Determinants of the Study Patterns of Female Distant Learners: An Evaluative Survey |

VOL. 6, No. 2, 58-63

An evaluative survey of the study habits of female distant learners in Nigeria suggests that home environment, household chores, maternal responsibilities, isolation, and concentration problems constitute barriers to private learning. The emerging pattern of the study habits appears to be a response to these major barriers. The paper notes the impact of these barriers as evident in several learning problems. Their implications for female education, particularly in areas where women are poorly represented, are discussed. Steps to enhance the education of women as a disadvantaged group are suggested and are seen as developmental measures for distance education.

Cette enquête, qui évalue les habitudes d'apprentissage des étudiantes à distance au Nigéria, suggère que l'environnement du foyer, les tâches domestiques, les responsabilités maternelles, l'isolation, et les difficultés de concentration constituent des barrières à l'apprentissage privé. Le modèle des habitudes d'étude qui émerge semble être une fonction de ces barrières principales. L'article mentionne que la présence de ces barrières se révèle au cours de plusieurs difficultés d'apprentissage. Il discute aussi de leur implication pour l'éducation des femmes, particulièrement dans les domaines où les femmes sont mal représentées, et suggère des démarches pour améliorer l'éducation des femmes en tant que groupe désavantagé, démarches qui sont considérées comme des mesures de développement de l'édu-cation à distance.

A project conducted to evaluate the study habits of female distant learn-ers in Nigeria suggests that the behavioural pattern that emerged is largely a function of various factors, many of which correlate closely with the learners' home-related duties or tasks. Together, these tasks make considerable demands on the learners, often at the expense of study time. Inadequate time to study has remained an intractable barrier to many learners (Kaeley, 1980; Holmberg, 1987; Mutanyatta, 1989). Moreover, when the students are women, most of them with family and children, the demands placed on them become better appreciated.

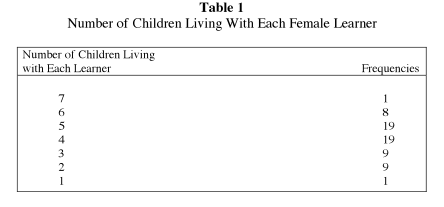

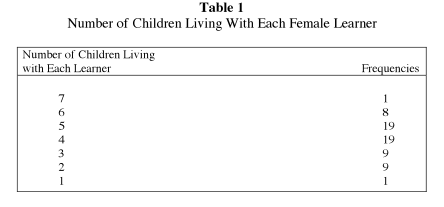

Eighty-four (n = 84) adult female students of the Nigerian Certificate in Education by Correspondence (N.C.E. cc), Division of Distance Education, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, were involved in the questionnaire-based interviews. Eighty-two percent (n = 69) were married; 96% (n = 66) of whom were living with children. shows the number of children living with each respondent.

Of the total population of 84, 11% (n = 9) were single and none of these women had a child living with her at home, 2% (n = 2) were either separated or divorced, and the family status of 5% (n = 4) was unspecified.

The N.C.E. cc is a post-secondary, two-year program leading to a Bach-elor's degree in Education from the Ahmadu Bello University. The correspondence course combines face-to-face classroom teaching with distance learning. All learners (males and females) are practising teachers and most come from the primary school system.

Two approaches were used to gather data regarding the learners' daily study-times (Monday to Friday). The first, referred to as the specific response approach, required respondents to state for each day:

When information on the specific response section was analyzed, there appeared to be two periods during the day when women typically were able to study. The first occurred between 3 a.m. and 7 a.m; the other between 2 p.m. and 12 midnight. A total of 109 responses was recorded in this section, out of which only 26% (n = 28) were made under the morning session.

Responses indicated that morning study sessions began between 3 a.m. and 6 a.m. and ended between 4:30 a.m. and 7 a.m., as seen in Table 2.

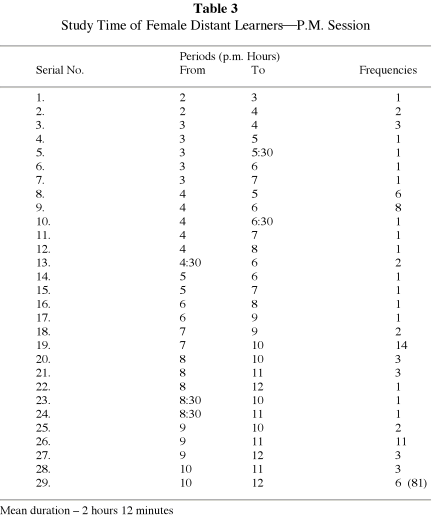

Far more women were able to study in the evening. As shown in Table 3, however, the length of evening study sessions varies from one to four hours, with more than 56% of the sample typically studying for approximately two hours. This figure is in keeping with the calculated mean of 2 hours 12 minutes reported in Table 3.

It will be recalled that in the direct response section of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to indicate the total number of hours they studied each day. The mean daily figure according to this direct response was 2 hours 40 minutes. However, when the mean is computed for

Under a partly guarded and partly free response setting, learners were asked why they studied during the time indicated. The responses showed that at the time recorded:

It is worth noting that noise was reported to be a major problem for these women and it was for this reason that the most popular time to study was from 10 p.m. to midnight.

In the "free response" section of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to comment on the problems they encounter while studying. Typical among these were:

Maternal responsibilities, family and home chores, and the inadequacy of many homes as the major study base for the home-bound woman are among the barriers that the female distant learner contends with. When it is recalled that most N.C.E. cc learners are primary school teachers whose teaching day ends as early as 2 p.m., the 2 hours 10 minutes daily study time may appear rather short, unless, of course, one is aware of the extent to which the barriers discussed above affect the time these women have available to them.

Given this situation, measures specially designed to enhance women's participation in education are needed. Distance education provides opportunities to meet these needs. By its strategies and models, distance education allows unique opportunities for learners to combine education with other socioeconomic pursuits.

Such measures, however, will not be as effective as they could be unless women and their particular needs are addressed in distance education initiatives. The need for a quiet place to study is a case in point. Setting up regional centres is one way to meet this need. Such centres would also tame "the tyranny of distance" by providing communication exchange services. Such centres could also be used to conduct face-to-face classroom sessions. Many respondents felt that this would mitigate the effects of isolation associated with limited telephone service and an unreliable postal system. A further function of the regional centre could be to translate these modules into the predominant language of the area it services.

Many questions need to be asked, however, before such centres are established. These include:

Given the many distractions that women learners encounter, it is also recommended that courses be presented in modules and that upon successful completion of each module, a certificate of merit be awarded. It is anticipated that this system would serve a motivational purpose that would increase the likelihood of course completion.

If the foregoing suggestions were implemented, it is predicted that women would not be the only beneficiaries. In the long run, there is potential for the changes noted here to benefit all distance learners.

Holmberg, B. (1987, January). Goals and procedures in distance education. ICDE Bulletin, 13, 26–31.

Jenkins, J. (1976). Editing distance teaching text. London: International Extension College.

Kaeley, G. S. (1980). Distance teaching at UPNG: An evaluation report of the matriculation studies 1978–9. Port Moresby: University of Papua, New Guinea.

Kaye, A., & Rumble G. (Eds.). (1981). Distance teaching for higher and adult education. London: Croom Helm/Open University Press.

Mutanyatta, J. (1989). Formative evaluation of distance education: A case study of the certificate in adult education at the University of Botswana. Journal of Distance Education, IV(1), 36–45.

Perraton, H. (1973). The techniques of writing correspondence courses. Cambridge: International Extension College.

Rowntree, D., & Connors, B. (Eds.). (1979). How to develop self-instructional teaching. Milton Keynes: The Open University.

Eno Effeh has taught and written individualized study materials in Geography and Social Studies for the Nigerian Certificate in Education by Correspondence (N.C.E. cc) program. He has been editor and co-ordinator of the Teacher In-Service Education Program (TISEP). Currently he is a lecturer in Geography and Social Studies at the Federal College of Education, Zaria. He also serves as co-ordinator, Zaria writing zone for the Centre for Distance Learning and Continuing Education at the University of Abuja, Abuja, Nigeria.