VOL. 15, No. 2, 97-112

This fictional case is presented to facilitate discussion of the pros and cons of shared distance education. The key premise concerns whether a syndicate of colleges and universities should collectively offer courses and programs rather than single institutions doing it alone. It describes a number of current efforts and outlines a model to explain the relative lack of sharing. Potential success factors derived from the realm of electronic commerce are presented as a guide for such an effort. The question remaining for students and others is what the pedagogical and business plan should be for a shared distance education initiative.

Ce cas fictif est présenté afin de faciliter la discussion entre les pour et les contre du partenariat en formation à distance. L'enjeu principal consiste à savoir si un regroupement de collèges et d'universités devraient offrir collectivement des cours et des programmes plutôt que de le faire sur une base individuelle. Cet article fait état de certaines expériences en cours et propose un modèle pour expliquer l'absence relative de partenariat. Des facteurs de succès inspirés du commerce électronique sont proposés afin de mieux supporter les efforts de partenariat en formation à distance. Ce qui reste à élaborer, pour les étudiants et les autres acteurs du domaine, sont des plans d'affaire et une planification pédagogique pour le succès d'une telle entreprise.

Professor Arnold Hodgson had spent most of his academic career at North Coast University (NCU). He was currently a senior tenured professor in the Marketing Department. His specialty was consumer behavior. In the last several years he and many of his colleagues at NCU and elsewhere had become interested in electronic commerce. Clearly there was a major dimension of consumer behavior in all business to customer transactions on the Internet. Hodgson had written several papers in this area and was quite pleased when his colleagues told him they were useful contributions.

Of late, however, Hodgson had come to the conclusion that his students could benefit from what electronic commerce had to offer in addition to just learning about it. In particular he believed that distance education via the Internet would be a useful and effective way to offer his fourth-year course on consumer behavior (CBEH 407). He had always used technology in his lectures and was comfortable creating PowerPoint presentations and communicating with his students via e-mail. He also had a basic Web site for his course.

This was all well and good, but he believed it was not nearly enough. More significantly, he realized he was not alone in thinking about the benefits of distance education. Many of his colleagues in other departments and other universities were coming to the same conclusion. They should develop a fuller presence for their courses on the Web. Where Hodgson differed from them was that he strongly believed they should share their efforts. Why should he develop a distance version of CBEH 407 when he knew that more than a dozen of his colleagues at other institutions were planning to do the same thing? Or conversely, why should they do it when he was doing it? He believed that they should all share and cooperate in this venture and produce a better offering than any of them could do alone. What could be simpler? This is what academics had been doing with textbooks for decades. They did not write their own text, but adopted the best books they could find from those written by their fellow academics.

Hundreds of programs exist worldwide. Many are excellent, many offer similar courses and approaches, and the result is duplication of content and variable quality. It makes sense to collapse these offerings into a smaller number of excellent syndicates where duplication would be minimized and the course would be the best offering possible. Of course, there should always be multiple syndicates as new approaches evolve. Experimenting with different approaches would always be necessary for continual improvement in education.

Hodgson ultimately envisaged that students would subscribe to such programs rather than registering for a degree. By so doing they could take a course when they needed it and would have the opportunity to take it again in the future if there was significant change in content or need for the material. This would be true just-in-time learning. Not all courses would be offered in this way, but with a syndicate’s shared courses offered at a distance, students would have the flexibility not only to take courses when and where they wanted, but to get content that was unavailable at their home institution.

He soon realized that this altruistic approach was fraught with problems. Of all the people he knew in consumer behavior—at least 200 of whom he frequently saw at conferences—only one at a distant college in South Africa expressed any interest in his shared approach. His colleagues had different reasons for declining, but most seemed to believe that their own consumer behavior offerings—whether in person or on the Web—were probably better than anyone else’s. They did not say this directly and often referred to the relevance of their perspectives, the emphasis they gave to different topics, the particular readings they assigned, the “downtown” projects and marketing simulations they used, or the presentations by unique guest speakers.

Hodgson was not deterred; he probed a number of his colleagues and discussed his plans with his department head and his dean. It soon became clear that for a large number of other reasons people and institutions did not wish to share courses and partake in a syndication of offerings. He started to develop a model to incorporate these variables. And he believed that his model must go beyond simply determining attitudes toward distance education. He had already seen Ross and Klug’s (1999) findings, which indicated that business college faculty and administrators were more receptive and supportive of distance education if they had more experience with it, had fewer difficulties with it, and believed it fitted with their institution.

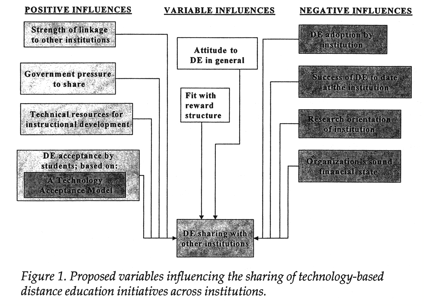

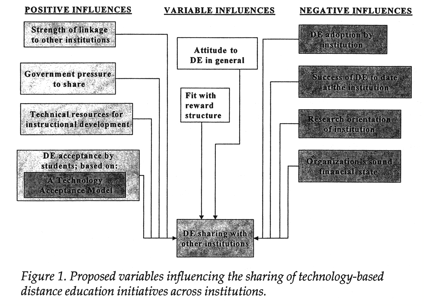

However, on reflecting on this study he realized that motivating one institution to adopt distance education was probably not the same as encouraging it across institutions. As he worked on his model, he found that many of the reasons offered for not sharing had nothing to do with successful or unsuccessful teaching of an actual course (in person or at a distance). They were about the politics and financial viability of departments—and the business schools and faculties in which they resided. His current model can be seen in Figure 1.

He categorized the independent variables into three groups: those that he believed would promote shared distance education, those that would stifle it, and those that might or might not facilitate it depending on their values. Because he had seen no real sharing, he did not attempt to refine sharing as a dependent variable yet. He knew that the whole area of performance indicators in distance education had been found to be complex (Shale & Gomes, 1997); probably several measures of sharing success would be required.

His basic theory was that the better off the institution was on its own (as to research and funding), the less willing it would be to get involved with distance education, sharing, and syndication with other institutions. He also hypothesized that the more successful a university or college had been with distance education to date, the less it would wish to get involved with other institutions even though it was in favor of distance education itself. Who would want to share a potentially profitable revenue stream? Everyone has tight budgets.

With regard to the technical aspects of distance education, he postulated a positive relationship between available resources and sharing. If you have the resources, there may be synergies and advantages to working with others. As well, if students at the institution like the existing distance education, it is more likely that sharing will work (because the institution is good at distance education, even though they might not wish to share with other institutions). He also believed that a detailed model of technology acceptance should be used to guide the acceptance and use of the involved technologies and interfaces (Davis, Bagozzi, & Warshaw, 1989).

He believed that the creation of the Canadian Virtual University (http://www.cvu-uvc.ca), which he had read about in the Chronicle of Higher Education (“7 institutions form Canadian virtual university,” 2000), offered support for his model. Although this group of seven Canadian universities did promote sharing of courses among all its members, he did not consider any of them to be among Canada’s major research institutions, thus confirming his view that a strong research orientation could minimize pressures to share distance education courses.

His discussions with colleagues also made him keenly aware that there were several important variable effects to consider. A positive attitude toward its benefits and value will lead to distance education and potentially encourage sharing, at least at the level of individual faculty members; a negative attitude will have the reverse effect. A supportive reward structure is needed to facilitate distance education in general. Clearly faculty will not develop and share distance offerings if they receive no annual merit increments for doing so. He also realized that more than extrinsic rewards were involved. He noted that Wolcott and Betts (1999) found that intrinsic rewards (such as learning about new technology) to be a major motivator to the use of distance education. It was also no surprise that they found that continued involvement in distance education was affected by extrinsic factors such as technical support and increased salary.

Realizing his overall theoretical framework would be a difficult model to test more than anecdotally, he set about trying to learn more about distance education and started investigating what strategic alliances might already exist. Had anyone already succeeded at syndication? From the numerous electronic news feeds he regularly received (e.g., NewsScan (http://www.newsscan.com/, March 2, 2000) and Edupage (http://www.educause.edu/pub/edupage/edupage.html, March 2, 2000) he learned of a number of initiatives.

He dug out more information on these using both the Web and as many traditional sources as he could find. The following activities and initiatives emerged.

At an initial examination, Universitas 21 (http://www.universitas.edu.au/, February 24, 2000) already appeared to being doing syndication. They were a loose international organization of nearly 20 universities intending to cooperate in a number of venues. However, they seemed more oriented to research and to date had not announced any collaborative efforts in distance education. They did suggest that they would be dealing with teaching and learning technologies, however. Possibly they might be the right group to support distance doctoral programs should a viable model be found for them. However, he wondered what Robert Murdoch’s News Corporation’s recent agreement with Universitas 21 to offer online courses would mean (“NewsCorp Targets Education,” 2000). Clearly Murdoch’s past efforts had focused on media, not education. Subsequently, he was not surprised to see that these plans to work with Murdoch’s corporation had been abandoned—although Universitas 21 was planning another corporate arrangement (Maslen (2000).

From other electronic sources (http://www.thestandard.net/ar-ticle/display/0,1151,7122,00.html, December 19, 1999) he discovered several collaborations that he thought held promise. Both UNext (http://www.unext.com/, February 28, 2000) and Pensare (http://www.pensare.com/, February 28, 2000) had assembled impressive groups of schools to produce programs.

UNext had Columbia University, Stanford University, the London School of Economics, and Carnegie-Mellon University in their camp. They even struck a new name for their Internet school, Cardean University (http://www.cardean.com/, February 28, 2000). Pensare was no less impressive, with arrangements with the Harvard Business School and the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. On digging further he saw that these were driven more by private companies than from an internal push to share with fellow institutions. He was particularly concerned when he saw the Los Angeles Times report that the UNext might have Ivy League professors “lend their names and insights to UNext’s staff,” but “The people who actually run the classes are UNext employees—people the company has hired to act as online mentors, grade homework and answer student’s questions” (Huffstutter & Fields, 2000). This was certainly not his vision of the sharing that he hoped his marketing colleagues at other universities would engage in. His dismay deepened when he saw that even booksellers were getting into the act. Barnes and Noble was partnering with course developer notHarvard.com to offer free online courses that would use books sold by Barnes and Noble in a new entity called Barnes and Noble University (http://www.notharvard.com/news/pressrelease.cfm?id=5, August 3, 2000) (“Book Retailer,” 2000). He strongly believed that bookstores were supposed to serve educational institutions, not run them.

He realized that significant concerns arose when profitmaking companies formed alliances with nonprofit organizations such as universities. Universities might even lose their tax-exempt status if they became too deeply involved. He saw a host of intellectual property issues where professors who traditionally owned their materials were now confronted with significant revenue-sharing pressures given the need for the services of course developers (from within their own universities or from private companies). Few professors had the skill, time, or inclination to create a professional version of their material for the Internet. If professors—the traditional providers of course materials—did not provide these activities, someone had to be paid to do so. Things were becoming much more complicated than the textbook model where many instructors adopted the same book.

He sensed that the profit motive was all-important and that one should look at a publisher model as including more than textbooks. Other companies were identified that were putting together courses from multiple universities and drawing course authors from many universities and colleges—not necessarily those that would be recipients of the courses. University Access (http://www.universityaccess.com/, February 28, 2000) and eCollege (http://www.eCollege.com/, February 28, 2000) were just two with significant Web presences, and he saw these as becoming the modern incarnation of traditional publishers.

Next he reviewed the annotated list of schools doing distance education that was posted by the Center for Virtual Organizations and Commerce (CVOC) at Louisiana State University (http://isds.bus.lsu.edu/ cvoc/projects/virtualeducation/html/, February 24, 2000). There was no shortage of technology-based distance offerings in the United States, and initiatives in both France and Canada also appeared. He also saw at this site that the International Data Corporation was predicting that the number of distance education students would triple by 2001. With resources never plentiful, he believed this indicated that shared approaches were even more important.

So far, however, the only real conduit of sharing he had discovered was between businesses and universities. The CVOC site indicated that the Southern Methodist University was having materials produced by Fifth Gear Media Corporation, the University of Georgia was implementing a customized MBA for Price Waterhouse Coopers, and the University of Southern California and the Caliber Learning Network were investigating the joint development of an executive MBA. And despite its initial consortium with several Ivy League schools, Pensare was licensing a complete MBA program from the Fuqua School at Duke University.

Drilling down further he did identify three university-only sharing arrangements:

The first two were not the kind of sharing he envisaged. The Tuck-Japan alliance seemed fairly one-way with Tuck offering a program for Japanese executives. The C-MU-Columbia partnership was only for a certificate program in information resource management. However, the third partnership appeared more promising. It involved the creation of technology-enabled courses that would be delivered beyond these two institutions in their different countries.

More recently he saw Edupage reporting that the business students at the universities of Virginia, Michigan, and California-Berkeley were to be given the opportunity to take online courses at each other’s institutions, following the success of Michigan students in online programs taken from abroad (Edupage, 2000, June). He was concerned, however, that expensive videoconferencing appeared to be playing a major role in this initiative. Thus he was not surprised to learn that the Ivey Business School at the University of Western Ontario had just decided to cancel its videoconference-based executive MBA program (P.D. Carr, personal communication, October 26, 2000.

He then discovered R1, a true portal for distance education offerings (http://www.R1edu.org/, March 14, 2000). Hosted by the University of Washington, R1 was a loose organization of members of the Research I division of the Carnegie Classification of Universities (http://www.carnegiefoundation.org/AboutUs/AboutUs.htm, March 14, 2000). When he examined the R1 site, he found 27 participating universities in both the US and Canada. He searched on marketing and found 12 offerings. When he refined his search to degree offerings, this list dropped to nine, and only two or three looked like advanced marketing courses. There was nothing close to consumer behavior. Nonetheless, he believed this was promising. Here were research-oriented schools making note of what they had available in distance education. It was a start. R1 needed to go further, however, and build actual programs out of these offerings and become more proactive in promoting them as part of existing degree programs if true sharing were to become a reality. He compared R1 with the Canadian virtual university he had examined earlier and thought they were both making sharing possible, but that neither was significantly involved in real sharing—any more than traditional schools were when they allowed students to transfer courses between institutions. There was still duplication of courses and no systematic syndication.

On a different dimension he realized that if whole courses and programs were not being readily shared, some interesting success was being achieved by students collaborating on projects across universities. A number of professors had recently started their students working on projects about enterprise resource planning with students at other institutions in different continents (Rosemann, Scott, & Watson, 2000). It certainly seemed that they would gain a richer appreciation of issues than would be possible with just one professor in one classroom, although some communication issues were still to be worked out. Hodgson wondered if students rather than instructors might might ultimately instigate sharing. Still, he wanted to find a whole course from one institution that could be used at many others.

Finally, he discovered a consumer behavior course that was offered not only over the Internet, but was listed as part of many university offerings. World Lecture Hall (http://www.utexas.edu/world/lecture/index.html, March 17, 2000) maintained by the University of Texas at Austin appeared to concentrate almost exclusively on university-level courses. Moreover, their list seemed to be growing significantly. As of March 2000, their “What’s New” list (http://wnt.cc.utexas.edu/~ccdv543/wlh/ wlhnew1.cfm, March 17, 2000) had added 48 approved new course links in the past 60 days. When he searched in marketing (http:// www.utexas.edu/world/lecture/mkt/, March 17, 2000), he found three consumer behavior courses. One link was dead and one was just a Web page for a classroom course, but the third, at Southern Illinois University (http://www.siu.edu/departments/coba/mktg/courses/mktg305/, March 17, 2000), could be registered for immediately, either for credit or not. Fees were even listed: US$1,234 for the credit version and US$999 for the noncredit version. Fees could be paid by credit card. This seemed to be what he was thinking about, except that it did not seem to have much of a real-time component: no student discussion groups. However, the description did indicate that e-mail would be promptly answered by the instructor, who also posted weekly overview announcements. Two CD/ROMs were provided, along with a text and access to a special Web page (restricted to registered students). On balance Hodgson had to admit it seemed solid and was as comprehensive as his own offering. A student taking this course would probably be recommended for transferred credit at North Coast.

His search continued. He also saw that success was not simple, even with existing distance offerings. Not all initiatives were being received positively. Jones University International, a Web-based university, caused concern among the American Association of University Professors when it was accredited (McCollom, 1999). Western Governors University had been called into question by allowing degrees based on the results of standardized tests (Young, 1999).

In conclusion, Hodgson saw many approaches, but no conclusive answer as to how a sharing approach should be designed or how to forge links with other institutions. Change would be difficult, but he believed it was essential. He found Ives’ (2000) representation of the disruptive potential of technological change in management education particularly compelling (http://isds.bus.lsu.edu/cvoc/talks/edu4_99.ppt, March 1, 2000). Figure 2, from Ives’ presentation at the Center for Virtual Organizations and Commerce, clearly suggests that it was not a question of if technology based education would become essential, but when. Ives suggested not only that academics hoped to offer higher quality education than students expected, but also—and more important—that the trend in quality of distance education was increasing, whereas traditional approaches (however good) were unchanging and hence not improving.

Similarly, he saw Drucker (Lenzner & Johnson, 1997) predicting related changes several years earlier:

Thirty years from now the big university campuses will be relics. Universities won’t survive. It’s as large a change as when we first got the printed book. Do you realize that the cost of higher education has risen as fast as the cost of health care? ... Such totally uncontrollable expenditures, without any visible improvement in either the content or the quality of education, means that the system is rapidly becoming untenable.... Already we are beginning to deliver more lectures and classes off campus via satellite or two-way video at a fraction of the cost. The college won’t survive as a residential institution.

Although Hodgson saw that organizational issues were by far the greatest hurdle in implementing his vision of sharing, he realized that a solid technology platform was also essential. He examined a range of possibilities that suggested many questions.

As he started to formulate his questions, he realized that perhaps he should return to his model and consider other success factors for his electronic commerce initiative in education. To be successful it must be approached systematically.

Hodgson really believed his model (Figure 1) had much to offer, but as he had not formulated a research design to test it, he had to admit he was uneasy in using it as his only guide in determining how he should proceed. After all, this was an electronic commerce venture, and there were available numerous lists of success factors for these. The list he finally turned to was from a recent case book in electronic commerce (Huff, Wade, Parent, Schneberger, & Newson, 2000). He reasoned that factors arising from a variety of cases would be a more comprehensive than those from a single company or specific industry.

He examined these carefully and tried to think of the issues in distance education that would come to bear on each. His list for each of the critical success factors from this book included numerous considerations as follows.

Added value. This was the whole point of his initiative. It must be convenient for students and faculty and provide something that was not already available—or improve what was available. He believed students might take to it more easily than some of his colleagues. Students demanded flexibility and were frequently moving and changing jobs. They would welcome being able to take some of their courses in the distance mode.

He also believed his approach would add value by offering quality and the same vetting as courses that were offered in the classroom—as well as providing a product that competed on price and choice. Students could select distance or classroom offerings based on their needs. He certainly did not want to force them all to go the distance route any more than he believed all instruction needed be done face to face.

In particular, he believed choice could be a major driver of his initiative. He knew NCU could not offer all courses in all disciplines, but if they could provide students with offerings from sister institutions in fields where NCU was not strong, they could strengthen their programs. He was already considering offering a well-regarded advertising course at a nearby urban university knowing that his small Marketing Department would benefit if he could make it available to his students.

Niche focus. Here again Hodgson believed he had the right approach. He believed he was correct not to offer all courses in all programs to all students. He could start with a group of marketing courses at NCU. He thought he might be able to persuade his own Accounting Department to have its students take other institutions’ financial accounting courses. He certainly knew they were chronically understaffed and might welcome this opportunity to obtain quality courses for their majors without increasing staff. To Hodgson, starting small like this seemed the right niche.

Flexibility. If he went ahead expecting things to change and evolve, he should be all right. He must alert those who would review his proposal that he would probably return every year with changes. He felt good about this as he knew that to succeed, his initiative must improve continually. He only hoped he could convince other academics (especially senior colleagues at other institutions) that things would always be in a state of flux.

Geographical segmentation. Hodgson puzzled over this factor. Wasn’t one of the strengths of distance education its ability to be taken anywhere in the world? This was certainly the ultimate extension of his vision. He did start to realize, however, as he drew on his own marketing background, that this would not be easy. Even if distance education was done asynchronously across times zones, one still had to consider support calls. And what about language? Many international students could read and write English, but sometimes speaking was difficult, so telephone support would be dificult, and local support would have to be carefully implemented. International partnering was appealing, but it seemed best to start regionally. It was tempting to consider extending his approach to the Asian initiative, which his dean had mentioned. Should he follow this avenue for his fledgling initiative (it would provide funding), or would this spread resources too thin and lead to failure?

Appropriate technology. As Hodgson had already concluded, technology was probably the least of his concerns. It had to be right, and it had to be managed and maintained, but one did not have to negotiate with a server to host a database or present Web pages. He also had the advantage that infrastructure was in place at NCU and at any other prospective partnering educational institution. Security and scalability would have to be considered, but with small beginnings and demonstrated success, these could be enhanced at NCU and elsewhere. He did not believe a successful project would have difficulty justifying expanded technology. Provincial and state governments liked to do this if they were presented with a clear plan with a track record.

Managed perceptions. North Coast was a well-established and respected regional university. Although it had some international connections, its strong suit was attracting local students and those from adjacent states and provinces. It had a good brand, but it was not particularly strong and certainly not well known beyond the region. So Hodgson knew that he must get it right: a poor distance effort would do more harm than good and preclude any further initiatives for some time. He knew of several nationally renowned universities and some similar regional institutions in his area. He believed that students’ and others’ perceptions of his shared initiative would depend on carefully cultivating and developing relationships with someone from both of these camps. He was not sure where to start. Should it be one major school (perhaps hard to convince) or several adjacent regional institutions? Perhaps his model could help him make a selection.

Hodgson felt good about the trust and presence issues involved in perceptions. NCU had been in existence for 74 years and was well accepted. It also had an attractive campus, or “physical presence,” which would help prospective students put a “face” to what was likely to be a faceless operation in many ways.

Exceptional customer service. This was a major budget item in his proposal. Students must be able to discuss problems with staff and faculty. E-mail and discussion groups were good, but at a minimum telephone contact would also be essential, especially for complex questions and technology problems. This would be particularly important at first as they all learned how to proceed. Perhaps in the second year they would develop approaches and a list of frequently asked questions that could be posted online.

Effective connectedness. Hodgson had taught in executive education seminars, and he knew the camaraderie that could be developed in even a short week of close personal contact. He believed that there should be elements of personal contact in any distance offering. Students should come to campus for some classes, and maybe the campus could go to the students or hold some courses in premier tourist destinations. Building personal contacts could also promote the idea of subscription rather than registration. Perhaps he was a true marketer, as he believed that students should still be drawn to NCU and other institutions after graduation. His approach here was to build connections both electronically and in person and have each reinforce the other. He knew he would receive support for this approach from his colleagues in continuing education who were always talking about lifelong learning.

Understanding the Internet culture. Hodgson had taken his first computer course as an undergraduate when programming was done on punched cards and he was lucky to get one run a day of a FORTRAN program. Although he had a good knowledge of present-day hardware and software, he was continually amazed how quickly things changed and how impossible it was to keep up with everything. He had just learned of the Napster program, which allowed students to download and share music with ease. He had never tried it, but he was sensitive to the sudden pervasiveness of such technologies—and how quickly they could disappear. He had just witnessed the demise of PointCast’s online news dissemination and believed he must continue to be a “netizen” and explore all aspects of new technology. He was glad that Ebay (http://www.ebay.com/, March 17, 2000) had more than 30 good-looking computer chairs as he would be spending more time at both his home and office machines.

After considerable study and review of these activities and findings, Hodgson finally believed that he had a viable plan for the development and implementation of shared distance education. It would be spearheaded by NCU, but not as the sole institution with a significant involvement. He believed his approach was both educationally sound and financially viable and was ready to present it to NCU’s Academic Program Review Committee (APRC). APRC was the university-wide body at NCU that vetted all program proposals before sending them to the University Council for final approval.

He could not be sure how they would receive it. Although NCU wished to continue to receive government sanction and accreditation, it could not expect any government funding for new programs, even those with a major technology component. Initially, it must depend solely on tuition revenues and course presentation fees. Students would either pay NCU directly for courses they took, or NCU would syndicate courses from other institutions in a cost-sharing arrangement. Of course, he hoped to attract many other institutions to commit to a similar scheme, but first he had to convince his own. He already knew NCU’s Computer Centre Director (and many other university IT officials) ranked distance education as the largest emerging issue they faced (“EDUCAUSE Survey,” 2000).

APRC would review his plan: they would wonder if the risks were acceptable—even to commit minimal resources. Was this something to which they would wish to tie NCU’s future? Would they maintain their colleagues’ respect with a major abandonment of the physical classroom? Would they succeed financially? Perhaps they would even be concerned about the security of their jobs given that some courses might become available from other universities.

As Hodgson was about to reread his plan one last time, the door to the APRC conference room opened, and his long time colleague and the chair of APRC, Fred Richardson in Anthropology, said, “Hi, Arnie, do come in. Let’s see if this distance education idea of yours makes sense.”

The basic question from this case is What should Hodgson’s plan contain and how should it be implemented? What is the educational and business case for shared distance education? How can it be achieved?

Drawing on the references in this case and any other sources you wish, you should create a plan. It should address both the pedagogy of distance education and the financial rationale. As to pedagogy, you should consider appropriate Internet-based offering methods and approaches as well as whether all of the courses should be offered in a distance venue. Related to financial success, you should determine the cost of resources (including instructional staff, hardware and software, administration, and support) and develop a revenue model. A spread sheet would be the appropriate vehicle for this so that what-if analyses can be done with a varying number of courses, different costs, and different revenue projections. Be especially sensitive to how costs and revenues would be shared among participating institutions. Consider too how the initiative would be rolled out. Would it be best done all at once? Should it be tried with just a single course? Or is a middle ground more appropriate?

In this case the author does not intend to indicate or represent either the effective or ineffective handling of any educational or business situation. This material is provided solely to stimulate discussion. North Coast University and its staff are purely fictitious. Any resemblance to specific institutions or individuals is not intended.

Book retailer to create online university. (2000, June). CAUT Bulletin, p. 3.

Davis, F.D., Bagozzi, R.P., & Warshaw, P.R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35, 982-1003.

EDUCAUSE Survey in the Chronicle of Higher Education. (2000, August 4). Edupage.

Edupage. (2000, July 3). Report on an article in Wired News of June 29, 2000.

Huff, S.L., Wade, M., Parent, M., Schneberger, S., & Newson, P. (2000). Cases in electronic commerce. Boston, MA: Irwin McGraw-Hill.

Huffstutter, P.J., & Fields, R. (2000, March 3). A virtual revolution in teaching. Los Angeles Times, Home edition, p A-1. (http://www.latimes.com/archives/, March 7, 2000).

Lenzner, R., & Johnson, S. S. (1997, March 10). Seeing things as they really are. Forbes, pp. 122-128 [Online]. Retrieved March 13, 2000 from the World Wide Web: http://proquest.umi.com/pqdweb

Maslen, G. (2000, November 7). University group abandons talks with Rupert Murdoch’s company. Chronicle of Higher Education [Online]. Available: http://chronicle.com/free/2000/11/2000110701u.htm (November 17, 2000).

McCollum, K. (1999, April 2). Accreditation under fire. Chronicle of Higher Education, p. A33.

NewsCorp targets education. (2000, June). CAUT Bulletin, p. 4.

Rosemann, M., Scott, J., & Watson, E. (2000, August). Collaborative ERP education: Experiences from a first pilot. Paper presented at the Americas conference on information systems, Long Beach.

Ross, G.J., & Klug, M.G. (1999). Attitudes of business college faculty and administrators toward distance education: A national survey. Distance Education, 20(1), 109-128.

7 institutions form Canadian virtual university. (2000, October 27). Chronicle of Higher Education [Online]. Available: http://chronicle.com (November 17, 2000).

Shale, D., & Gomes, J. (1997). Performance indicators and university distance education providers. Journal of Distance Education, 13(1), 1-20 [Online]. Available: http://cade.athabascau.ca/vol13.1/shale.html (October 26, 2000).

Wolcott, L., & Betts, K. (1999). What’s in it for me? Incentives for faculty participation in distance Education. Journal of Distance Education, 14(2), 34-49 [Online]. Available: http://cade.athabascau.ca/vol14.2/wolcott_et_al.html (October 22, 2000).

Young, J.R. (1999, May 7). A virtual user teaches himself. Chronicle of Higher Education, p. A31.

Peter Newsted is a professor of information technology management at the Centre for Innovative Management at Athabasca University. He has a doctorate from Carnegie-Mellon University and is trained in both psychology and information systems. Pete has taught at both the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and the University of Calgary and has conducted research and published on electronic communication for more than 25 years. His e-mail address is peter_newsted@mba.athabascau.ca.