VOL. 16, No. 2, 37-57

This article explores the syntactic structure, cognitive functions, pedagogical features, and communicative characteristics of questions asked by participants in an asynchronous learning environment. Participants used fewer syntactic forms than observed in face-to-face postsecondary classrooms, but based on the Model of Productive Thinking (Barnes, 1983; Gallagher & Aschner, 1963), they exhibited higher levels of cognition. Questions at higher cognitive levels were found to stimulate more interaction than did those at lower levels. Compared with face-to-face interaction, students asked more rhetorical questions, using them to persuade, think aloud, and indirectly challenge other participants.

Cet article explore la structure syntaxique, les fonctions cognitives, les particularités pédagogiques et les caractéristiques communicatives des questions posées par les participants dans un environnement d’apprentissage asynchrone. Les participants ont utilisé moins de formes syntaxiques qu’observé dans des classes de cours de niveau post-secondaire, mais, basé sur le modèle de pensée productive (Barnes, 1983; Gallagher et Aschner, 1963), ils ont montré des degrés plus élevés de cognition. Les questions aux degrés cognitifs plus élevés se sont avérées stimuler plus d’interaction que celles aux degrés moindres. Comparativement à l’interaction en face à face, les étudiants ont posé plus de questions rhétoriques, les utilisant pour persuader, penser tout haut et, indirectement, mettre au défi les autres participants.

Teachers and students have well-developed schemata for asking and answering questions in a formal learning context. Because the rules governing classroom interaction have remained relatively unchanged since elementary school, they have essentially become part of the tacit knowledge shared by participants. But when the learning context changes from the familiar face-to-face environment to the asynchronous, textual context of the computer-mediated environment, long-established communicative norms and strategies also change. Just as rules such as those regarding turn-taking are no longer valid, the guidelines governing the process of asking and answering questions no longer necessarily resemble those we have internalized over the years.

What is a question? Hunkins (1995) defined questions as “complex linguistic structures designed to engage individuals cognitively and affectively in processing particular contents” (p. 114). At its simplest, a question is an expressed request for information. These requests can take a variety of forms and can fall into a number of different categories depending on the context in which they are being studied. This context also influences the terms chosen to describe questions as well as their definitions. Linguists have long concerned themselves with the grammar of questions (formal linguistics), the relationship between questions and answers (conversational analysis), and the function of questions (sociolinguistics). In the realm of teaching and learning, questions have been cited as not only the most often used, but also the single most important strategy employed by instructors (Ellis, 1993; Foster, 1983; Schiever, 1991).

Teachers’ questions and students’ responses are the main interaction in the traditional classroom, and as such they are essential to teaching and learning (Dillon, 1988). This interaction has been the subject of extensive research, but most of these studies have been conducted in the school system rather than in postsecondary institutions (Edwards & Bowman, 1996; Ellner & Barnes, 1983; Graesser & Person, 1994; West & Pearson, 1994). Even fewer have focused on the questions asked in the text-based, technology-mediated context of online teaching and learning (Muilenburg & Berge, 2000; Waugh, 1996).

The purpose of this study was first to identify both the linguistic structure of instructor/student questions (syntactic form) and the cognitive operations inherent in instructor/student questions (function). This information was then analyzed to determine if a relationship exists between question form and function and instructor and learner questions (along the dimensions of both form and function).

In addition to identifying linguistic structure and cognitive functions, this study also attempted to identify the pedagogical and communicative characteristics of questions asked in this online environment.

Research on questions and questioning in the context of education, whether K-12, postsecondary, or online, has addressed the frequency, associated wait time, and cognitive level of questions. Most of this research has addressed the issue of frequency: how often or how many questions the instructor asked either during a specific time or during a specific type of activity. Levin and Long’s (1981) report that teachers ask between 300 and 400 questions per day is in keeping with other research conducted in the school system. It is not, however, representative of the use of questioning in the context of postsecondary education. Here, few questions are asked. Less than 4% of instructors’ time was spent asking questions (Barnes, 1983; Graesser & Person, 1994; Smith, 1983; West & Pearson, 1994). Another distinction between the two contexts was Barnes’ finding that one third of the questions asked by college instructors remained unanswered. Although instructors ask most of the questions in face-to-face classrooms, this is not so for online learning environments. Blanchette (2000) found that 11% of instructor utterances were questions and that students contributed 69% of the questions. In the online context, the focus has tended to be on the frequency of student questions (Waugh, 1996).

Wait time (Rowe, 1972) is the period of silence that follows teacher questions (wait time I) and students’ responses (wait time II). This period typically lasts 1.5 seconds, but when extended to at least 3 seconds, increases in the length and correctness of student responses, number of students volunteering responses, number of student-initiated questions, and achievement-test scores have also been observed (Rowe, 1987). Rowe’s conclusions are supported by Tobin (1987), who conducted a review of 50 published studies of wait time. Wait time, or think time, is inherent in asynchronous interaction; one of the benefits of online learning is how it allows participants the opportunity to provide a thoughtful response to questions (Blanchette, 1999; Eastmond, 1995).

The cognitive level of instructor questions in the school system has been studied extensively (Dillon, 1988, 1994; Gallagher & Aschner, 1963; Guilford, 1956; Hunkins, 1995; Morgan, 1991; Wilen, 1991). Although questioning plays an important role in classroom interaction, some people maintain that teachers’ questions, especially those at the lower cognitive levels, have a negative outcome. Dillon (1994) takes the position that such questions neither stimulate student thinking nor encourage participation. At the postsecondary level, studies have found that questions asked by instructors tend to be at the lower cognitive levels (Barnes, 1983; Fischer & Grant, 1983). Barnes found that 80% of questions in college classrooms asked students to recall facts.

The Structure of Intellect model was first proposed by Guilford in 1956. This model has three separate but interconnected dimensions: (a) the content of the information; (b) the operation performed on the information; and (c) the products resulting from that processing. The second dimension—operations—is further subdivided into five categories: cognition, memory, divergent production, convergent production, and evaluation. It was also the part of the model of most relevance to education, and based on this element, Gallagher and Aschner (1963) developed a classification system that incorporated the concept of productive thinking to describe the cognitive levels observed in classroom interaction. The cogni- tive categories in their model are (a) routine thinking, (b) cognitivememory, (c) convergent thinking, (d) divergent thinking, and (e) evaluative thinking. In 1983 Barnes applied the Gallagher and Aschner system to the college setting in her landmark study of instructors’ questioning behaviors in 40 classes at a variety of postsecondary institutions. She found that most instructors asked questions that required little or no thought on the part of students. Edwards and Bowman (1996) also used Gallagher and Aschner’s model in their study of instructors’ questioning in a nontraditional postsecondary classroom, which revealed that the type of questions asked were influenced by instructional format (lecture, media presentation, or student presentation). To date this model has not been applied to an online learning environment.

The 17 participants in this study are following a graduate degree program that uses computer conferencing to facilitate interaction. The transcripts of their online interactions, conducted over a period of eight weeks, consist of 556 messages distributed among 27 subconferences. From these messages, 352 were selected for analysis. The messages were posted in seven topic conferences, which were further divided into 22 small-group discussion conferences that were conducted entirely online. Discussions that comprised a combination of online and video, audio, or face-to-face interaction were excluded from the analysis.

This study takes a discourse analysis approach to the study of online interactions by viewing them as conversations—linguistic units larger than a sentence or utterance and involving more than one person—that take place in a specific context (Schiffrin, 1994). At the same time, following Green and Harker (1988), the transcripts were analyzed from a variety of perspectives—linguistic, cognitive, and pedagogical—in order to enhance the depth of the overall study. Using the HyperResearch qualitative software package, questions were categorized according to the linguistic, pedagogical, and cognitive classifications listed below.

Four major syntactic categories—statements, questions, commands, and exclamations—are sufficient to describe simple sentences. These are commonly referred to as declarative, interrogative, imperative, and exclamatory sentences. Interrogative sentences, or questions, can further be divided into two subcategories—Yes-no questions and Wh- questions— depending on the type of answer they would be expected to receive (Quirk & Greenbaum, 1973). Although some linguists maintain that these two subcategories are sufficient to classify all questions, others subdivide the list to include a number of minor question types. This study focuses on the major categories of Yes-no questions and both the narrow and broad forms of Wh- questions. With the exception of alternative questions, which can belong to either the Yes-no or Wh- groups, the other minor categories are variants of Yes-no questions and are discussed in less depth. Following is a simple taxonomy of question types arranged according to syntactic form.

1. Yes-no questions. These polar interrogatives begin with a verb (be, have, or do) or a modal verb followed by the subject. Are we meeting after class?

2. Wh- questions. These generally begin with an interrogative word (who, what, when, where, why, how). They are commonly known as information questions because they ask the responder to provide particulars (Woodbury, 1984).

1. Alternative or disjunctive questions. These can take either the verb-subject form or the Wh- form. Disjunctive questions offer a choice of answer. Do you want to meet before class or after?

2. Tag questions. When a particle is added to the end of a declarative sentence, the entire statement becomes a question. This type of question generally seeks confirmation. We’re meeting after class, right?

3. Declarative or indirect questions. These are questions that appear on the surface to be statements, but the underlying form is that of a question. . assume we’re meeting after class is interpreted as Are we meeting after class?

4. Moodless questions. These nonclausal forms have neither a subject nor a finite verb. Questions?

5. Echoic questions. These consist of a repetition of a portion of a preceding utterance and usually are a request for clarification. (a) We’re meeting after class; (b) After class?

Aschner, Gallagher, Perry, and Afsar (1961) identified the following five categories of thought processes (examples are from the course transcripts).

1. Routine (R) questions. These refer to procedural matters, structure of class discussion, and approval or disapproval of ideas. Are there any questions?

2. Cognitive-Memory (C-M) questions. These require the use of recall or recognition in order to reproduce facts and other items of remembered content. What are the five steps in Knowles’ self-directed learning model?

3. Convergent Thinking (CT) questions. The tightly structured framework of these questions requires the analysis or integration of given or remembered data, leading to one expected result. Based on this model, what are the goals of education?

4. Divergent Thinking (DT) questions. These questions permit an independent generation of ideas, directions, or perspectives in a data-poor situation. Why is learning necessary?

5. Evaluative Thinking (ET) questions. These questions are concerned with values rather than facts and convey a judgmental quality. Is this approach worth the effort? (pp. iv-viii)

Verbal interaction is inherently complex, however, and this is no less true in the classroom. When deciding which of these categories best describes a particular question, such materials as readings or other resource materials can be determining factors, as can the content of lectures and earlier discussions. For example, the question What are the implications for adult education? could be a Cognitive-Memory question if a list of implications had been provided in the course reading package. It could be a Convergent Thinking question if it asked students to draw conclusions from a reading or earlier discussion (data-rich context), or it could be a Divergent Thinking question if this was an entirely new topic and the goal was to encourage participants to generate new ideas (data-poor context). The appropriate category can only be determined in context.

Unlike linguists, educators use a wide variety of terms to describe and categorize questions. Morgan (1991) selected 50 terms, 3 major categories, and 16 subcategories that have been used to describe questions used in the classroom. Hunkins (1995) identified an equally broad range of terminology as well as 8 classification systems. The following taxonomy of question types contains the terminology pertaining to the current study.

1. Educative questions. The most basic distinction is the one between everyday questions and educative questions (Dillon, 1982; Hunkins, 1995; Morgan, 1991).

2. Epistemic questions. These are either display questions or referential questions.

In general conversation, most questions are of the referential variety (Weber, 1993). This contrasts with classroom interaction where display questions are common (Gaies, 1983). In the classroom, most student-initiated questions are referential, although instructors frequently respond by asking a display question (Markee, 1995).

3. Transpersonal questions. These “ask students to reflect on their inner voices, their inner life and also on the infinite, the big picture � who they are and how they feel about themselves and their world” (Hunkins, 1995, p. 108).

4. Initiating questions. These questions are used to introduce a new discussion topic.

5. Probing questions. Probing questions can be used to remove ambiguity, to request elaboration, or to broaden participation.

An analysis of the course transcripts identified 297 questions. Of these, the instructor asked 68 (22.9%) and the students asked 229 (77.1%). These results are consistent with earlier studies indicating that students in online courses ask most of the questions. Mapping the responses to the questions showed that six (8.8%) of the instructor’s questions went unanswered. This is considerably lower than the 33% identified by Barnes (1983).

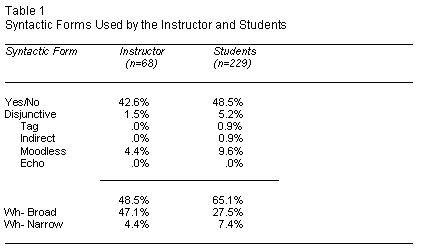

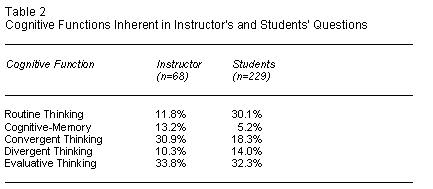

Syntactic form was examined according to the major categories of Yes-no, Wh- broad, and Wh- narrow questions. Both the instructor and the students used Yes-no questions most often and Wh- narrow questions least often (Table 1). Although the alternative or disjunctive form can be a variant of either Yes-no or Wh- questions, all instances of this minor form were found to belong to the Yes-no classification. Participants’ usage of these variant forms was limited, with the Moodless form being used most frequently.

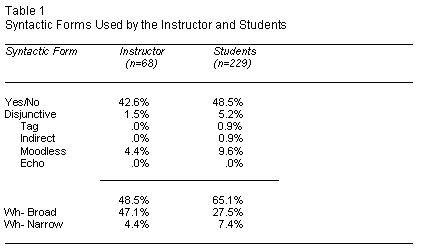

Although all five categories of cognitive function were evident in both the instructor’s and the students’ questions, the Evaluative Thinking function was the most frequently used by all participants (Table 2).

As can be seen in Table 2, 75% of the instructor’s questions were at the higher cognitive levels. Most students’ questions (64.6%) were also at the higher cognitive levels.

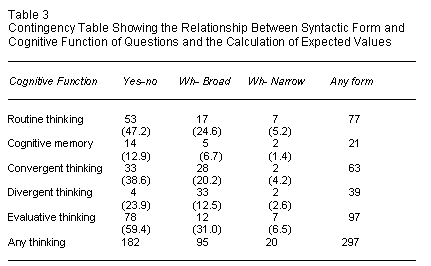

Incidences of syntactic form and cognitive function were cross-tabulated, and these values were compared with the expected or theoretical frequencies (Table 3). The value of �2 was found to be 77.57. For df=28, this is highly significant because the value of 48.28 is significant at the 1% level. This would indicate that there is a stronger relationship between the syntactic form and cognitive function of questions than would appear by chance.

In order to determine if there was a relationship between either the form or function of questions asked by the instructor and students, participants’ use was plotted across each of the seven discussions. There does not appear to be any relationship between the syntactic forms used by the instructor and the students. That is, an increase or decrease in the use of any particular form by the instructor does not correspond to any increase or decrease in the use of that form by students.

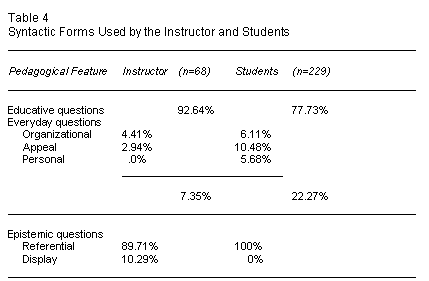

Questions exhibiting each of the four classes of pedagogical features— educative/everyday, epistemic (referential/display), transpersonal, and probing—were found in the transcripts. The occurrences of each class are itemized in Table 4.

The vast majority of both the instructor’s and students’ questions were of an educative nature. Everyday questions were asked at the level of Routine Thinking and were concerned with organizational issues such as requests for clarification (e.g., “Do you mean four each or four as a group?”), personal questions (e.g., “Have you moved?”), or appeals for feedback (e.g., “What do you think of that?”). The instructor asked only five everyday questions (3 organizational and 2 appeals) whereas students asked this type of question 51 times (14 organizational, 24 appeals, and 13 personal questions). The instructor’s questions were primarily referential, with only seven display questions being asked. Students asked referential questions exclusively. Students also asked seven transpersonal questions whereas the instructor asked only one. The instructor asked probing questions on 23 occasions whereas students asked this type of question three times.

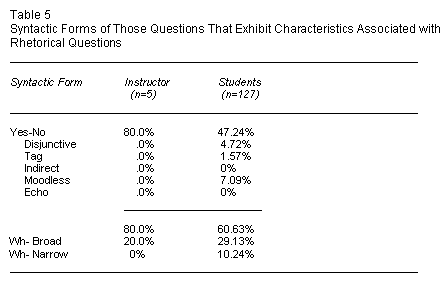

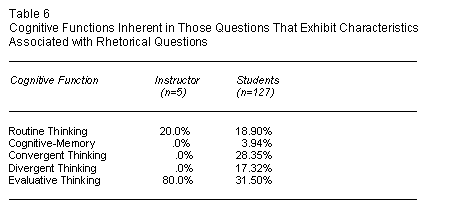

When I examined the transcripts in order to identify the foregoing characteristics of questions asked by participants, a number of other traits became evident. First, questions were frequently asked one after the other, or “chained” together. Second, numerous uses of the phrases . wonder and What if were observed. Third, it was not an uncommon practice for participants to answer their own questions. Finally, it was noted that these three characteristics often appeared in conjunction. In face-to-face interaction, these traits are frequently descriptive of rhetorical questions. The syntactic form of questions exhibiting these characteristics is shown in Table 5, and the cognitive function of these questions can be found in Table 6.

Another feature that was characteristic of student questions took the form of an Appeal (n=24). These questions invited a response and were usually found at the end of a message. The majority of the Appeals were at the level of Routine Thinking (92.9%) and in the Yes-no form (71.4%). Of these, the Moodless syntactic form was used more than half of the time (57.9%). The instructor used the Appeal question format twice.

Although it is possible to use basic statistical methods to describe some features of questions and questioning, other elements are more difficult to quantify. Nonetheless, an exploration of these elements is necessary to the study of the questions asked by participants in this asynchronous context if the role of questions is to be fully understood. In keeping with a multiple perspective analysis approach (Green & Harker, 1988), the following discussion also addresses those aspects that are not amenable to quantification.

For the most part, participants in this online environment used the same syntactic forms as would be found in a face-to-face classroom, albeit in a somewhat more limited range. For example, no Echo questions were identified online. It is possible that Echo questions are considered too ambiguous for online interaction. Simply repeating what was said without any paralinguistic cues provides no insight into what additional information is required.

The potential for ambiguity may also explain why indirect questions were rarely used. This syntactic form is relatively dependent on changes in intonation to distinguish it from a statement. In the transcripts, participants used . wonder and perhaps to help identify their indirect questions (e.g., “I wonder if such a profile already exists”).

Another common syntactic form that was almost nonexistent in this online classroom interaction is the Tag question. This is notable because Tag questions have long been considered a characteristic of feminine speech (Eakins & Eakins, 1978; Lakoff, 1975; Tannen, 1990). It is such a consistent marker that even when participants in an online discussion used aliases to conceal their identities, female sex was assigned to participants in large part according to their use of this syntactic form (Gal, 1995; Herring, 1996; Wallace, 1999). Because three quarters of the participants in the current study were female, if Tag questions were a consistent gender marker, a much larger number of such question should have been found. This could support the research that identifies power rather than gender as a more important determining factor in the use of “feminine” speech characteristics (O’Barr & Atkins, 1980; Wallace, 1999). Participants in this course were relatively homogeneous with relation to social and professional status.

With regard to the cognitive function of questions, 75% of the instructor’s questions were at the higher cognitive levels. This proportion of questions at the higher and lower cognitive levels is almost the opposite of the proportions in Barnes’ (1983) study of face-to-face interaction that found that 80% of instructors’ questions required little or no thought on the part of students. This would appear to indicate that interaction in this online context was more intellectually demanding than that found in the face-toface classroom. One possible explanation for this disparity relates to the organizational features of online interaction. The asynchronous environment can be structured so that routine questions of an organizational or administrative nature are posted in an entirely different area from where discussions of course content would take place. Second, the immediacy of face-to-face interaction may influence instructors to use routine questions as a form of comprehension check. It is also possible that face-to-face instructors may use these lower-level questions as a type of filler or placeholder, as a segue from one part of a lecture to another, or as a frame or scaffold to focus students’ attention on what is to come. The online instructor, being unable to observe paralinguistic cues, would gain little from adopting these strategies. In text-based interactions, bullets, numbering, and white space are among the more effective organizational tactics used to focus attention or make the transition from one point to the next.

Unlike face-to-face interaction where students ask few questions (West & Pearson, 1994), students in this online context asked many questions. Routine Thinking questions were common (30%). This reflects the phatic nature of student-student interaction. Students also asked for clarification and made appeals for feedback from other participants. These all took the form of Routine Thinking questions, and this closely parallels the type of question-asking that occurs in face-to-face conversations. When students asked Cognitive-Memory questions (5%), they were requests for specific factual information that they knew was available to another student. For example, one student asked, “Can you tell me how long that’s supposed to take? I know [name of previous instructor] discussed it, but it’s slipped my mind.” Convergent Thinking questions accounted for only 18% of these. Nearly 65% of student questions were at the higher cognitive levels.

When asked by a student, Convergent Thinking questions appeared to be seeking more details or some form of explanation (e.g., “What would be the benefits of grouping developmental levels together?”). Most of the Convergent Thinking questions were asked by the instructor, and in addition to requesting explanations, they sought justification for a position or asked students to draw conclusions (e.g., “What are the four major principles that you would suggest, on the basis of these assumptions?” or “Do these principles apply to all learners?”). It was not unusual for the instructor to ask probing question at this cognitive level.

Divergent Thinking questions were asked less frequently by the instructor than any other type of question (10%), and relatively infrequently by students (14%). As might be expected, there is a strong positive relationship between the Wh- broad syntactic form, that is, those asking what, why, or how, and the Divergent Thinking function (e.g., “What can educators do to foster self direction?”). This form is the most open and would be the most effective way to elicit a wider-ranging response. The instructor tended to ask Divergent Thinking questions to initiate a discussion, but those asked by students did not appear in any specific position in the discussion.

Evaluative Thinking questions were the type most often asked by both the instructor and students. This cognitive function accounted for 34% of the instructor’s and 32% of the students’ questions. One notable finding was the relationship between the Yes-no form and the Evaluative Thinking function. Evaluative questions were more likely to be asked in the Yes-no form than in any other (e.g., “Is self-evaluation more accurate than instructor evaluation?”). Although a particular form of question when asked in an ordinary conversation will elicit a like response (Quirk & Greenbaum, 1973; Stenström, 1984), this generalization did not hold true in this environment. None of the Yes-no questions received a simple Yes or No answer. In every case such a response was accompanied by a full explanation for the response. These findings contradict the views of those who argue that Yes-no questions should be avoided in an educational setting (Dillon, 1994; Hunkins, 1995). Although this position may have some merit in the K-12 context, in this online postsecondary environment, Yes-no questions neither led to a minimal Yes-no response (Hunkins, 1995) nor stifled discussion (Dillon, 1994). In fact some of the most extensive interaction arose from just such questions.

Generally speaking, the cognitive level of responses to the instructor’s questions matched the cognitive level of those questions. That is, questions asked at a Cognitive-Memory level received a response that exhibited Cognitive-Memory thinking, Evaluative Thinking questions received Evaluative Thinking answers, and so on. Although this initially appeared to be the case with students’ questions, a closer examination showed a more complex response pattern. Appeals made at the Routine Thinking level formed the vast majority of student questions that received one or more responses. These responses were themselves at the Routine Thinking level, but that Routine response was invariably followed by additional discussion at the cognitive level of the message preceding the appeal. So if Student A wrote a message at the Divergent Thinking level and concluded with a Routine Appeal (“What do you think?”), Student B might write a Routine response (“I agree”), but then follow with an explanation or justification that also exhibited Divergent Thinking. Moreover, the level of both Student A’s and Student B’s messages tended to reflect the level of the instructor’s initial question.

It would appear that the cognitive level of the question is a greater determinant of interaction than is the syntactic form. Routine Thinking questions, particularly those concerning organizational matters, garnered responses, but did not lead to interaction on the part of participants. Cognitive-Memory level questions always received a response, but never generated any interaction. It is difficult to imagine a situation where such a question would spark interaction. Because asynchronous discussion permits participants to consult their texts and other resources, the answers obtained through this type of question tend to be extremely accurate (often including source citations), and the correctness of the response is rarely open to dispute. Cognitive-Memory questions appear to serve a specific purpose: to highlight a particular aspect of the assigned readings by having a student post that material to the discussion. Convergent Thinking questions did not tend to generate a great deal of interaction either. In fact such questions usually appeared later in the discussion after participants had responded to either Divergent Thinking or Evaluative Thinking questions. Questions at these latter two cognitive levels generated the most interaction, with Evaluative Thinking questions providing the greatest stimulus for discussion.

Of the two forms of epistemic questions, referential questions were asked more frequently than were display questions. The instructor asked only seven display questions, all of which were at the Cognitive-Memory level. This stands in contrast to Gaies’ (1983) observation that display questions asked by the instructor are the dominant epistemic form. Students asked no display questions, however, and this concurs with Markee’s (1995) observation that most student-initiated questions are referential. This is not to say that participants only asked questions for which they did not have an answer. Rather, it reflects the higher cognitive levels inherent in the questions in that these questions often had many possible answers.

Transpersonal questions were not common in the interaction. Students asked seven such questions, whereas the instructor asked only one. These were always at the level of Evaluative Thinking (e.g., “Is it possible, or even desirable to separate your emotions from your actions?”). When students asked transpersonal questions, they appeared to be asking the question of themselves rather than of other participants.

More Initiating than Probing questions were found in the transcripts. The instructor was responsible for most of both types, asking 28 Initiating questions and 23 Probing questions. The number of Initiating questions asked by the instructor had an effect on the amount of interaction. When the instructor initiated a discussion topic by asking one question, or up to three related questions, student interaction was greater than when a larger number of questions was asked. The reduced interaction was most noticeable in one conference when the instructor posted a list of 16 unrelated or only loosely related questions and instructed students working in small groups to “select 4 questions for discussion.” These instructions led to a variety of responses. In the first group five students replied to one question each. Four of these questions formed the foundation for the remaining discussion. In another group six questions were answered, but only three led to discussion. In each group at least one participant appeared to interpret the instructions as they might have on a written examination. That is, they each answered—discussed—four questions, either in a single message or in four separate messages. In one group 12 of the 16 questions received a direct response. No further discussion followed from their responses to these questions. The variety of responses indicates that students may not have known how to respond appropriately to the ambiguously worded instructions.

Although the instructor asked nearly as many Probing as Initiating questions, students asked only 3 Probing questions. Probing questions could serve to stimulate interaction, but this was not always the case. It appeared to depend on whether the question was addressed to a group or an individual. In the former case, interaction was generally forthcoming. When a probing question was directed to an individual, however, it tended to develop into a two-way conversation. Probing questions asked by students fell into the latter category.

Not all questions received a direct reply. There was a considerable discrepancy between the number of instructor questions and students’ questions that went unanswered. Two types of instructor questions did not receive a verbal response. The first type was the Routine Thinking question of an organizational nature, (e.g., “Did that make sense?”). In a faceto- face classroom, such a question would probably have received some sort of confirmation, either verbally or through body language. Online, it only received a response if the answer was negative. The act of following the directions provided the confirmation that the instructions did make sense. The second type of unanswered question was distinguished by its position in the discussion. Occasionally, the instructor would ask a question in the concluding message. These questions could take any syntactic form or be at any cognitive level, but by following such a question with a phrase such as “Just something for you to think about.” it was clear that they were intended for individual reflection. Although 92.2% of the instructor’s questions received a direct reply, this was true for only 6.2% of the questions asked by students. The lack of a direct response does not, however, necessarily mean that a question was ignored. Studies of lexical references (Blanchette, in press; Howell-Richardson & Mellar, 1996; Jara, 1997) have shown that comments and questions that appear on the surface to have been overlooked do in fact form part of the fabric of the discussion. Unanswered questions were frequently characterized by one or more of those traits associated with rhetorical questions. That is, they appeared in clusters or chains, they contained such phrases as what if, and the person who asked the question often answered it.

Rhetorical questions are not a special category. They can take any syntactic form or reflect any cognitive level. Rather, they are a special use of questions, and in the transcripts they appear to have been used in three different ways. These can be described as lecturing, thinking aloud, and indirectly challenging. In each case the first speaker asks a series of questions, most of which can be read as statements in interrogative form. It is not uncommon for the questioner then to reinforce this statement by providing the appropriate or desired response. For example, “Is it feasible in our current system and with the current expectations of education to leave students who are not at this point yet, on the sidelines? In today’s system it is not feasible.” Whether this example would be perceived to be thinking aloud, lecturing, or indirectly challenging depends on several contextual factors.

First, there is a noticeable difference in the length of each type of message, with the lecture format tending to be considerably longer (as long as 2-3 pages). Although this might be considered a superficial difference, the extra length was the result of my use of strategies typical of formal rhetoric. The lecture form provides evidence of extensive research. It is organized into sections and structured in a logical sequence. The language used is also more formal than that used in other messages. Perhaps most important, there is an obvious and definite attempt to persuade the reader. Questions in this context were used either to make or to reinforce a particular point. These messages seldom received a reply, and on those occasions where a response was forthcoming, it did not include an answer to any of the question asked therein. Almost all participants used rhetorical questions to make and support arguments, but male students were more likely to use an extended lecture format. Two male students used this form more than half of the time whereas a third used it almost exclusively, writing multiple-page “lectures” containing long strings of rhetorical questions.

When thinking aloud, participants not only sent shorter messages using an informal tone, they also appeared to be seeking clarification or enlightenment. The context was often one of self-disclosure or reflection. When the questioner provided an answer to his or her own question, it generally expressed a degree of tentativeness in contrast with the tone of authority used in the lecture form. It was not uncommon for questions to be followed by such comments as “I don’t know what to make of this.” Or appeals for feedback or comments. These questions introduced new ideas for discussion and frequently served as a catalyst for higher levels of interaction among participants, although they did not necessarily receive a direct reply.

The third use of rhetorical questions, indirectly challenging, was occasionally interactive. When indirectly challenging, a participant replied to an earlier message by asking a series of rhetorical questions, but without commenting directly on any of the points in that message. This might precipitate a similar response, that is, a message containing another list of questions. Because this could go back and forth for some time, it might be more accurate to describe this form as “duelling questions.” When challenging questions were asked in response to a lecture, either the message containing these questions would receive no response or it would be acknowledged, but the questions themselves would remain unanswered. There was a third possible response to a list of challenging questions. When the questioner concluded with an explicit request for comments or feedback, often calling on the expertise of other participants, these questions, although not receiving a direct reply, did serve to stimulate group discussion.

The use of these indirectly challenging questions appeared to allow participants to disagree without engaging in direct confrontation. Participants could express their disagreement indirectly, thereby allowing the discussion to proceed without having to resolve the potentially confrontational issue. Only female participants used rhetorical questions as indirect challenges whereas male participants always expressed their disagreement with other students directly. For example, in response to a criticism of assessing stages of development, a male student replied, “I don’t think it would hurt to have your students complete a development stage profile” and continued to give his reasons for disagreeing. A female student replied with a series of questions, “Should our institutions [attempt to meet the needs of] students at different developmental levels? � Should we attempt to be flexible? Or should we � provide opportunities for individuals to work and learn at different levels?” This is not to say that female participants did not express disagreement directly, but rather that male students never used the indirectly challenging form when addressing messages posted by other students.

As is true in the face-to-face context, questions play an important role in online interaction. Nonetheless, there are many differences in how questions are used in each environment. Questions asked online draw on a more limited range of syntactic forms, but they exhibit higher levels of cognitive function. It has become evident that the latter plays a more important role in stimulating ongoing interaction. Questions phrased to elicit a yes-or-no answer do not in fact lead to abbreviated responses, nor do they discourage interaction in the online context if their content is at a higher level of cognitive functioning. Barnes (1983) suggests that professors who wish to improve their teaching may wish to analyze the level and patterns of questioning they use. This is equally true in the online environment, where questioning strategies that may have been effective in the face-to-face classroom do not achieve the expected outcomes. They may also wish to ensure that they are taking full advantage of the strengths of asynchronous communication. For example, because asynchronous interaction does not suffer from the same time constraints as does face-to-face teaching, it is possible to ask more of the higher cognitive level questions that require a longer processing time.

Students made extensive use of rhetorical questions. These questions are used to persuade others, to express thoughts, and to avoid direct confrontation when challenging the statements of other participants. So although questions at the lower cognitive levels may indicate that a student lacks information, most rhetorical questions exhibit higher cognitive functions. They are more often used to demonstrate knowledge or to construct knowledge. The instructor asked few rhetorical questions, instead using probing questions to encourage participants to expand on their ideas. When these questions are directed to the group, they are successful in stimulating further discussion provided they do not come too close to the end of the time allocated for discussion of a particular topic. Just as with face-to-face education, when asking powerful questions, it is essential to schedule sufficient time to process them (Hunkins, 1995).

This study describes the questioning behavior used in a specific environment, but the topic lends itself to further exploration. Are these behaviors characteristic of all online interaction (e.g., e-mail and listservs), or are they specific to the educational context? Would these same questioning patterns be found in a face-to-face setting where class size and subject matter were comparable, or are they a product of text-based asynchronous interaction? This study may provide some guidance for continuing research into the cognitive levels of questions and their impact on discussions in the technology-mediated environment. One of the greatest challenges in distance learning is to provide opportunities for interaction so as to engage the learners actively. Asking effective questions may be one of the best ways to meet this challenge.

This research was funded in part by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Aschner, M., Gallagher, J. Perry, J., Afsar, S., Jenné, W., & Farr, H. (1961). . system for classifying thought processes in the context of classroom verbal interaction. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois.

Barnes, C. (1983). Questioning in college classrooms. In L. Ellner & C. Barnes (Eds.), Studies of college teaching (pp. 61-83). Toronto, ON: Heath.

Blanchette, J. (1999). Textual interactions handbook: Computer-mediated conferencing. In D. Collett (Ed.), Learning technologies in distance education (pp. HB65-HB96). Edmonton, AB: University of Alberta.

Blanchette, J. (2000). Communicative strategies and the evolution of on-line interaction. Dunedin, NZ: Distance Education Association of New Zealand (DEANZ).

Blanchette, J. (in press). Participation and interaction: Maintaining cohesion in asynchronous discourse. Journal of Research on Computing in Education.

Dillon, J. (1982). The multi-disciplinary study of questioning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 147-65.

Dillon, J. (1988). Questioning and teaching: A manual of practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Dillon, J. (1994). Using discussion in classrooms. Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press.

Eakins, B., & Eakins, R. (1978). Sex differences in human communication. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin

Eastmond, D. (1995). Alone but together: Adult distance study through computer conferencing. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Edwards, S., & Bowman, M. (1996). Promoting student learning through questioning: A study of classroom questions. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 7(2), 3-24.

Ellis, K. (1993, February). Teacher questioning behavior and student learning: What research says to teachers. Paper presented at the 64th annual meeting of the Western States Communication Association, Albuquerque. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 359 572)

Ellner, L., & Barnes, C. (Eds.). (1983). Studies of college teaching. Toronto, ON: Heath.

Fischer, C., & Grant, G. (1983). Intellectual levels in college classrooms. In L. Ellner & C. Barnes (Eds.), Studies of college teaching (pp. 61-83). Toronto, ON: Heath.

Foster, P. (1983). Verbal participation and outcomes. In L. Ellner & C. Barnes (Eds.), Studies of college teaching (pp. 117-160). Toronto, ON: Heath.

Gaies, S. (1983). The investigation of language classroom process. TESOL Quarterly, 17, 205-217.

Gal, S. (1995). Language, gender, and power. In K. Hall & M. Bucholtz (Eds.), Gender articulated (pp. 69-181). New York: Routledge.

Gallagher, J., & Aschner, M. (1963). A preliminary report on analyses of classroom interaction. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 9, 183-194.

Graesser, A., & Person, N. (1994). Question asking during tutoring. American Educational Research Journal, 31, 104-37

Green, J., & Harker, J. (Eds.). (1988). Multiple perspective analysis of classroom discourse. Advances in discourse processes, volume XXVIII. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Guilford, J. (1956). The structure of intellect. Psychological Bulletin, 53, 267-293.

Herring, S. (1996). Posting in a different voice: Gender and ethics in computer-mediated communication. In C. Ess (Ed.), Philosophical perspectives on computer-mediated communication (pp. 115-145). Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Howell-Richardson, C., & Mellar, H. (1996). A methodology for the analysis of patterns of participation within computer mediated communication courses. Instructional Science, 24, 47-69.

Hunkins, F. (1995). Teaching thinking through effective questioning (2nd ed.). Norwood, MA: Christopher Gordon.

Jara, M. (1997). Analysis of collaborative interactions within computer mediated communications courses. Unpublished master’s thesis, University of London, UK.

Lakoff, R. (1975). Language and woman’s place. New York: Harper and Row.

Levin, T., & Long, R. (1981). Effective instruction. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Markee, N. (1995). Teachers’ answers to students’ questions: Problematizing the issue of making meaning. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 6(2), 63-92.

Morgan, N. (1991). Teaching, questioning and learning. New York: Routledge. Muilenburg, L., & Berge, Z. (2000). A framework for designing questions for online learning. DEOSNEWS, 10(2). Available: http://www.emoderators.com/moderators/muilenburg.html

O’Barr, W., & Atkins, B. (1980). “Women’s language” or “powerless language”? In S. McConnell-Jinet, R. Baker, & N. Furman (Eds.), Women and language in literature and society (pp. 93-110). New York: Praeger and Greenwood.

Quirk, R., & Greenbaum, S. (1973). . concise grammar of contemporary English. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Rowe, M.B. (1972). Wait-time and rewards as instructional variables: Their influence in language, logic, and fate control. Paper presented at the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, Chicago. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 061 103)

Rowe, M.B. (1987). Using wait time to stimulate inquiry. In W. Wilen (Ed.), Questions, questioning techniques, and effective teaching (pp. 95-106). Washington, DC: National Education Association. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 310 102)

Schiever, S. (1991). . comprehensive approach to teaching thinking. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Schiffrin, D. (1994). Approaches to discourse. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Smith, D. (1983). Instruction and outcomes in an undergraduate setting. In L. Ellner & C. Barnes (Eds.), Studies of college teaching (pp. 83-117). Toronto, ON: Heath.

Stenström, A. (1984). Questions and responses in English conversation. Lund studies in English. Malmö, Sweden: Liber Förlag Malmö.

Tannen, D. (1990). You just don’t understand: Women and men in conversation. Toronto, ON: Random House.

Tobin, K. (1987). The role of wait time in higher cognitive level learning. Review of Educational Research, 57(1), 69-95.

Wallace, P. (1999). Gender issues on the Net. In P. Wallace (Ed.), The Psychology of the Internet (pp. 208-232). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Waugh, M. (1996). Group interaction and student questioning patterns in an instructional telecommunications course for teachers. Journal of Computers in Mathematics and Science Teaching, 15, 353-382.

Weber, E. (1993). Varieties of questions in English conversation. Studies in discourse and grammar. Philadelphia, PA: John Benjamins.

West, R., & Pearson, J. (1994). Antecedent and consequent conditions of student questioning: An analysis of classroom discourse across the university. Communication Education, 43(4), 299-311.

Wilen, W. (1991). Questioning skills, for teachers. What research says to the teacher (3rd ed.). West Haven, CT: National Education Association Professional Library. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED 332 983)

Woodbury, H. (1984). The strategic use of questions in court. Semiotica, 48(3/4), 197-228.

Judith Blanchette is an instructional designer in the Department of Distributed Learning and an associate faculty member in the Master of Arts in Distributed Learning program at Royal Roads University, Victoria, BC.