VOL. 15, No. 2, 71-84

Differences in approaches to study among 89 Malaysian-Chinese, 38 Singaporean, and 65 Hong Kong university students studying in Australia are examined using Entwistle and Ramsden's (1983) Approaches to Studying Inventory. Although from a common Confucian cultural heritage background, several differences are shown among the three national groups and between male and female students. It is suggested that Rea's (1996) notion of a "reformulation" and a "challenge" approach to learning through text and experience can provide further insight into these results. Furthermore, it is shown that fixed conceptualizations of cultural characteristics can mask differences that exist between individuals and groups of individuals in a given cultural group. The characteristics of the three groups are also examined for their implications for distance educators operating with these client groups.

Les différences dans la façon d'apprendre de quatre-vingt-neuf étudiants chinois de Malaisie, de trente-huit de Singapour et de soixante de Hong-Kong, étudiants tous en Australie, sont analysés en utilisant Approaches to Studying Inventory de Entwistle et Ramsden (1983). Même si les étudiants ont tous un héritage socio-culturel confucéen commun, plusieurs différences ressortent entre ces trois groupes de nations différentes de même qu'entre les étudiants de genre masculin et féminin. Les auteurs soulignent que les concepts de Rea (1996) sur l'approche de « reformulation » et de « défis » en apprentissage par les textes et l'expérience de vie pourraient fournir de nouvelles clés d'interprétation des résultats. De plus, il est exposé que les préjugés culturels peuvent masquer des différences qui existent entre individus et groupes d'individus dans un groupe culturel donné. Les caractéristiques des trois groupes d'étudiants sont aussi examinés afin que des formateurs à distance qui travaillent avec des membres de ces groupes culturels puissent en tenir compte.

Using Entwistle and Ramsden’s (1983) Approaches to Studying Inventory (ASI), Smith, Miller, and Crassini (1998) established important differences between Australian and Chinese university students in their approaches to study. Specifically, using factor analysis they identified a different factor structure for Australian university students than for university students from the Chinese cultures of Hong Kong, Singapore, and Malaysia. Four factors were identified for each group. The factors for the Australian students were associated with a Meaning Orientation, a Nonacademic Orientation, an Anxious-Rigid Orientation, and a Goal Orientation. The four factors identified for Chinese students were an Anxious-Surface Orientation, a Self-motivated-Reflective Orientation, an Efficiency Orientation, and a Comprehension Orientation.

In later work Smith and Smith (1999) provided a more fine-grained scale-by-scale analysis of the ASI results and identified several differences between the two groups. Smith and Smith were able to draw several conclusions from these studies that had significance for the design and delivery of distance education programs to Chinese learners. Like Kember (1999), Smith and Smith suggested that distance education materials and delivery systems demanding deep processing could be effectively used and that Chinese students did not conform to the stereotype of being either surface or rote learners (Biggs, 1990; Kember, 1998, 1999). Similar observations have also been made by Biggs (1990, 1991, 1992) and Kember (1998). Smith and Smith also drew attention to a need to provide some further forms of student support, such as sample assessment material, to assist in overcoming the stronger fear of failure that was identified among the Chinese students. In addition, the results of that study indicated a need for support to assist Chinese students in the effective organization of their study and in the development of conceptual frameworks in the subject matter they were studying. The Smith and Smith (1999) investigation also confirmed earlier findings by Baron (1998) and Andrews, Dekkers, and Solas (1998) that these students had a strong need for structure and instructor guidance. They suggested that the use of a clear structure is important, but that there is need to encourage students to move beyond the structure and to use their skills to become confident in developing and expressing their own ideas and their own conclusions based on their better (than the Australian sample) use of evidence.

In their comparative study of Open University of Hong Kong students and those from the Open University of Sri Lanka, Calder and Wijeratne (1999) identified two factors common to the two groups. The first represented a deep/strategic approach associated with items involving looking for meaning, using evidence and logic, interrelating ideas, organization and management of study, and understanding. A second factor represented a surface approach comprising scales associated with memorization, “difficulty in seeing any overall picture and worries about getting behind in their studies” (p. 122). These findings form an interesting comparison with the factor structure identified by Smith et al. (1998) in their sample of Chinese students, which contained a subset of Hong Kong students. First, Smith et al. identified four factors similar to the two factors identified by Calder and Wijeratne and, second, the same observation was made in both studies that the ASI is a robust instrument for use across different cultural groups. It needs to be noted here, however, that Calder and Wijeratne used the shortened version of the ASI (ASSI), whereas Smith et al. used the longer 64-item ASI.

Unfortunately, a comprehensive comparison of the factors identified in the two studies cannot be made. Although the Smith et al. (1998) article contains the complete details of the factor loadings for each ASI scale, the Calder and Wijeratne study does not. It appears, though, from the prose description provided in the latter study that the surface factor identified by Calder and Wijeratne is similar to the Anxious-Surface factor identified by Smith et al. The Deep/Strategic factor in the Calder and Wijeratne study is similar to the Self-Motivated Reflective factor identified by Smith et al. It also appears that components of the Deep/Strategic factor can be found split between the Efficiency and Comprehension factors identified in the Smith et al. study.

Situated in these comparisons of factor structures is Rea’s (1996) notion of the “reformulation approach” (p. 17) and the “challenge approach” (p. 20). The reformulation approach, according to Rea, is characterized by learners who work largely only within the syllabus and materials provided and see the learning task as the reformulation in their own words of the content presented. Rea makes the point that a reformulation approach can still engage a deep approach where the student’s interest is in making strong and meaningful connections between various parts of the course. The student is, in Rea’s view, engaging with learning for meaning, although this is being achieved through reformulation of material that has been provided. She distinguishes between this approach and a second reformulation approach where the object is not to seek meaning, but to encode for recall and regurgitation in assessment.

A challenge orientation is characterized by the student who views the learning materials as challenging their own interpretations and understandings and who constructs meaning through this restructuring of material into new and existing schema. These are interesting distinctions to make in the context of Asian learners and help to provide further insight into the complexities of the stereotype of rote learning among Asian students that has been discussed and challenged by a range of authors (Biggs, 1990, 1991, 1992; Kember, 1998, 1999). The reformulation approach where meaning and understanding is sought may not be readily distinguished from the reformulation for recall approach. Also attractive from a cross-cultural research perspective is the central place Rea gives culture and context in understanding students’ learning, where she suggests that the culture and social context in which a student learns are clearly related to the understandings derived.

Both Smith et al. (1998) and Smith and Smith (1999) lamented the fact that a number of studies designed to identify the learning approaches, styles, and strategies of different cultural groups did not sufficiently define or control for the culture under investigation. Both articles point to numerous studies designed to provide research information on the learning approaches of groups of students from different nations and to test how these approaches are different among groups. A number of studies, however, have regarded Asian students as a homogeneous group and have not attempted to distinguish between the different ethnic groups. Work by Gassin (1982), Noesjirwan (1970), Samuelowicz (1987), and Barker, Child, Gallois, Jones, and Callan (1991) represents research where no attempt was made to distinguish between these groups. Other work, however, has controlled for ethnicity by drawing the student participants from one country. Most of these studies were conducted using Chinese students, with Biggs (1990, 1991, 1992), Kember and Gow (1990), Volet and Kee (1993), and Sadler-Smith and Tsang (1998) all using Hong Kong students. The studies by Smith et al. (1998) and Smith and Smith (1999) drew the Chinese students in their samples from a number of Asian countries.

Rizvi and Walsh (1998) have warned against the development of fixed conceptualizations of cultural characteristics such that variations in the culture, and between individuals in that culture, may become hidden or not considered at all. It is arguable that both the Smith et al. (1998) and the Smith and Smith (1999) articles were deficient in not differentiating the sample of Chinese students sufficiently. Although both those research projects defined the Chinese sample in terms of a Chinese dialect being the students’ first language, that they were recent arrivals in Australia and studying in their first semester at an Australian institution, neither study controlled for nation of origin. The Chinese sample of students included students from Hong Kong, Singapore, or Malaysia. Smith (2000) has further analyzed the data from the Chinese sample by calculating factor scores for each of the three national groups on each factor. In that study she showed that there were no significant differences among the three groups in their factor scores on the Anxious-Surface, the Self-Motivated/ Reflected, or the Comprehension factor. However, she does report that Hong Kong and Singapore students scored significantly higher than the Malaysian-Chinese on the Efficiency factor. Supportive of the Rizvi and Walsh (1998) warning of fixed conceptualization, Smith also identified a significant country by gender interaction for the Anxious-Surface factor, where Hong Kong and Singapore female students scored higher than their male compatriots; and Malaysian-Chinese male students scored higher than the Malaysian-Chinese female students. Smith (2000) offers an explanation for these findings in terms of differences among the groups in their language and sociocultural experiences.

The current investigation focused on the implications of differences between the three groups for the design and delivery of distance education and open learning programs in an analysis similar to our (Smith & Smith, 1999) comparative study of Australian and Chinese students. Consistent with this, the current investigation concentrates on an analysis of difference at the ASI scale level, but disaggregates the data to identify the three different Chinese national groups.

Participants were 192 on-campus Chinese students from Malaysia, Singapore, or Hong Kong drawn from two universities in Australia. This sample forms part of a larger sample of 248 overseas Chinese students in the Smith et al. (1998) study. These students were selected on the basis that a Chinese dialect was their first language and that they were recent arrivals in Australia, being in their first semester of study. Of the 192 Chinese students, 89 were from Malaysia (43 male and 46 female), 65 from Hong Kong (41 male and 24 female), and 38 from Singapore (12 male and 26 female). The criterion that students be in their first semester of study in Australia was important to minimize the possible changes in learning approaches that might occur as a function of exposure to Australian culture and educational methods. All the students were in business or computing undergraduate programs.

The Approaches to Studying Inventory was administered to the students during scheduled classes after their written consent to participate had been obtained. Students were instructed to answer the questionnaire in terms of their general approach to study and not in terms of the specific program in which they were enrolled.

The ASI consists of 64 items measuring 16 scales, which are Deep Approach, Interrelating Ideas, Use of Evidence, Intrinsic Motivation, Surface Approach, Syllabus-Boundness, Fear of Failure, Extrinsic Motivation, Strategic Approach, Disorganized Study, Negative Attitudes, Achievement Motivation, Comprehension Learning, Globetrotting, Operation Learning, and Improvidence.

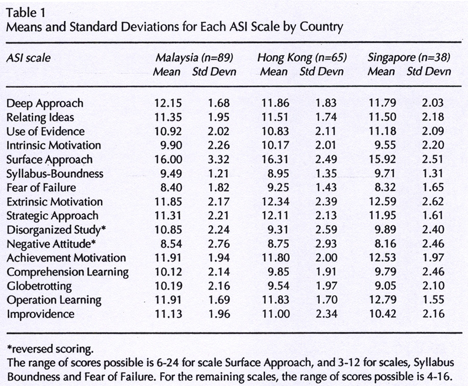

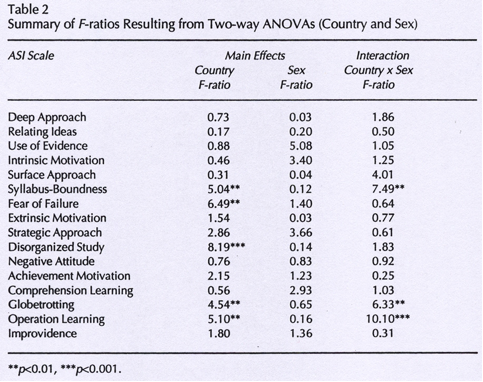

Means and standard deviations for each of the three subgroups on each ASI scale appear in Table 1.

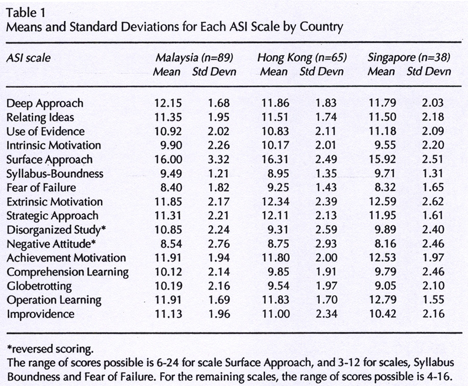

Two-way analyses of variance were computed for each scale of the ASI, with country and sex being the two independent variables. The results of these ANOVAs are shown as Table 2. Following Harper and Kember (1986), Richardson, Morgan, and Woodley (1999), and Smith and Smith (1999), to avoid a Type 1 error that is likely to occur where multiple statistical tests have been carried out on the same sample, an alpha level of 0.01 was used to establish significance rather than the more conventional 0.05 level.

Significant differences by country were shown for the ASI scales Syllabus-Boundness, Fear of Failure, Disorganized Study, Globetrotting, and Operation Learning.

Scheffé (1959) tests were applied to each of these scales to determine which pairs of countries yielded the significant results. Results of these tests provided the following more detailed information.

Syllabus-Boundness. Malaysian-Chinese and Singapore students were significantly more syllabus-bound than Hong Kong students. There was no significant difference between Malaysian-Chinese and Singapore students.

Fear of Failure. Hong Kong students had a significantly higher fear of failure than Malaysian-Chinese or Singapore students, between whom there was no significant difference.

Disorganized Study. Malaysian-Chinese students exhibited significantly more disorganized study than Hong Kong students, whereas there was no significant difference between Singapore students and the other two groups.

Globetrotting. Malaysian-Chinese students scored significantly higher than Singapore students on the Globetrotting scale (studying without aiming for a strong grasp of the subject matter). There was no significant difference between the Hong Kong students and the other two groups.

Operation Learning. Singapore students scored significantly higher than Malaysian-Chinese and Hong Kong students on this scale, whereas there was no difference between the Malaysian-Chinese and Hong Kong students.

Statistically significant interactions (see Table 2) between country and sex were obtained for the ASI scales, Syllabus-Boundness, Globetrotting, and Operation Learning. For both Singaporean and Hong Kong students, women were more bound to the syllabus than were men; however, in the case of Malaysian-Chinese students, women were less syllabus-bound than males. For both Singaporean and Hong Kong students, women were more inclined to globetrot than men, but this is reversed for Malaysian-Chinese students where women were less inclined to globetrot than their male counterparts. Both Singaporean and Hong Kong female students scored higher than their male counterparts on Operation Learning, but for Malaysian-Chinese students female students scored lower than men.

In summarizing these interactions, it is clear that for both the Singaporean and Hong Kong samples the pattern of difference between the sexes is the same, but for Malaysian-Chinese students this pattern is reversed.

Although all students were of a common Confucian cultural heritage background, differences in learning behavior were found among the three national groups of Chinese students. Both the Malaysian-Chinese and the Singaporeans appear to be more dependent than those from Hong Kong as measured by syllabus-boundness. The Malaysian-Chinese and Singapore groups showed strong preferences for clear, highly organized, and well-structured learning programs and are inclined to confine their learning to the prescribed readings and to teachers’ instructions and directions. This finding for the Malaysian-Chinese students may be interpreted through Hofstede’s (1986) concept of Power Distance. Hofstede showed Malaysians to be high on power distance in comparison with Hong Kong people. Accordingly, these students may consider teachers to be people in a position of power and authority whose instructions must be followed. For Singaporean students, an interpretation of the result may lie in a combination of Volet and Kee’s (1993) and Yuen and Lee’s (1994) findings that Singaporean students place considerable importance on the development of conceptual understanding. Biggs (1994) has commented that a condition for constructivist learning is “a well-structured knowledge base, that provides depth (for conceptual development); and breadth (for conceptual enrichment)” (p. 321). Possibly the syllabus-boundness exhibited by Singapore students is a mechanism to define clearly for themselves the breadth and depth of knowledge expected such that they construct their learning within those parameters. This interpretation of the results for Singaporean students may provide further evidence for Rea’s (1996) notion of a reformulation approach among students as they work with learning materials. Rea makes the point that a reformulation approach can still engage a deep approach because the student’s intent is in meaningful connections between different parts of the course.

In a distance education context these findings are of some significance and provide further evidence of the need for structure and instructor guidance noted by Baron (1998) in her work with Singaporean students. Although Andrews et al. (1998) have reported the same observation, it is noteworthy that their more heterogeneous sample of Asian students did not include students from Hong Kong. Smith and Smith (1999) suggested that Chinese students have a strong need for “structured programs of instruction where the logic of that structure is transparent to the student” (p. 77). The current results indicate that this observation is less true of the Hong Kong students than it is of the other two groups. For distance educators providing instructional programs to Hong Kong students, it would appear that there is greater scope for enabling students to develop their own structures in learning and to develop these structuring skills in a more sophisticated way. It is worth recalling Vermunt’s (1996) finding that students tend not to develop a learning strategy if it is provided by the instructor. Considerable evidence in the literature (Vermunt; Sternberg & Grigorenko, 1997) indicates that the learning strategies of students can be developed through experience and coaching such that students can be taught how to engage in and restructure learning materials and sequences so as to provide greater meaning. Kember (1999) makes the point that the design of distance learning materials can through their structure at least partly determine the approach to learning that students adopt. In Rea’s (1996) terms again, her suggestion of a challenge orientation among students is characterized by restructuring to challenge existing interpretations and understandings. From this point of view, there is value in providing a structure to instructional materials that leaves sufficient scope for students to restructure them as part of their strategy for developing meaning and to link these newly developed structures to their own interpretations and understandings, or to challenge those understandings. An interesting example of this can be seen in Deakin University’s off-campus unit ECX701 Theory and Practice in Open and Distance Education, where students are continually challenged throughout the unit to reflect critically on their own experience and beliefs in the light of the material presented. The unit challenges students through a series of 42 small tasks that the student completes for assessment and that continually develop and further challenge the student to test new understandings against prior understandings. This unit is designed to teach students to adopt, in Rea’s (1996) terms, a challenge approach rather than one of reformulation. This may be a more successful teaching approach with Hong Kong students than with the other two groups.

Although both Singaporean and Malaysian-Chinese students were shown to be high on the syllabus-bound scale, a significant country-by-sex interaction indicates that this is more typical of Singaporean female students than of male students. Interestingly, this situation is reversed for Malaysian-Chinese students. Any convincing explanation for this rather intriguing result must come through further research to verify its reliability or otherwise. It is possible insofar as that approaches to study are influenced by educational and social experiences, the two sexes have different experiences in the two countries, but the current investigation has provided no data to assess the value of this suggestion.

In comparison with Singaporean and Hong Kong students, Malaysian-Chinese students have been shown in the present study to be more disorganized in their approach to learning. These results indicate that they are relatively poor managers of their study time and experience greater difficulty in initiating and maintaining their study behaviors. Malaysian-Chinese students also scored higher than the Singaporeans on the Globetrotting scale, indicating a stronger tendency to study without aiming for a strong grasp of the subject matter. A tendency to distinguish only poorly relevant from irrelevant material is another feature of globetrotters. Generally, it would seem that in this study the Malaysian-Chinese students are not as effective and efficient in their approach to learning as the other two groups. Given that English has not been a language of instruction for the Malaysian-Chinese students, and that these students were in their first semester in an Australian university, it is possible that the inefficient learning strategies adopted by these students may be attributed to English-language skills.

In addition, however, there is a possibility suggested by the higher degree of syllabus-boundness exhibited by the Malaysian-Chinese students that conceptualization and understanding may not be such high priorities. If this is indeed the case, globetrotting may be at least partly the result of lack of conceptual clarity of the subject matter. It is useful again to invoke Rea’s (1996) notion of the reformulation approach. Although there is evidence that the Singaporean students may be using a deep approach in the reformulation paradigm, it seems likely that the Malaysian-Chinese students are using the reformulation approach more superficially, which may be associated with less advanced skills in English. Biggs (1990) has commented that an apparently surface approach is consistent with language unfamiliarity. For distance educators this result has some important possible consequences. First, it has been pointed out by Reeve, Gallacher, and Mayes (1998) that the very openness of open education may be a barrier to some students. There seems to be a need, therefore, with the Malaysian-Chinese students, to ensure the development in students of a set of skills that enable them to identify and focus clearly on the learning or assessment outcomes they wish to achieve. There is also, arguably, a need to provide strategies that enable them to achieve these outcomes in a context of possibly less familiarity with English. This is likely to mean structuring learning materials in a quite definite way and linking the content of those materials to learning strategies and language that can be effectively used. Second, there is a need to develop these strategies gradually so that students can begin to move beyond a surface approach to the learning materials and start engaging a deeper reformulation approach as advocated by Peters (1998) in his discussion of the development of autonomous learning among Asian students.

The support that distance educators and institutions provide for their distance students is worthy of some examination in the light of the finding that Malaysian-Chinese students exhibited more disorganized study habits than the Hong Kong students. Smith and Smith (1999) pointed to the possibility that disorganized study might be associated with a higher need for structure and instructor guidance and that students would benefit from assistance in developing effective study techniques and time management. Clearly the results of the current study show that Malaysian-Chinese students among the three groups investigated here have the greatest need of this form of assistance, such that distance educators operating in this environment may need to spend more time with students in establishing these habits. Given the possible association of this finding with the syllabus-boundness finding, there would appear to be reason to provide specialized assistance to students to help them develop structure both in terms of their approach to conceptualizing content of study and in developing their study habits.

Singaporean students were shown to be high on operation learning when compared with both the Malaysian-Chinese and the Hong Kong Chinese students, with the latter two subgroups not differing significantly from each other. It may be suggested, therefore, that Singaporean students are more systematic, logical, and objective in their approach to learning and problem-solving and tend more to rely closely on facts and details when forming concepts or reaching conclusions. This cognitive approach to learning seems to correspond closely with the kinds of skills that are highly valued by both Singaporean teachers and students (Volet & Renshaw, 1995; Volet & Kee, 1993). The skills involve clear and logical thinking together with the ability to present arguments in a well-integrated fashion. This finding may, however, indicate a need for distance educators to consider providing instructional sequences and exercises to Singaporean students to promote development of insightful thinking and greater use of inductive logic. At the same time, Smith and Smith’s (1999) results indicate that Chinese students are generally higher on operation learning than are Australian students. Accordingly, there would not appear to be any particular need to provide extra assistance to the Malaysian-Chinese and Hong Kong students on logical thinking merely because they did not score as highly on this scale as the Singaporean students.

Hong Kong students scored significantly higher than Malaysian-Chinese and Singapore students on the Fear of Failure scale, indicating that they are more anxious in their learning and more concerned about the possibility of failing. A number of previous studies have attributed to Hong Kong students the features of high competitiveness, strong personal drive to achieve academic excellence, and strong parental pressure to achieve (Biggs, 1990; Balla, Stokes, & Stafford, 1991; Sadler-Smith & Tsang, 1998). In addition, Cheung, Conger, Hau, Lew, and Lau (1992) have shown that Hong Kong people are more anxious than Chinese from other nations. These findings from other research provide a background of support to the finding of higher levels of anxiety and fear of failure among the sample of students in this study. Smith and Smith (1999) suggested that the development and provision of model pieces of assessment for students with a high fear of failure would be useful, and this would appear to be more useful to the Hong Kong students than to the other two groups. In addition, providing greater support to encourage confidence in students preparing for examination and assessment would be well placed, together with opportunities to discuss assessment requirements with instructors.

The study behaviors of Chinese students from the three different nations indicate some important differences. Malaysian-Chinese students are shown to have less developed study skills and appear to be less efficient in their approach to learning than either the Hong Kong or the Singaporean students. Hong Kong students, on the other hand, appear to have developed their study skills further, such that they exhibit considerable efficiency in their approach to learning and appear to be more prepared to move beyond the instructor-provided syllabus. The high level of anxiety that Hong Kong students experience in their studies seems to have a positive, rather than negative, effect in driving students to adopt more appropriate and efficient study strategies. In comparison, Singaporean students are shown to be the most efficient group of learners, with study strategies that are systematic, organized, objective, and purposeful.

In summary, it appears that the differences among the three groups can be conceptualized with some clarity and perhaps placed in the context of Rea’s (1996) suggestions of the reformulation and the challenge approaches. Singaporean students appear to confine their approach to study to the materials and syllabus provided, but to use a deep approach and a strong focus on study outcomes in the reformulation paradigm. Malaysian-Chinese students would appear, like the Singaporean students, to confine their approach to what is provided in instruction, but to adopt a more surface and less organized form of the reformulation approach. The Hong Kong students seem to be more willing to move outside the structure provided, perhaps toward adopting something more like Rea’s challenge approach, but to be more influenced by anxiety and a fear of failing. In this theoretical framework it is also possible to suggest a relationship between these results and the Surface and Deep/Strategic factors identified by Calder and Wijeratne (1999) and the more complex factor structure identified for Chinese learners by Smith et al. (1998).

The present study indicates that differences in study strategies can occur among the individual national groups that comprise what may otherwise appear to be a fairly homogeneous group of students. As noted above, few comparative studies on learning have been carried out among Chinese students from different nations. Further research needs to be conducted with these more finely cut samples of Chinese students if the present findings are to be useful in distance education decision-making for these clienteles. The present study has shown that differences among the three national groups of Chinese learners can be identified, so considerable care needs to be taken to ensure results from one group are not necessarily generalized to others. Rizvi and Walsh’s (1998) warning against the development of fixed conceptualizations of cultural characteristics takes on a special significance as a result of the current study.

Andrews, T., Dekkers, J., & Solas, J. (1998, December). What really counts? A report on a pilot investigation identifying the significance of learning style and cultural background for overseas students in flexible learning environments. Paper presented to the 3rd international conference on open learning, Queensland Open Learning Network, Brisbane.

Balla, J.R., Stokes, M.J., & Stafford, K.J. (1991). Using the studying process questionnaire to its full potential. Unpublished technical report, City Polytechnic of Hong Kong.

Barker, M., Child, C., Gallois, C., Jones, E., & Callan, V.J. (1991). Difficulties of overseas students in social and academic situations. Australian Journal of Psychology, 43, 79-84.

Baron, J. (1998, December). Teaching online across cultures. Paper presented to the 3rd international conference on open learning, Queensland Open Learning Network, Brisbane.

Biggs, J.B. (1990, July). Asian students’ approaches to learning: Implications for teaching overseas students. Paper presented to the 8th Australasian tertiary skills and language conference, Queensland University of Technology.

Biggs, J.B. (1991). Approaches to learning in secondary and tertiary students in Hong Kong: Some comparative studies. Education Research Journal, 6, 27-39.

Biggs, J.B. (1992, January). Approaches to learning of Asian students: A multiple paradox. Paper presented at the symposium on student learning in a cross-cultural context, 4th Asian regional conference, Nepal.

Biggs, J.B. (1994). Approaches to learning: Nature and measurement of. International Encyclopedia of Education (vol. 1, 2nd ed., pp. 319-322). Oxford, UK: Pergamon Press.

Calder, J., & Wijeratne, R. (1999). The approaches to study of distance learners in two cultures: A comparative study. In R. Carr, O.J. Jegede, Wong Tat-meng, & Yuen Kin-sun (Eds.), The Asian distance learner (pp. 116-129). Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press.

Cheung, P.C., Conger, A.J., Hau, K.T., Lew, W.J.F., & Lau, S. (1992). Development of the Multi-Trait Personality inventory: Comparison among four Chinese populations. Journal of Personality Assessment, 59, 528-551.

Deakin University. (1998). ECX701 theory and practice in open and distance education: Study guide. Geelong: Deakin University.

Entwistle, N., & Ramsden, P. (1983). Understanding student learning. New York: Nichols.

Gassin, J. (1982). The learning difficulties of the foreign student and what we can do about them. Higher Education Research and Development Society of Australia, 4, 13-16.

Harper, G., & Kember, D. (1986). Interpretation of factor analyses from the Approaches to Studying inventory. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 59, 66-74.

Hofstede, G. (1986). Cultural differences in teaching and learning. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 10, 301-320.

Kember, D. (1998). Action research: Towards an alternative framework for educational development. Deistanc Education, 19(1), 43-63.

Kember, D. (1999). The learning experiences of Asian students: A challenge to widely held beliefs. In R. Carr, O.J. Jegede, Wong Tat-meng, & Yuen Kin-sun (Eds.), The Asian distance learner (pp. 82-99). Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press.

Kember, D., & Gow, L. (1990). Cultural specificity of approaches to study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 60, 356-363.

Noesjirwan, J. (1970). Attitudes to learning of the Asian student studying in the West. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1, 393-397.

Peters, O. (1998, November). Will the Asian distance learner become an autonomous learner? Paper presented to the 12th annual conference, Asian Association of Open Universities, Hong Kong, Open University of Hong Kong.

Rea, M. (1996). Adult learning: Constructing knowledge through texts and experience. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University.

Reeve, F., Gallacher, J., & Mayes, T. (1998). Can new technology remove barriers to work-based learning? Open Learning, 13, 18-26.

Richardson, J.T.E., Morgan, A., & Woodley, A. (1999). Approaches to study in distance education. Higher Education, 37, 23-55.

Rizvi, F., & Walsh, L. (1998). Difference, globalisation and the internationalisation of curriculum. Australian Universities Review, 2, 7-11.

Sadler-Smith, E., & Tsang, F. (1998). A comparative study of approaches to studying in Hong Kong and the United Kingdom. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 68, 81-93.

Samuelowicz, K. (1987). Learning problems of overseas students: Two sides of a story. Higher Education Research and Development, 6, 121-132.

Scheffé, H. (1959). The analysis of variance. New York: Wiley.

Smith, P.J., & Smith, S.N. (1999). Differences between Chinese and Australian students: Some implications for distance educators. Distance Education, 20, 64-80.

Smith, S.N. (2000, July). Differences in approaches to study between three Chinese national groups. Paper presented to the XVth congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, Warsaw.

Smith, S.N., Miller, R., & Crassini, B. (1998). Approaches to studying of Australian and overseas Chinese students. Higher Education Research and Development, 17, 261-276.

Sternberg, R.J., & Grigorenko, E.L. (1997). Are cognitive styles still in style? American Psychologist, 52, 700-712.

Vermunt, J.D. (1996). Metacognitive and affective aspects of learning styles and strategies: A phenomenographic analysis. Higher Education, 31, 25-50.

Volet, S.E., & Kee, J.P.P. (1993). Studying in Singapore—Studying in Australia: A student perspective. Occasional Paper No. 1. Perth, Western Australia: Murdoch University Teaching Excellence Committee.

Volet, S.E., & Renshaw, P.D. (1995). Cross-cultural differences in university students’ goals and perceptions of study setting for achieving their own goals. Higher Education, 30, 407-433.

Yuen, Chi-Ching, & Lee, S.N. (1994). Learning styles and their implications for cross-cultural management in Singapore. Journal of Social Psychology, 134, 593-600.

Swee Noi Smith is a member of staff in the School of Psychology at Deakin University in Australia. Her research interest is the learning approaches of students from different cultural groups, with a focus on the Confucian heritage cultures. She is a consistent contributor to the literature on cross-cultural learning. Her e-mail address is ssmith@deakin.edu.au.

Peter J. Smith is a member of the Faculty of Education at Deakin University. A psychologist by training, he has been a contributor to distance education theory and practice since the 1970s. He has a strong interest in the provision of distance education across different cultural groups. His e-mail address is pjbs@deakin.edu.au.