VOL. 17, No. 1, 47-62

This article gives an account of a developing porgram of action research that started in the Open University in Scotland and widened to address strategic concerns of the UK Open University. Analysis of the impact of this action research shows its benefits for staff and for students and demonstrates how, if aligned with institutional objectives, it can become a rich resource for staff and educational and curriculum development, which provides an evidenced input from the learning experience of students.

Cet article donne un aperçu d’un programme en recherche action qui a débuté à la Open University en Écosse et qui a été élargi pour aborder la question des intérêts stratégiques de la UK Open University. L’analyse de l’impact de cette recherche action en montre les bienfaits pour le personnel et les étudiants et démontre comment, si alignée avec les objectifs institutionnels, elle peut devenir une riche ressource pour le développement du personnel, le développement éducationnel et le développement du curriculum, ce qui se traduit en un apport évident aux expériences d’apprentissage des étudiants.

This article outlines the use of action research in a project that was set up as part of the Open University’s (OU) response to major curriculum change in the United Kingdom. It describes the activities of our project group, our findings, and the wider implications for staff, students, and institutions of the use of action research projects.

When the Dearing and Garrick Reports were published in the UK in 1997, the OU in common with other institutions of higher education was faced with the demand to embed and make explicit in the curriculum the development of certain skills, and in particular the key skill of learning to learn. In the context of our University’s particular format of distance learning, we needed to shift the emphasis in the design of our course materials and of course assessments—all of which are produced centrally—to articulate and support this strand of development among all courses’ learn-ing outcomes. At the same time, we also needed to ensure that the interaction at local level between tutor and student—through correspondence tuition, tutorials, and workshops—complemented the educational design of the course materials and assessment. If the educational design of this local support were not in accord with that of course and assessment design, clearly there would be a lack of alignment that would undermine the efficacy of that design (Biggs, 1999), and affect student progress and retention.

The University decided to establish a group to tackle the implications of the Dearing requirements. This group, the Learning Outcomes and Their Assessment (LOTA) Project group, comprised representatives across all sectors involved: the schools and faculties, examinations and assessment, and so on. This article reports the activities and findings of a subproject of LOTA, the Higher Education Learning Development (HELD) project, which was set up specifically to look at the impact of this curriculum change on the nature of the interaction between student and tutor at the local level.

The HELD project group decided to focus on skills development in correspondence teaching because this is the core teaching contact between tutor and student in the OU. Students can opt into tutorials or workshops as they wish, and many choose not to. But all students who actively participate in a course submit assignments. Their tutors are contracted and trained not only to grade the assignments, but, crucially, to comment in constructive and full detail on them in a teaching dialogue. We wished to identify the kind of support from their tutor that students found effective in developing skills, and especially the skill of learning to learn, and then work out from that the implications for staff development, for student support more generally, and for the interface between centrally produced course elements and what happens at a local level.

Our starting point in setting up the HELD project was the concern that although this correspondence tuition has always been such an essential element of student support in the OU system, no systematic research had been done into the nature of the students’ learning experience in this context, and consequently no rigorously based pedagogic model was ever established. There was a wealth of good practice, confirmed as such by student success and progression and by student feedback. But this had the status of folk wisdom: effective and excellent in practice, but not underpinned by the rigorous insights into why it worked, which would enable changes to be made—as they needed to be in response to Dearing—for sound and explicit reasons.

Over the previous 10 years, the Scottish Region of the OU had been experimenting with action research as a method of gaining insights into students’ learning experience in a range of contexts, and thus enabling tutors to be more effective in responding to students’ needs. Action research had proved an invaluable tool for gathering the insights into student learning that then formed a sound basis for a more effective approach to the design of tutorials or student support in various contexts. But some of our findings had challenged the general OU folk wisdom of what constitutes good correspondence teaching and prompted us to think in this new situation that we needed to take a fundamental look at what was happening for students in correspondence tuition and not attempt merely to tweak existing practice in the direction of skills development.

Action research had also proved an ideal tool for staff development, especially at the stage where the experienced tutor can put into practice Schön’s (1983) professional self-critical reflection. Our experience with a range of action research methodologies had begun to create a toolkit of approaches that tutors can use to gain insights into students’ learning and thus collect the data to judge on an evidenced basis how effective they are and where and how they can improve.

We therefore adopted action research as a key strategy in tackling the challenges we faced in the HELD project: to find out what was effective in encouraging students’ skills development, and to create the framework within which tutors could develop the strategies and approaches to meet these needs, complementing the parallel changes in course design and assessment.

It may be useful to start from our working definitions of what we understand by the term action research and how we see this as relating to the complementary but different activities of obtaining feedback and research.

The starting point of the activities reported at the individual level is the need for the teachers to be able to engage in critical reflection on their own effectiveness and to do so on the basis of valid and adequate data. On this scale, the term more generally used might be formative evaluation. But in both cases the process is the same. The aim is to gain insight into the nature of the students’ learning experience; a tutor can then consider the raw data in the light of intended outcomes and processes and any other criteria and thus come to a conclusion about the strengths and weaknesses the process reveals as a basis for further action and improvement.

The process of critical reflection or formative evaluation can involve activities of various degrees of formality and generalizability. At one end of the spectrum lies research, the most demanding and sophisticated in that in a rough working definition, it produces through a range of rigorous methodologies outcomes of use beyond the practice of a single practitioner.

At the other end lies feedback, which can be seen as reporting opinions, or preferably data on existing practice, to enable practitioners to reassure themselves that what they planned or expected has occurred; it also leads to fine-tuning and adjustment to ensure that aims and objectives are met more effectively, preferably in time for the students who provided the feedback to benefit from the operation.

Action research in our understanding is that activity that uses, and may even devise, research methodologies to explore the nature of the learning experience for a particular group of students with a particular teacher in a particular context. It asks questions for which the likely nature of the answer is not always obvious to the questioner. It seeks change and enhancement of practice as an outcome, but not necessarily as an immediately transferable outcome in that it has been derived from a particular context with a particular group of students. It is often qualitative and illuminative rather than quantitative (Angelo & Cross, 1993; George & Cowan, 1999b; McNiff, 2001; Mills, 2000; O’Hanlon, 1996; Zuber-Skerritt, 1996).

In action research teachers can choose a form of enquiry that is appropriate to the questions that they wish to ask about their teaching and their students’ learning. The complexity of the methodology used will depend on the nature of the question being asked. But despite the deliberately restricted area of investigation and because of the rigor of this activity and the broad angle of enquiry, such action research may also produce answers that are generalizable. For this reason action research in an educational institution can prove a strong bridging link between formative evaluation on the one hand and full educational research on the other.

The background to the activities described in this article was 10 years’ exploration in the OU in Scotland of the practice and potential of action research. In the mid-1980s major change in higher education was gaining impetus, especially with the advent of new technologies that clearly had potential for student support in a distance learning institution such as the OU, but whose educational strengths and weaknesses were as yet uncharted. At the same time, the wide scatter of teaching staff in Scotland heightened the difficulty in such a dispersed organization of fine-tuning and disseminating the kinds of good practice that evolve from the explorations of individual enthusiastic staff (at the “chalk face” of) interaction with their students.

We knew that a number of tutors were experimenting individually with new and interesting approaches to student support. These approaches were often not being evaluated for their impact on students’ learning, so that the tutors themselves often had only a “gut feeling” that something worked, but no evidenced insight to enable them to explain exactly what happened and why. For this reason these new and interesting strategies could not be systematically disseminated to improve general good practice.

In the OU in Scotland, therefore, we began a policy of funding and encouraging small-scale action research projects into such innovations. Over the 10 years of this program, the activity gained in sophistication, focus, and professionalism (George & Cowan, 1999a). The ground was laid by initial work on the strengths and weaknesses of possible methodologies. The aim was to produce a toolkit of techniques that a tutor could have to hand to use easily and unobtrusively in the teaching context; that would not demand great additional expertise and time for analysis of data; and that would enable the tutor to enquire about the nature of the students’ learning experience from a range of angles.

We started at first to explore and compare the potential of a number of options:

It is impossible within the scope of this article to describe these methodologies, which are described in detail elsewhere (George & Cowan, 1999b). The conclusion drawn from this work, however, was that the various methods could each yield useful data, although of rather different types, and form the basis for beginning to build a toolkit of techniques that would enable tutors to ask a variety of questions about the nature of their students’ learning experience. Well-designed questionnaires, we believed, are useful for creating a baseline of information about students’ perceptions of aspects of their learning and a tutor’s teaching. Their limitation is that they are about perceptions. In a sense they are opinionnaires that, however well designed, mediate the actual learning experience. They may also have the disadvantage of being time-consuming to design, to complete, and to analyze. Interviews again take time outside a teaching session; they require recording and analysis, but are a valuable source of data explicitly or implicitly.

In contrast, concept maps provide data about coverage and links, with a strong emphasis on the cognitive aspect of learning, and can easily be incorporated in teaching time with little requirement for analysis or recording. IPR gives rich insights into a whole range of feelings and thoughts and is a fascinating technique to use once in a while. It is not a method to use frequently: it takes time and equipment, and it produces so many data that a tutor may take some time to absorb and assess the implications. The dynamic list of questions, however, like the concept map, is a simple technique that can be built into the design of a teaching session and produces immediate feedback on the progress of student understanding. (This method consists of flip-charting students’ queries at the start of a session, and then adding to them or scoring them out as the session progresses (George & Cowan, 1999a). We also concluded in the concept of a toolkit of techniques that a combination of techniques was often an optimum strategy. Findings from IPR or interviews with a few students, for example, could be easily triangulated for their general validity by a short questionnaire to a whole class, seeking agreement or disagreement with the key findings from the first sample.

A crucial premise in this work was that whatever method was being used, the data produced were for the tutor’s own self-evaluation. There was no question of a colleague or students passing judgment by the use of any of these techniques. The toolkit offered tutors the opportunity to decide what kind of question they wished to ask about their students’ learning, to involve the necessary people in applying the relevant approach, and then to use the data gathered for their own information as the basis for a sound self-judgment.

The focus of enquiry began with a diverse range of projects: the use of electronic whiteboards, fax machines for isolated math students, workshop design for developing students’ telephone skills, access issues for isolated math and science students, and so on. However, from this range of projects there soon developed a tighter focus for enquiry. A cluster of projects, for example, focused on correspondence tuition and the effectiveness of the tutor in providing written feedback to his or her students (Weedon, 1994, 1995). Another example is work carried out by a group of five tutors in the north of Scotland using Interpersonal Process Recall to identify strategies for the development of transferable skills in Science (Geddes & Wood, 1995; Cowan, 1998).

Apart from the increased rigor of work, there were also clear benefits for the staff and students involved. Enthusiastic staff now had tools for self-evaluation and self-development; their confidence was now justified by data, and they knew precisely where to focus efforts for improvement. Students were prompted to see the interaction with their tutor as something that they could influence—and indeed should influence—and began to take more initiative in contributing to a joint agenda or in advising their tutor what worked best for them. Feedback suggested improvement in student progress and retention.

Many of the tutors involved in this work were based in remote communities in the north of Scotland. It became obvious that another benefit was the sense of involvement and identity that this engagement created for them. Isolated tutors, like isolated students, can be paralyzed by lack of contact. This program gave them the sense of belonging and contributing to a dynamic, learning community where distance was irrelevant.

This experience and the expertise that this early experimental stage had built up laid the groundwork for the use of action research in the HELD project. But we also learned from the limitations of this early work in two important aspects. First, the Scottish action research program had benefited participating staff and students, but had not had much impact more widely in the University, although many of the findings were highly relevant to general good practice. We realized that for such activity to have institutional impact, it needed to be embedded in an institutional initiative and understood and accepted at an institutional level. Thus a framework and process would be established from the start so that our findings and outcomes would be perceived as answers to questions set and seen as relevant by the institution. The implications would then be taken up at a general university-wide level instead of only by the small group involved in the action research.

The place HELD occupied in the LOTA project ensured that our findings would be seen in this light. We reported regularly to the LOTA Steering Group, and our work was perceived and understood as an integral part of a holistic curriculum development.

The second thing we had learned from the earlier work was that the process of the action research activity was as much, if not more, important than the findings from the point of view of staff development and consequent improvements in student support. Tutors learned something from the reported work of others. But only by engaging in action research themselves did they significantly transform their own practice, becoming energized and enthused by the insights they gained into their students’ learning and genuinely developing the habit of critical reflection and self-development. We decided, therefore, that we must engage as many tutors as possible in the HELD action research rather than working with a small group that would merely report findings.

The program was coordinated by a small steering group and involved 22 tutors, each with a group of 6-8 students, over the two years of activity, 1999 and 2000. We focused on the experience of students early in their OU careers on four Level One courses: in the first year of the project in science (S103), and arts (A103); and in the second year in math (MU120) and health and social work (K100). All these courses explicitly include skills development as learning outcomes, although to varying degrees.

We chose to use the simple methodology of structured interviews that had proved useful in our previous work and easy for tutors to learn how to use (Lee, 1997).

Because the intention in selecting two different courses in the second year was to test and extend the findings from the 1999 iteration, the same methodology was used throughout. The tutors taking part in the first year were briefed by a tutor who was already an experienced action researcher. These tutors were also interviewed at the beginning of 2000 about their plans for facilitating skills development in 2000, and the outcomes of these interviews were used in briefing the second wave of tutors taking part in the action research in 2000.

The geographic range of the enquiry was also extended in the second year, with three different geographical regions of the OU involved each year. In the first year the 10 volunteer tutors across the chosen regions, with their student groups, conducted their action research enquiries at three points in the year when students had just received back their assignments with their tutor’s grading and comments. In year two 12 tutor groups were involved in only two iterations of enquiry (due to circumstances).

The tutors worked in pairs, one from each of the two courses covered and each acting as enquirer with the partner’s students. Each enquirer had little or no knowledge of their partner’s subject area, nor of the specific skills demanded by that particular course, so that they would remain focused on their generic enquiry and not be tempted to be sidetracked into discussing the course or subject itself.

The medium of contact between the enquirer and the student group was audioconferencing, a reasonably familiar medium to tutors and students and the only way of conducting such a group enquiry with widely scattered students. The enquirer would use the same semistructured questions each time, asking which comments the students found most useful and least useful—and why—in facilitating the development of the skills they needed. The enquirer then reported back to his or her partner on the clear understanding that he or she was reporting data to inform the partner’s self-evaluation (as well as the project team). At the end of each year the tutors set time aside for reflection and reported to the project manager what they had learned from taking part in the action research. In addition, tutors and students were interviewed during the following year to find out what, if any, impact participation in the project had had on their practice.

The Action Research Group followed up the students who had been involved in the early stages of this project first, to confirm some of the general findings, and second, to discover if they were conscious of having derived any long-term benefit from this involvement (Wood, 2001a).

A number of general points arose in the first year and were further supported in the second. The activity of action research itself improved the performance of both students and tutors. It proved of significant value to all involved—it challenged and stretched them, it was fun and enthusing, and it made a difference. It engaged them in meta-cognition—although they did not recognize that this was happening.

From the action research findings, tutors learned how much more important to students than they had realized is the affective aspect of building confidence; confidence and competence develop side by side, and one feeds the other:

think about each person to whom I’m writing and make the remarks as personal as possible, especially when I see improvement from one TMA (assignment) to the next. make more use of comments like “good point” and “you’re on the right lines,” rather than reserving praise for outstanding good work only. encouraging remarks keep you going. [They are] not just mealy-mouthed praise—the encouragement goes hand-in-glove with explaining why something is right, and that’s important information.

Tutors also realized the importance of being more purposeful and proactive in offering systematic advice on developing the skills, for example, of analyzing and answering questions, presentation of ideas, and time management in general (as opposed to comments on single instances):

be very specific—e.g., rewrite an introduction, using the same material as the student and showing them how to tweak it to improve. comment on skills not taught explicitly, but needed at certain points on the course: e.g., time management before the exams.

Interestingly, tutors found that the nature of the support they should

provide in the affective area differed with the stages of the academic year. For example, students needed general encouragement at the start of the year, but would often prefer to have less of this and more focused comment on what was right and why, what was wrong, and how to improve toward the middle and end of the year.

Issues of academic literacy became apparent, with the need for tutors to identify and to address these explicitly, especially in the early stages of a course and with students who were beginning study with the University. Each faculty and discipline has its own language and mindset, which can create considerable and often unrecognized barriers for students.

At the same time, it is important to note that as we suspected at the start, these insights could not just be reported to the second group of tutors for them to benefit. They had to reconstruct their own approach and style through the process of engaging themselves with the students in the action research activity:

I � must move to being a facilitator rather than assessor, despite still having an assessment role.

I’ve developed a more abstract view of skills � it’s interesting to see how much there is in common between disciplines � and I’ve valued working with colleagues in this way.

It gave the students pause for reflection and deepening insight into

their own learning with positive results. They saw that they themselves had a contribution to make to a relationship that centers on learning and teaching; and that the more active and questioning and self-aware their contribution was, the better and more satisfying their learning would be:

I can see I’ve come a long way since the start of the year, in the way I study, etc. I’ve a long way to go yet. My self-assessment was spot on: I knew it wasn’t as good as the others, but I will get there.

They saw how their work differed validly and usefully from the learning

of other students (e.g., in identifying the strategies they found useful), while reassuringly it was the same in that they were all struggling with similar challenges. Remarks such as “everyone found this difficult” were valued, and tutors were told: “say ‘this is good because �”’ A student commented, “It was good to know I could share problems and to realize that many others also found difficulty. I felt I was not suffering in isolation.”

In many cases, although students realized that their familiar methods of working were not effective, they did not beforehand have the confidence to work in unfamiliar ways and to experiment:

I am aware that my study technique has become more efficient and focused.

It has helped to talk through ideas.

This has been a year for experimenting. Now I know the way I do it, and that’s OK.

The follow-up enquiry (Wood, 2001b) confirmed the general findings, with a clear emphasis on the value the students set on being known to their tutor as an individual even above earning praise. Of the students 34% perceived that the experience of involvement in the action research had changed how they approached their work the following year. The process had encouraged them, given them time to think about their methods of working, and drawn their attention to the importance of skills development in their own progress.

The findings set a number of challenges for more effective and integrated design of assessment and of the tutor-student interaction. For example, for the students in general:

Some of the issues raised were for the attention of course teams. For

example,

Issues emerged for University policy and practice in relation to tutors.

For example,

Our experience throughout both stages of using action research has been that it is a powerful instrument for change and for quality enhancement for students, staff, and the institution.

Though our sample of students was relatively small, tutors uniformly reported an improvement in grades and in students’ ability to tackle learning problems and make significant progress. Involvement in action research prompted students to reflect systematically on their own learning processes. Although reflection is increasingly being built into curriculum design in any case, action research takes its benefits one stage further. The process strengthens and deepens the learning relationship between tutor and student, with the result that the dynamics of responsibility shift and students genuinely begin to play a more active part in the learning-teaching interaction. The tutor learns to be a better facilitator, but the students too become facilitators of their own learning, consciously and effectively.

For an individual tutor, we would argue that action research is fast becoming an essential element of teaching professionalism. We now work in the culture of the self-critical reflective practitioner who habitually reviews his or her practice. Such reflection to be rigorous must be based on a sound methodology that produces the data that the teacher can use to match performance against benchmarks and come to evidenced conclusions about strengths to build on and weaknesses to eliminate. Such rigorous judgments can be used for personal self-appraisal or as a sound starting point for the more formal engagement of appraisal by a line manager, head of department, or external audit.

In our experience tutors involved in action research develop justified confidence because their self-judgment of strengths and weaknesses is soundly based. Their enthusiasm and motivation are enhanced by the sheer excitement of the insights into the processes of student learning. They gain the sense of always being at the cutting edge, at least in relation to their own practice, which must be at the heart of good continuing professional development; and they have the satisfaction of seeing their students’ motivation and effectiveness increase in step with their own.

In the face of change, action research is an invaluable tool for tutors to find how effectively the students have adapted or transferred the skills of dealing with the previous context: what the students’ learning experience is and how well they are responding to it. To be effective in learnercentered teaching, teachers must know what is happening for their students; and action research is the way to find out, simply and yet soundly.

More generally, the practice of action research potentially changes not only the quality of the experiences of teaching and learning, but also the nature and role of staff development, at least in its later stages when it becomes continuing professional development.

The induction program for new staff or staff new to a role will always remain. This, however learner-centered, is necessarily modeled on the assumption that it is the staff responsible for the activity who have the experience and expertise. But once experienced teachers are given a role where through rigorous reflection on their own practice and their students’ learning experience, they have a valid voice with which to influence institutional and curriculum development and continually to create and recreate their own identities as teachers, then this is no longer traditional staff development. The boundaries between educational and staff development become blurred. The reflective practitioner (Schön, 1983) has been let loose on an institutional scale. Our belief is that this can only be for the good in that anything less is professionalism manqué. But there may be certain institutional discomforts as well. We are used to challenge from research; this change will provide challenges to the traditional educationalists and educational developers as well. At the departmental or institutional level, action research is also a tool that cannot be neglected.

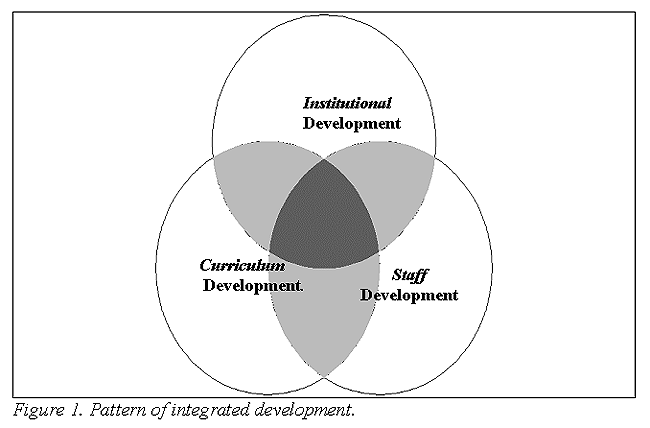

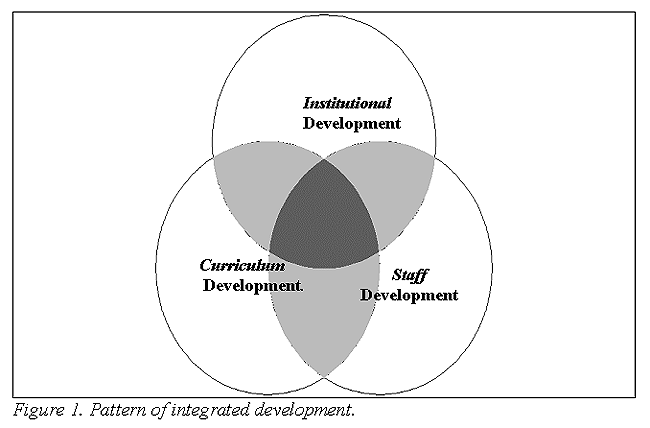

As Cowan (1978) argues, the most effective development occurs at the intersection between curriculum, institutional, and staff development (the dark area in Figure 1). Only when institutional strategy is thought through into the details of what it implies for curriculum development and staff development will it be truly effective. Yet to complete the feedback loops and review effectiveness, it is necessary to gain data from each of these areas and to consider them on the same holistic basis. If the data of the actual student experience is missing, then there will be a vital gap in the basis on which this review is carried out.

From our experience on the HELD project, we would argue that institutional feedback as usually practiced is not sufficient. This can provide broad-brush feedback at a general level. Significantly, UK Higher Education planning documents currently speak of seeking “student opinion,” and often refer to the use of questionnaires. They are quite correct in that opinion is exactly what this approach will collect. But opinion is no more and no less valuable in this matter than it is in other academic arenas. The various methodologies of action research, on the other hand, document the effectiveness of teaching and curriculum design from a variety of angles, providing the data that are needed to answer the questions Higher Education should be asking about the actual student learning experience. Without such evidence, any judgments lack rigor and validity. And if the voice from the interface between tutor and student is ignored, attention will not be paid to the critical student-centered dimension of any development.

However, as our experience suggests, action research needs to be conducted within a framework of institutional processes to have its full im-

pact on the quality of the institution’s learning and teaching. It will certainly benefit the individual tutor and students as an independent activity. But as an activity built into the procedures and processes of a department or institution, it is a vehicle for quality enhancement through student and staff development, it gives policy-making bodies access to a unique and vital source of data, and it contributes to a holistic response from the institution to challenges: as the HELD project has contributed to the OU’s response to Dearing’s challenge.

Angelo, T.A., & Cross, K.P. (1993). Classroom assessment techniques (2nd ed.) San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Biggs, J. (1999). Teaching for quality learning at University. Milton Keynes, SRHE and Open University.

Cowan, J. (1978). Patterns of institutional development. Paper presented at the Staff and Educational Development Conference, Manchester.

Cowan, J. (1998). Professional development for teachers— Learning with our students? Uniscene European Workshop, University of Salford.

Geddes, C., & Wood, H.M. (1995). Evaluation of teaching transferable skills in science (Project report 1995/1). Edinburgh, UK: Open University.

George, J.W., & Cowan, J. (1999a). Ten years of action research: A reflective review, 1987-1997. Edinburgh, UK: Open University internal publication.

George, J.W., & Cowan, J. (1999). A handbook of techniques for formative evaluation. London: Kogan Page.

Kagan, N. (1975). Influencing human interaction: Eleven years with IPR. Canadian Counsellor, 9 (2), 74-97.

Kelly, G.A. (1995). The psychology of personal constructs. New York Prentice-Hall.

Lee, M. (1997). Telephone tuition report (internal report). Edinburgh, UK: Open University in Scotland.

McNiff, J. (2001). Action research. London: Routledge Falmer.

Mills, G.E. (2000). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher. New York, Merrill.

O’Hanlon, C. (1996). Professional development through action research. London: Routledge Falmer.

Perry, W. (1970). Forms of ethical and intellectual development during the college years: A scheme. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Schön, D.A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. New York, Basic Books.

Weedon, E.M. (1994). An investigation of the effect of feedback to students on TMAs (Project report 1994/5). Edinburgh, UK: Open University.

Weedon, E.M. (1995). An investigation into using a self-adminstered Kelly analysis (Project report 1995/2). Edinburgh, UK: Open University.

Wood, H.M. (2001a). Higher education learning development: Action research report. Edinburgh, UK: Open University.

Wood, H.M. (2001b). Higher education learning development: Follow up action research report. Edinburgh, UK: Open University.

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (1996). New directions in action research. London: Routledge Falmer.

Judith George is Deputy Scottish Director in the Open University. She has worked particularly to develop the patterns of support for staff and students in the more remote regions of Scotland. She researches and publishes on the impact of technologies in learning on assessment and on educational development issues. She is currently involved in projects on access to higher education for disadvantaged adults and on learning development.