that is intentionally affective in nature. Based on the findings, the study suggests that a PST or a similar role at an ODL institution should be closely aligned with the needs and expectations of the students. This is the vision for which the PST role was created. We further recommend using Karp’s four non-academic support mechanisms as a framework when establishing or revising such a support role.

Keywords: open distance learning, student support, programme success tutors, personalized support, humanized support

Résumé: Cet article explore l'importance de fournir aux étudiants en formation ouverte à distance (FOAD) un soutien plus personnalisé permettant aux étudiants de se sentir traités avec humanité. Les personnes qui offrent ce soutien se concentrent principalement sur l'établissement de relations et sur la création d'un sentiment de communauté et d'attention parmi les étudiants en ligne. La littérature révèle l'importance du soutien aux étudiants en ligne qui répond aux besoins affectifs, cognitifs et systémiques. Cependant, on ne connaît pas suffisamment la valeur d'un rôle dont le seul objectif est le soutien affectif personnalisé dans un environnement d'apprentissage en ligne. Dans le cadre d'une approche qualitative, 12 entretiens semi-directifs et cinq groupes de discussion avec 34 participants ont été réalisés pour explorer la valeur que les étudiants en FOAD accordent au soutien non académique. Les résultats ont révélé que les participants savaient qui était leur tuteur de réussite de programme. Cependant, pour diverses raisons, il ne semblait pas exister de compréhension partagée ou commune du rôle d'un tuteur de réussite de programme et de la nature intentionnellement affective de celui-ci. Sur la base des résultats, l'étude suggère que le rôle de tuteur de réussite de programme ou un rôle similaire dans un établissement d'enseignement ouvert et à distance devrait être étroitement aligné avec les besoins et les attentes des étudiants. C'est la raison pour laquelle le rôle de tuteur de réussite de programme a été créé. Nous recommandons en outre d'utiliser les quatre mécanismes de soutien non académique de Karp comme cadre lors de la création ou de la révision d'un tel rôle de soutien.

Mots-clés: formation ouverte à distance, soutien aux étudiants, tuteurs de réussite de programme, soutien personnalisé, soutien humanisé

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

“No man is an island” is a turn of phrase taken from a sermon delivered by the English poet, John Donne in 1642. In this sermon, Donne was speaking to the notion that all human beings are connected and the belief that feeling part of something bigger than ourselves is intrinsic to an individual’s sense of emotional well-being (Carey, 2011).

Research suggests that this need for community and connection also translates into the Open Distance Learning (ODL) environment (Makhanya et al., 2013). As Kahu et al. (2013) propose, making connections with peers in the online learning environment can minimize feelings of isolation. Park et al. (2011) add to the discussion by suggesting that without a sense of connection to others, the risk of students withdrawing from online engagement remains high. Within an ODL context, several factors are said to contribute towards student attrition. A factor that contributes to student attrition is the sense of physical and academic isolation ODL students report experiencing (Angelino et al., 2009; Kahu et al., 2013, Park et al., 2011). These findings echo the work of Barrett and Lally, 2000; Rovai et al., 2007; and Visser and Law-van Wyk, 2021, who found that the isolation experienced by students had a direct impact on student satisfaction and attrition rates among those engaged in post-secondary studies.

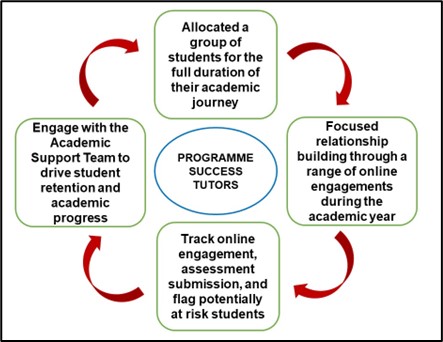

In 2016, a South African private higher-education institution (PHEI) launched its ODL model. The role of the Programme Success Tutor (PST) was central to their development of this model. The primary focus of individuals in the PST role is to build relationships and foster a sense of community and care, specifically amongst online students. Although the PST is part of the institution’s academic team, their role is not to provide subject matter expertise, but rather to ensure students understand there is a real human presence in what may feel like a lonely environment (Kaufmann & Vallade, 2020). Within this ODL structure, each PST is allocated a group of students with whom they engage, starting when the student registers and continuing until the student graduates. Engagements between the PST and student take place online, or over the telephone, at regular intervals during each semester. The primary aim of the engagement sessions is to ensure students remain aware of this affective support mechanism available to them via the PST role. Figure 1 below provides a visual summary of the PST role and responsibilities.

Figure 1

A Summary of the Programme Success Tutor Role

Note.Adapted from Exploring Connections in the Online Learning Environment: Student Perceptions of Rapport, Climate, and Loneliness, (https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1749670). Long description of Figure 1. A Summary of the Programme Success Tutor Role

A review of the literature reveals the importance of online student support and highlights the significance of student emotional well-being in an ODL context, including the need for affective, as well as cognitive and systemic support (Netanda et al., 2019; Shikulo & Lekhetho, 2020; Tait, 2000, 2014). However, the literature neglects to explore the value in having a role whose sole focus is personalized affective support in an online learning environment. This study aims to address this apparent gap by interrogating the need to provide ODL students with support that is more personalized in nature; in other words, support that gives students the sense of being treated with human kindness. The research question at the centre of this study is:

What value do ODL students place on having a dedicated support mechanism focused on ensuring their emotional well-being?

We will now address the conceptual framework at the centre of this study and the focus provided by a review of the literature. After explaining the methodology, we will discuss the main findings, and offer our conclusions and recommendations. In closing, we will acknowledge the limitation of this explorative study.

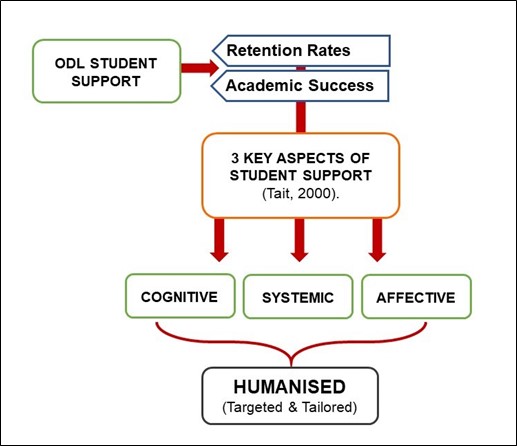

The provision and nature of student support for ODL students is central to the conceptual framework of this study. The work of Tait (2000, 2004, 2014) has been selected to provide the foundation for this framework, as shown in Figure 2 below and later discussed.

Figure 2

Targeted and Tailored Student Support

Note.Adapted from Planning Student Support for Open and Distance Learning (https://doi.org/10.1080/713688410) by A. Tait (2000); On Institutional Models and Concepts of Student Support Services: The Case of the Open University UK (http://www.c3l.uni-oldenburg.de/cde/support/fa04/Vol. 9 chapters/KeynoteTait.pdf) by A. Tait (2004); and From Place to Virtual Space: Reconfiguring Student Support for Distance and E-Learning in the Digital Age (https://doi.org/ 10.5944/openpraxis.6.1.102) by A. Tait (2014).Long description of Figure 2. Targeted and Tailored Student Support

According to Rotar (2022), citing LaPadula (2003), Ryan (2004), and Tait (2014), it is widely recognized that providing support for online students is essential. Rumble (2000) concurs, suggesting student support is closely linked to both retention rates and academic success. However, rather than mechanistic support, such as is available via “advanced technological and pedagogical tools,” Rotar (2022, p. 3) suggests the need for a more humanistic approach. Citing Thorpe (2002), Rotar defines this humanistic support as being more personalized, and more targeted and tailored to the specific needs of the student. Tait (2014) agrees and posits that although course content and learning resources are standardized and uniform for all students, student support has to be tailored for individuals and students in groups. The need for a humanistic approach to student support has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic because it enables students with specific challenges to persist and continue with their studies in difficult times (Burns et al., 2020; Matizirofa et al., 2021).

Tait (2000, p. 2) breaks down student support into three key aspects, each of which is “truly interrelated and interdependent:” cognitive, systemic, and affective. Cognitive support is associated with the “course material and formal learning support resources.” Systemic support relates to “effective administration and information management services that are transparent and student-friendly”. Affective support refers to the learning environment and its impact on student “commitment and self-esteem,” as well as the student’s “emotional or social environment.” Affective support is also referred to by other sources as non-academic support (Karp, 2011; Fynn & Janse van Vuuren, 2017; Waight & Giordano, 2018). This is the aspect of support that most closely aligns with the intention of nurturing a student’s sense of belonging and well-being in an online learning environment. The notion of affective support was used to inform the development of the PST role and is also the focus of this study.

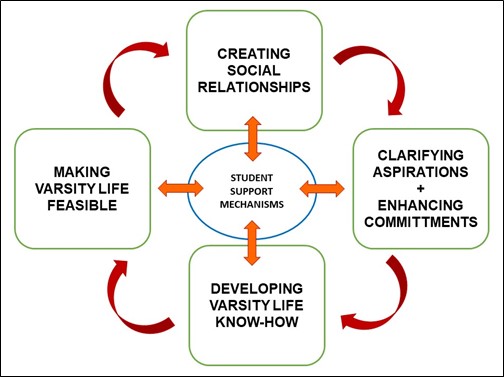

According to Karp (2011), a sense of belonging, or having the confidence to share who you are with your online peers, does not simply manifest the moment a student enrols in an online program of study. There has to be a deliberate and focused effort on establishing and sustaining an emotionally supportive environment. Karp (2011, p. 5) suggests four mechanisms for doing this, and defines mechanisms as the “things that happen” within programs or activities to support students and help them succeed in their post-secondary education and graduate.” The four mechanisms Karp proposes are: creating social relationships; clarifying aspirations and enhancing commitment; developing varsity life know-how; and making varsity life feasible. Figure 3 below illustrates these mechanisms.

Figure 3

Karp’s Student Support Mechanisms

Note. Adapted from Towards a New Understanding of Non-Academic Student Support: Four Mechanisms Encouraging Positive Student Outcomes in the Community College (http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/178542) by M. M. Karp (2011).Long description of Figure 3. Karp’s Student Support Mechanisms

Creating social relationships is linked to the assertion that social relationships can play an important role in promoting persistence. When students feel comfortable and safe, they are more likely to ask for assistance or request access to information, both of which can facilitate their path to academic success (Karp, 2011). Bensimon (2007, p. 443) concurs and refers to ways in which institutional agents can be called upon to facilitate these connections and build interpersonal relationships.

Grubb (2006, p. 197) suggests that students who do not have clear goals or a genuine understanding of the importance of post-secondary education are more likely to be “derailed by relatively minor challenges and setbacks.” Non-academic support that can assist students in clarifying their goals and aspirations enhances commitment and leads to students who are more likely to persist because they have a better understanding of what they are doing and why (Karp, 2011). Chase (2010) and Davidson and Wilson (2013) add to this assertion by suggesting that the more students relate positively to their learning environment and the institution with which they are registered, the more likely they are to view their academic pursuits as important and worthwhile.

Karp (2011) posits that managing student expectations is key to encouraging positive outcomes. Students who have a sense of “varsity life know-how” have an improved chance of settling down faster and progressing sooner. Davidson and Wilson (2013) agree, arguing that students need to understand the institutional rules of engagement. Karp (2011, p. 14) posits that, “failure to persist is more often a function of poor understanding and internalisation” of the organizational ethos than it is of “poor academic performance.”

According to Karp (2011, p. 19), day-to-day life can sometimes interfere with a student’s focus and ability to stay on track with their academic commitments. She suggests that having a mechanism in place that can occasionally provide students “with a little nudge” will go a long way in helping them overcome “small obstacles which, if left unaddressed, might become large enough to stymie their progress.” This is supported by the work of Lee et al. (2013) and Robertson (2020), who suggest external factors, such as the demands of work, family responsibility, and other conflicting commitments, can have a direct and significant impact on student retention and academic success.

In the conclusion of this paper, we address how the PST role, or similar roles, can fulfil the expectations of the four mechanisms proposed by Karp (2011).

A perusal of the literature reveals the themes that dominate the discourse on emotion within an educational environment. Conventional Western thinking would have one believe emotion is diametrically opposed to reason (O’Regan, 2003; Zembylas, 2008). This type of thinking would also have one believe feelings are inferior to thinking and should not be trusted (Damasio, 1999). O'Regan (2003, p. 78) adds that there has been “a consistent and entrenched belief that emotions are erratic and untrustworthy, and that for sanity and civility to prevail, rationality and intellect must function unfettered by the vagaries of emotion.” Such traditional views even go so far as to suggest, “the truth [can] only be reached when humans [are] completely devoid of subjectivity and emotions” (Zembylas, 2008, p. 4), and emotions stand as “obstacles to reason and the development of knowledge” (Dirkx, 2008, p. 11). According to Mortiboys (2012, p. 7), this type of thinking has become entrenched in the culture of higher-education institutions, where universities are viewed as “emotion-free zones,” along with a “tendency to downplay the affective domains of learning as emotions are considered private and should be controlled.”

The suggested disconnect between emotions and reason, and the ongoing need to separate thinking from feeling, may stem in part from the complexity of providing a clear definition of what constitutes emotion. As LeDoux (1999, p. 14) explains, “everyone knows what [emotion] is until they are asked to define it.” There are those, however, who strongly support the idea that emotions are inherent to the human condition, and to ignore emotion in the human response is to ignore a central element of the human experience (Cleveland-Innes & Campbell, 2012; LeDoux, 1999; Plutchik, 2003; Stets & Turner, 2006; Wosnitza & Volet, 2005). Solomon (2008), cited in Bharuthram (2018, p. 28) succinctly captures the importance of emotions when he states that, “we live our lives through emotions, and it is emotions that give our lives meaning.” However, the way in which emotion is perceived and regulated, is shaped by the socio-cultural contexts in which it exists. As an example, Kim and Sasaki (2012) argue that East Asians are less likely than European Americans to disclose distress, and seek or acknowledge emotional support. Language, values, socio-economic status, and health are more examples of socio-cultural differences that can influence how individuals view emotion (Akhter & Sumi, 2014).

Turning specifically to the ODL context, Pekrun and Stephens (2010) note the number of studies addressing students’ emotions has begun to increase over the last decade. However, the majority of these studies seem to focus on either the types of emotions experienced by online students, or the linkage between emotion and establishing social presence in the online environment. Christie et al. (2008, p. 570) note that becoming a university student is an “intrinsically emotional process.” The authors refer to the “culture shock” students experience when confronted with unfamiliar rules of engagement and the resulting “anxiety [of] not knowing what is expected.” Others in the field highlight the uncertainty and associated fear students experience when faced with the online environment. Students may find in the online environment the materials and assessments are presented in new and unusual ways, and the processes they are expected to follow may seem unclear or inadequately explained (O’Regan, 2003; Pekrun & Stephens, 2010; Weiss, 2000; Williams, 2017). These negative emotions may be further compounded into anger, or even shame, if students receive less than favourable feedback on the work they submit or they fail assessments (Pekrun & Stephens, 2010; You & Kang, 2014). However, these negative emotions may be tempered once students grow more accustomed to the requirements of online engagement and are able to experience a sense of success. Pekrun and Stephens refer to this sense of success as “achievement emotions.” The positive emotions students report once they feel more settled range from experiencing a “sense of stability” (Williams, 2017) to feeling motivated (Pekrun & Stephens) and even joyful (Zembylas, 2008).

One could argue that emotion cannot and should not be considered separate from the teaching and learning environment (Brookfield, 2006; Lehman, & Conceição, 2010; Lipman, 2003). Further, the impact of emotion on the student experience, and how this can be supported by a role such as the PST, warrants further investigation.

For the purpose of this study, a qualitative approach was adopted. This approach was selected because it is best suited to explore real-world subjects in which feelings and emotions play a pivotal role (Arghode, 2012). This qualitative study was prompted by an interest in the value students place on a non-academic support mechanism whose sole function is to provide affective support. As noted previously, the PST role has been strategically included in the ODL model of a South African PHEI. By engaging with students enrolled in this particular ODL model, we were able to gain insights into the perceived value students place on having access to this type of affective support during their academic journey.

Given that the PST role and the model within which it exists are an “individual representative of a group” that is bounded by space, time, and a specific context (Hancock & Algozzine, 2017, p. 15), the most suitable strategy was to do a case study. Because we were interested in the process, meaning, and understanding gained by engaging with distance students to whom a PST had been allocated, we adopted an approach that is socially constructed and descriptive (Creswell, 2021).

ODL students, who were enrolled in the PHEI and had been allocated a PST for the duration of their studies, provided the population for this study. Students enrolled with the PHEI resided in various locations across South Africa and were mainly based in urban and semi-urban areas. To ensure purposive sampling, an invitation to participate in this study was only sent to ODL students enrolled with the PHEI during the 2019 to 2021 academic year. The first 34 participants to respond who met the criteria were included and given the choice to either participate in the semi-structured interviews (SSI) or focus-group sessions. Six of the 34 participants had met the qualifications of their program and were ready to graduate just prior to this study being conducted. The remaining 28 participants were between their first and fourth year of study. Participants were not specifically included or excluded based on age, ethnicity, or where they resided, but rather on their ability to share their experiences of the PST role as students studying in a distance mode through the institution in question.

The decision was made to conduct all engagements fully online using the Microsoft Teams platform. This was done in order to accommodate the fact that participants did not reside in one centralized area, and two participants were based outside of the country. Sessions took the form of both SSI and focus-group interviews. This dual approach was adopted to allow for triangulation of the data by reflecting the individual experiences of certain participants, while also recognizing the collective or shared experiences of others within a group setting (Gill et al., 2008).

For this study, 12 SSI were conducted, and five focus groups were held, each with a minimum of four participants (for the “Interview Guide,” see Appendix A). Sessions were recorded with the consent of the participants and manual transcripts were made of each session. The reason for adopting a manual transcription process was to allow for a fuller emersion and the deeper understanding of the data that comes from hearing the students speak. The six-phase thematic analysis of Braun and Clarke (2006) was used to analyze the data. These authors define thematic analysis as a flexible method for the systematic identification and organization of data into patterns of meaning (Braun & Clarke, 2012). The six phases we followed were: 1) familiarizing ourselves with the data, 2) generating initial codes, 3) searching for themes, 4) reviewing the themes, 5) defining and naming the themes, and 6) writing the report. For the purpose of this study, we worked inductively, which means that the codes and themes were derived from the content of the data. However, as Braun and Clarke (2012) caution, it is impossible to be purely inductive, because we all bring preconceptions to the process of looking for codes and themes. This helped us determine if themes were relevant and worth coding. We coded individually and then coded together to ensure the consistency of the coded data. We used colour-coding to annotate the data, and then created categories and themes. In addition, we allowed for open coding to capture any data that represented new themes.

The overarching purpose of this study was to establish the value students place on having access to a role that is “targeted and tailored” (Tait, 2014) to providing affective student support. Participants were encouraged to share their understanding of the PST role as they had experienced it and were asked what importance they place on feeling emotionally supported during their studies. Participants were also asked for examples of the types of engagements they had with their PSTs and how having access to a PST for the duration of their studies impacted their academic journey.

Central to the concept of ethical research is the notion of informed consent (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). In order to meet this requirement, the purpose, focus, and nature of this study was shared with participants well in advance, as were the questions that guided the SSI and focus-group sessions. Members of the PHEI academic team conducted the SSI and focus-group sessions. Open engagement was encouraged, and every effort was made to establish an environment of trust during these online engagement sessions. It was explained to participants that the purpose of the study was to improve the student experience, and all feedback provided would be dealt with anonymously and with complete confidentiality. Participants were also assured that they were able to withdraw from the study at any point without reprisal. Ethical clearance to conduct the study was obtained from the PHEI, and further guided by the three fundamental principles of beneficence, respect for persons, and justice.

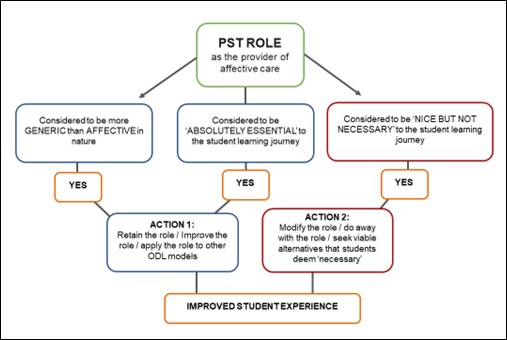

When conducting qualitative research, the most common criteria used to evaluate the trustworthiness of the study were credibility (truth), transferability (applicability), dependability (consistency), and confirmability (neutrality) (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Peer debriefing, triangulation, and member checking were used to establish credibility. According to Bitsch (2005, p. 85), transferability is established when the results of the research conducted can be applied to other contexts or settings through the “thick description and purposeful sampling” facilitated by the researcher. This study aimed to gain insights into the value of providing ODL students with a dedicated affective support mechanism. In doing that, we sought insight into whether providing dedicated affective support could potentially improve the learning journey of students enrolled in organizations outside of this study. Polit and Beck (2012) explain dependability as data that can be considered consistent across a range of similar settings or conditions. To ensure the dependability of this study, all processes were carefully recorded and reported in detail. Finally, confirmability is established when it is clear that the findings are not based on “figments of the [researcher’s] imagination but are clearly derived from the data” (Tobin & Begley, 2004, p. 392). As illustrated in Figure 4 below, there was no preferred outcome guiding this study. Any result would potentially lead to the same outcome—an improved student experience in an ODL context. Instead of allowing any personal biases to guide the findings, we relied on the rich quotes from the participants to lead the way.

Figure 4

Establishing Confirmability

Long description of Figure 4. Establishing Confirmability

The ODL model, which serves as a case study for this paper, was launched in 2016 by a South African based PHEI. Student numbers had reached approximately 20,500 at the time of this study, with at least 2,000 of those being distance students. The PST role was a central component of the student support mechanisms offered to the institution’s ODL students. The primary focus of the individuals in this role was to provide affective support and facilitate student emotional well-being. Each PST was allocated a group of students with whom they engaged for the full duration of the students’ academic journey.

As explained, 34 participants were included in this study, each of whom was enrolled with the institution for a qualification offered in the distance mode. Table 1 below provides a brief overview of the participants including their identifying pseudonyms and student status at the time of the study, and whether they participated in an SSI or focus-group session. As established, participants were not included or excluded based on age, ethnicity, geographical location, or other socio-cultural factors, but rather on the ability to share their personal experiences of the PST role in their capacity as distance students enrolled with the PHEI. All engagement took place online and sessions were recorded with the consent of the participants.

Table 1

General Participant Information

| Pseudonym | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ST01 | ||||

| DP02 | ||||

| AG03 | ||||

| MS04 | ||||

| AC05 | ||||

| SST06 | ||||

| BK07 | ||||

| EM08 | ||||

| EP09 | ||||

| MT10 | ||||

| AR11 | ||||

| TC12 | ||||

| NG13 | ||||

| CK14 | ||||

| GA15 | ||||

| SG16 | ||||

| QT17 | ||||

| BZ18 | ||||

| AA19 | ||||

| MVV20 | ||||

| DB21 | ||||

| AN22 | ||||

| AA23 | ||||

| SVR24 | ||||

| SL25 | ||||

| JCC26 | ||||

| TS27 | ||||

| TD28 | ||||

| JC29 | ||||

| JR30 | ||||

| MH31 | ||||

| RF32 | ||||

| MD33 | ||||

| TN34 |

During collection and analysis of the data set, the following three themes emerged. Each theme contributed to determining the value ODL students place on a support mechanism, such as the PST, that is focused on ensuring the students’ emotional well-being:

At the beginning of both the SSI and focus-group sessions, we began by providing the participants with background information about the PST role and its intended purpose as a provider of non-academic or affective support for students. It was evident from the responses we received there was very little common understanding of the PST role as having been specifically created to address the emotional well-being of students. When referring to the intended nature of PST support, participant AR11 indicated that he did not understand the role as being emotionally supportive, but rather as administrative or support of a more general nature. This gave rise to our first theme.

Although students were very familiar with who their PST was and could each recount having been engaged with their PST, they did not necessarily view the PST presence as being intentionally affective in nature. As two participants, AA19 and SVR24, shared:

AA19: Now that you explain it like that, I guess I can see the link, but I have to be honest, it’s not what I thought [redacted] was there for. I mean she does all of that, and I guess I would say that she is very involved and is happy to do whatever for all of us students and that’s great, but I didn’t really put that together with emotions, if you know what I mean?

SVR24: My PST is just like my go-to person, you know. So anything I need, and I am not sure of, I can just reach out and she is so quick to just put me straight… She is great.

Nine of the participants said their PST was “very involved,” and their PST “cared about” or “worried about” them. However, at least 20 participants referred instead to their PST in more general terms that did not directly imply affective support. For example, the participants said their PST was “great,” “helpful,” or “always available” to assist. Participants readily shared examples of their PST assisting them with academic counselling or administrative support. They said their PST discussed module choices, the registration process, and financial queries they may have had at the beginning of each semester. They also said their PST offered other support related to the institution’s systems and its learning management system (LMS), such as providing guidance on password access, platform navigation, and digital student cards (AR11; BZ18).

Although a lot of the anecdotal evidence shared by the participants was about generic support rather than affective support, it was nevertheless clear that certain students placed far more value in the support they received from their PST than other students did. This gave rise to themes two and three.

Sixteen participants indicated that the very reason they had enrolled for distance studies was because they preferred to work independently and at their own pace. As AN22 explained:

AN22: I am a self-starter; I like to work on my own and to just put my head down and do what needs to be done. I will say it was nice to hear from [redacted] and [the organization], you know, to get updates and maybe the odd reminder, but none of it was really information I could not have found out on my own if I needed to. So, for me specifically, I would say the support was a nice-to-have, but I wouldn’t say it was necessary.

Students who are willing to self-manage their learning, or intentionally elect to work in relatively unsupported isolation, seem to contradict the ideas of Shea (2006) and Cobb (2009) who suggest what distance students really want is to be part of an integrated community, and to experience a sense of cohesion and belonging. The urge for independence experienced by some students may be linked to their age. Eight of the more mature participants expressed an appreciation for PST support, but qualified this by also emphasising their sense of personal agency:

DP02: Having said that, I am also a mature student, so I’m very used to just getting on with things and getting things done on my own, you know. Just getting going, getting on without a dependency on other support, if I can say that. But it has been a bonus for me to have access to a PST. So, great to have, but for me personally, perhaps not totally essential.

From the above, it would seem participants who were slightly older, or perhaps more independent, preferred to manage their own learning and were less likely to seek assistance from their PST (AN22, DPO2, AR11, and RF32). Although age could be the main reason for a student’s independence and self-directedness, other socio-cultural factors, such as language, socio-economic status, and health, could also have contributed. Such socio-cultural factors fell outside the scope of this study. Follow-up research is needed to determine how these factors influence student’s dependence on a PST or a similar role. Two of the younger participants (SVR24 and BZ18) shared that they felt PST support was necessary throughout the year, and this led us to our third theme.

When asked to comment on why they placed so much importance on the support they received from their PST, participant SVR24 expressed the following:

SVR24: Oh, I place a very high importance on it—like, I need it. I’m young and my parents have always been there to take care of stuff, so I needed that person like [redacted]. I can’t sit and feel like I have no help, no one to just WhatsApp like [redacted]. I need that, so I would say it is absolutely essential throughout the year.

Participant BZ18 also had this to share:

BZ18: I would say the support is really necessary all through the year because there’s always something going on, like… there were deadlines that changed and even once we had one of our lecturers just leave. I think she went overseas. I am not sure, but [redacted] contacted us to make sure we were okay and let us know what the plan was. So, definitely, the PST is important all the time because anything could happen, and you would need to know.

These comments support the findings of Botha (2014, p. 244) who suggests adult learners are “usually fairly sophisticated and independent; thus, possessing the capacity to act independently” and be more self-directed than their younger peers. She explains adult self-directedness as the “capacity to pre-emptively be an active agent in one’s own learning and growth.”

Throughout our engagement with the participants, all the PSTs were spoken of in a manner that was clearly appreciative. However, 26 of the 34 participants did not indicate any understanding of a direct link between the support they received and their emotional well-being as distance students. We found this apparent misalignment between intent and perception interesting. After identifying this misalignment, we paused to consider whether the affective aspect of the PST role may need to be more explicitly described to ODL students, or whether instead the PST role may need to be reviewed to intentionally make the support provided more generic in its scope.

The aim of this study was to determine what value ODL students place on having an online presence dedicated to their emotional well-being. As a means of negating the sense of isolation so often reported by students studying in an online mode, an affective presence, in the form of a PST, was introduced into the ODL model of a South African PHEI. Data collected during this study strongly suggested that, although each of the participants was familiar with who their PST was (or had been), there was not a shared or common understanding of the role as being intentionally affective in nature. Although nine of the participants shared that they had, at least to some extent, experienced the role as emotionally supportive, the remaining 25 tended to view the PST role as far more generic. Although certain participants, particularly those who were slightly younger, viewed this support as essential, others considered the role a welcome addition to their learning journey rather than a support of critical importance.

In light of these findings, we initially planned to recommend that the institution’s distance team make a more structured and intentional effort to explain the PST role to new and existing students. In addition, we considered recommending that the PSTs become more proactive in explaining their role to students, including the nature of the support they provide. However, after considering the findings further, we believe there is greater merit in flipping this approach. Rather than more clearly explaining the PST role, we suggest using the input from the participants to adapt the PST role to more closely align with the needs and expectations of the students for whom this role was created. As noted, very few participants understood the PST role as being purely affective in nature. Despite the small number of references to appreciating the support received from their PST because it relieved their anxiety about something or resolved an issue of a more personal nature, very few participants articulated any real understanding of the PST role as it was envisaged by the institution.

As a result, our recommendation is that the institution in question, as well as any other institution which may be considering such a role within their ODL model, embrace this perception of the PST and allow the role to become more intentionally structured as a generic support mechanism. However, the revised PST role should not exclude the affective component as endorsed by Tait (2000, 2014), but rather it should add to it. We believe that Karp’s (2011) four non-academic support mechanisms, as noted earlier in this paper, can be used as the framework on which to build the PST role in its next iteration. We also appreciate that the suggestion of matching support to students’ needs is hardly ground-breaking.

We stand firm in our belief that the presence of a dedicated role, outside of peer or facilitator support, can have significant value if closely and intentionally tailored to the needs of distance students. The PST role helps distance students by implementing Karp’s (2011) non-academic support mechanisms:

In closing, we acknowledge that this is an exploratory study with some limitations. First, this study was conducted with one cohort of students before and during the pandemic. It will be interesting to do follow-up research in a post-pandemic era. Second, this study did not consider the age, ethnicity, geographical location, or other socio-cultural factors of the students. The purpose of this study was to determine the value ODL students in general place on a dedicated support mechanism focused on ensuring their emotional well-being. We acknowledge that follow-up research is needed to determine if and how socio-cultural factors affect students’ views.

Regardless of how the PST role is understood or used by students, we believe this study reaffirms the value of having a dedicated support mechanism in place. The next iteration of the PST role may be more generic, but that will not be to the exclusion of affective support. The generic nature of the PST role does not eliminate affective support; it adds to it.

The four steps of the Summary of the Programme Success Tutor (middle circle) are described as follows:

The conceptual framework of the Targeted and Tailored Student Supports study are described as follows:

The four inter-relational student support mechanisms proposed by Karp (2011) are described as follows:

The confirmable outcomes of the PST Role as the provider of affective care all lead to improved student experiences and are described as follows:

Action 1: Retain the role, improve the role or apply the role to other ODL models which leads to improved student experiences.

Action 2: Modify the role, do away with the role, or seek viable alternatives that students deem necessary, which leads to improved student experiences.

Akhter, R., & Sumi, F. R. (2014, January). Socio-cultural factors influencing entrepreneurial activities: A study on Bangladesh. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 16(9), 1–10. http://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jbm/papers/Vol16-issue9/Version-2/A016920110.pdf

Angelino, L. M., Williams, F. K., & Navtig, D. (2009, July). Strategies to engage online students and reduce attrition rates. The Journal of Educators Online, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.9743/JEO.2009.1.4

Arghode, V. (2012). Qualitative and quantitative research: Paradigmatic differences. Global Education Journal, 2012(4).

Barrett, E., & Lally, V. (2000, April). Meeting new challenges in educational research training: The signposts for educational research CD-ROM. British Research Journal, 26(2), 271–290. https://www.jstor.org/stable/i266408

Bean, J. P., & Metzner, B. S. (1985, Winter). A conceptual model of non-traditional undergraduate student attrition. Review of Educational Research, 55(4), 485–540. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170245

Bensimon, E. M. (2007, Summer). The underestimated significance of practitioner knowledge in the scholarship on student success. The Review of Higher Education, 30(4), 441–469. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2007.0032

Bharuthram, S. (2018). Attending to the affective: Exploring first year students’ emotional experiences at university. South African Journal of Higher Education, 32(2), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.20853/32-2-2113

Bitsch, V. (2005). Qualitative research: A grounded theory example and evaluation criteria. Journal of Agribusiness, 23(345-2016-15096), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.59612

Botha, J. (2014). The relationship between adult learner self-directedness and employability attributes: An open distance learning perspective [Unpublished master’s dissertation]. University of South Africa. https://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/13598

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2.) Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

Brookfield, S. (2006). The skillful teacher: On technique, trust and responsiveness in the classroom. Jossey-Bass.

Burns, D., Dagnall, N., & Holt, M. (2020, October 14). Assessing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student wellbeing at universities in the United Kingdom: A conceptual analysis. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 5, p. 582882). Frontiers Media SA. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.582882

Carey, J. (2011). Johnne Donne: Life, mind and art. Faber & Faber.

Chase, J. A. (2010). The additive effects of values clarification training to an online goal-setting procedure on measures of student retention and performance [Doctoral Dissertation]. University of Nevada, Reno.

Christie, H., Tett, L., Cree, V. E., Hounsell, J., & McCune, V. (2008, October 10). A real rollercoaster of confidence and emotions: Learning to be a university student. Studies in Higher Education, 33(5), 567–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802373040

Cleveland-Innes, M., & Campbell, P. (2012). Emotional presence, learning, and the online environment. The International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 13(4), 269–292. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i4.1234

Cobb, S. C. (2009). Social presence and online learning: A current view from a research perspective. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 8(3), 241–254. https://www.ncolr.org/jiol/issues/pdf/8.3.4.pdf

Creswell, J. W. (2021). A concise introduction to mixed methods research (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Damasio, A. (1999). The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. Harcourt.

Davidson, C., & Wilson, K. (2013, December 9). Reassessing Tinto’s concept of social and academic integration in student retention. Journal of College Student Retention: Research Theory & Practice, 15(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.2190/CS.15.3.b

Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (2011). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. SAGE.

Dirkx, J. M. (2008, December 16). The meaning and role of emotions in adult learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 120, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.311

Fynn, A., & Janse van Vuuren, H. (2017). Investigating the role of non-academic support systems of students completing a master's degree in open, distance and e-learning. Perspectives in Education, 35(1), pp.189-199. https://doi.org/10.18820/2519593Xpie.v35i1.14

Gill, P., Stewart, K., Treasure, E., & Chadwick, B. (2008, March 22). Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal, 204(6), 291–295. https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.192

Grubb, W. N. (2006). Like, what do I do now? The dilemmas of guidance counseling. In T. Bailey and V. S. Morest (Eds.), Defending the community college equity agenda (pp. 195–222). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hancock, D. R., & Algozzine, B. (2017). Doing case study research: A practical guide for beginning researchers. Teachers College Press.

Kääriäinen, M., Mikkonen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2020). Instrument development based on content analysis. In H. Kyngas, M. Kristin, & M. Kaariainen (Eds.), The application of content analysis in nursing science research. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-30199-6

Kahu, E. R., Stephens, C., Leach, L., & Zepke, N. (2013, June 24). The engagement of mature distance students. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(5), 791–804. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/07294360.2013.777036

Karp, M. M. (2011). Towards a new understanding of non-academic student support: Four mechanisms encouraging positive student outcomes in the community college. Columbia University Working Paper 28. http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/178542

Kaufmann, R., & Vallade, J. I. (2020, April 10). Exploring connections in the online learning environment: Student perceptions of rapport, climate, and loneliness. Interactive Learning Environments, (30:10), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1749670

Kim, H. S., & Sasaki, J. Y. (2012, December 2). Emotion regulation: The interplay of culture and genes. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(12), 865–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12003

LeDoux, J. (1999). The emotional brain: The mysterious underpinnings of emotional life. Phoenix.

Lee, Y., Choi, J., & Kim, T. (2013, March). Discriminating factors between completers of and dropouts from online learning courses. British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(2), 328–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01306.x

LaPadula, M. (2003). A comprehensive look at online student support services for distance learners. American Journal of Distance Education, 17(2), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15389286AJDE1702_4

Lehman, R. M., & Conceição, S. C. (2010). Creating a sense of presence in online teaching: How to "be there" for distance learners (Vol. 18). John Wiley & Sons.

Lincoln, Y.S., & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage

Lipman, M. (2003). Thinking in education (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Makhanya, M., Mays, T., & Ryan, P. (2013). Beyond access: Tailoring ODL provision to advance social justice and development. South African Journal of Higher Education, 27(6), 1384–1400. https://doi.org/10.20853/27-6-305

Matizirofa, L., Soyizwapi, L., Siwela, A., & Khosie, M. (2021, September 6). Maintaining student engagement: The digital shift during the coronavirus pandemic a case of the library at the University of Pretoria. New Review of Academic Librarianship, 27(3), 364–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614533.2021.1976234

Mortiboys, A. (2012). Teaching with emotional intelligence. A step by step guide for higher and further education professionals (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Netanda, R. S., Mamabolo, J., & Thename, M. (2019, September 19). Do or die: Student support interventions for the survival of distance education institutions in a competitive higher education system. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 397–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1378632

O’Regan, K. (2003, September). Emotion and e-learning. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network, 7(3), 78–92. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v7i3.1847

Park, C. L., Perry, B., & Edwards, M. (2011, March 3). Minimising attrition: Strategies for assisting students who are at risk of withdrawal. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 48(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2010.543769

Pekrun, R., & Stephens, E. (2010). Achievement emotions in higher education. In J. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (25th ed., pp. 257–306). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-8598-6_7

Plutchik, R. (2003). Emotions and life: Perspectives from psychology, biology, and evolution. American Psychological Association.

Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2012, August 8). Gender bias undermines evidence on gender and health. Qualitative Health Research, 22(9), 1298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732312453772

Robertson, S. G. (2020). Factors that influence students’ decision to drop out of an online business course [Doctoral dissertation, Walden University].

Rotar, O. (2022, January 6). Online student support: A framework for embedding support interventions into the online learning cycle. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 17(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41039-021-00178-4

Rovai, A., Ponton, M., Wighting, M., & Baker, J. (2007, July). A comparative analysis of student motivation in traditional classroom and e-learning courses. International Journal on E-Learning, 6(3), 413–432. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/20022/"

Rumble, G. (2000, January). Student support in distance education in the 21st century: Learning from service management. Distance Education, 21(2) 216–235. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/0158791000210202

Ryan, Y. (2004). Pushing the boundaries with online learner support. In J. Brindley, C. Walti, & O. Zawacki-Richter (Eds.), Learner support in open, distance and online learning environments (pp. 125–134). Bibliotheks und Informations system der Universität Oldenburg. https://acuresearchbank.acu.edu.au/item/8q9wz/pushing-the-boundaries-with-online-learner-support

Shea, P. (2006). A study of students' sense of learning community in online environments. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v10i1.1774

Shikulo, L., & Lekhetho, M. (2020). Exploring student support services of a distance learning centre at a Namibian university. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1737401

Solomon, R. C. 2008. True to our feelings: What emotions are really telling us. Oxford University Press.

Stets, J. E., & Turner, J. H. (2006). Handbook of the sociology of emotions. Springer.

Tait, A. (2000). Planning student support for open and distance learning. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and E-learning, 15(3), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/713688410

Tait, A. (2004). On institutional models and concepts of student support services: The case of the open university UK. 3rd EDEN Research Workshop, Oldenburg. http://www.c3l.uni-oldenburg.de/cde/support/fa04/Vol.%209%20chapters/KeynoteTait.pdf

Tait, A. (2014, February). From place to virtual space: Reconfiguring student support for distance and e-learning in the digital age. Open Praxis, 6(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/ 10.5944/openpraxis.6.1.102

The Independent Institute of Education 007. (2020). PDIIIE007: Research and postgraduate studies process and procedure. https://irp.cdn-website.com/3f7b6868/files/uploaded/PDIIE007%20Research%20and%20Postgraduate%20Studies%20Process%20and%20Procedure%202022%20Reupload.pdf

Thorpe, M. (2002). Rethinking learner support: The challenge of collaborative online learning. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 17(2), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680510220146887a

Tobin, G. A., & Begley, C. M. (2004, October 21). Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 48(4), 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03207.x

Visser, M., & Law-van Wyk, E. (2021, May 3). University students mental health and emotional wellbeing during the Covid-19 pandemic and ensuing lockdown. South African Journal of Psychology, 51(2), 229243. https://doi.org/10.1177/00812463211012219

Waight, E., & Giordano, A. (2018, May). Doctoral students' access to non-academic support for mental health. Journal of Higher Education Policy & Management, 40(4), 390–412. https:/doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2018.1478613

Weiss, R. E. (2000, December). Humanizing the online classroom. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2000(84), 47–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.847

Williams, L. S. (2017, May). The managed heart: Adult learners and emotional presence online. Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 65(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/07377363.2017.1320204

Wosnitza, M., & Volet, S. (2005, October). Origin, direction and impact of emotions in social online learning. Learning and Instruction, 15(5), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.009

You, J., & Kang, M. (2014, August). The role of academic emotions in the relationship between perceived academic control and self-regulated learning in online learning. Computers and Education, 77, 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.04.018

Zembylas, M. (2008, May 9). Adult learners' emotions in online learning. Distance Education, 29(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910802004852

Zembylas, M., Theodorou, M., & Pavalakis, A. (2008, June 6). The role of emotions in the experience of online learning: Challenges and opportunities. Educational Media International, 45(2), 107–117. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523980802107237

Liesl Scheepers is the Manager of Online Teaching and Learning at the Independent Institute of Education’s Varsity College Online Centre, South Africa, and a current PhD student at the University of South Africa (UNISA). Her research focuses on emotional wellness, teacher self-efficacy, and burnout in an ODL context. She is currently in the process of completing her PhD, under the supervision of Professor Geesje van den Berg.

Email:lscheepers@varsitycollege.co.za

Geesje van den Berg is a full Professor in the Department of Curriculum and Instructional Studies at the University of South Africa (UNISA). Her research focuses on student interaction, academic capacity building, social justice, and the use of technology in ODL. She has published widely as a sole author and co-author with colleagues and students in curriculum studies and Open Distance Learning (ODL). Her work appears as papers and book chapters in local and international scientific journals and books. Geesje van den Berg is leading a collaborative project between Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg University in Germany and UNISA, involving academic capacity building for UNISA academics in ODL. Currently, she is Program Manager of the structured Master’s in Education (ODL) and teaches two modules in the program. Numerous master's and doctoral students have completed their studies under her supervision.

Email:vdberg@unisa.ac.za

The Programme Success Tutor (PST) role will serve as the case-study for this exploratory research. The focus of this qualitative study will be to answer the following main question:

What inherent value is there in intentionally establishing an online presence dedicated to student emotional wellness, particularly during times of crisis?

Number: __________________ Current Year of Study: __________________ Qualification: __________________

In light of the discussion and exchange generated by the 10 questions that have been posed, would you vote to:

![]() This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.