VOL. 27, No. 2

The purpose of this exploratory investigation was to share the strengths, challenges, and tensions of using Facebook in an undergraduate nursing program. The observations presented have emerged from information shared by study participants and the professional insights of the three researcher-authors who represent perspectives from nursing, education, and technology-enabled teaching and learning. The theoretical framework used to guide the study was Drexler's (2010) Networked Student as well as ideas based on work by Siemens (2010) and Downes (2012).

Findings suggest that use of Facebook in professional programs such as nursing provides an opportunity for the modeling of professional behaviour by students and teachers. However, concerns about privacy, misinformation, and a lack of professionalism are also present in the discussions of Facebook in professional programs. As a learning strategy, Facebook is recommended when pedagogical benefits are anticipated and clear and transparent guidelines regarding its use have been established by the user group.

It is respectfully acknowledged that there are many social media options available to students and teachers to support learning in a professional program. Facebook, however, was the focus of this study given its unique prevalence among university students at the present time. The paper is a first step in looking at how Facebook and other social media experiences may play a role in supporting learning in professional programs offered by universities.

Le but de cette enquête exploratoire a été de partager les points forts, les défis et les tensions liés à l'utilisation de Facebook dans un programme de premier cycle en sciences infirmières. Les observations présentées ont émergé des informations partagées par les participants à l'étude et les connaissances professionnelles des trois chercheurs-auteurs qui représentent les perspectives de soins infirmiers, d’éducation, et d’enseignement et d'apprentissage par outil technologique. Le cadre théorique utilisé pour guider l'étude a été celui de l’étudiant en réseau de Drexler (2010) ainsi que des idées basées sur le travail de Siemens (2010) et Downes (2012).

Les résultats suggèrent que l'utilisation de Facebook dans les programmes professionnels tels que les sciences infirmières fournit une opportunité pour la modélisation de comportement professionnel par les étudiants et les enseignants. Cependant, des préoccupations sur la vie privée, la désinformation et le manque de professionnalisme sont également présents lors des discussions de Facebook dans les programmes de formation professionnelle. Comme stratégie d'apprentissage, Facebook est recommandé lorsque les avantages pédagogiques sont prévus et que des directives claires et transparentes concernant son utilisation ont été établies par le groupe d'utilisateurs.

Il est respectueusement reconnu qu'il y a plusieurs options de médias sociaux disponibles aux étudiants et aux enseignants pour appuyer l'apprentissage dans un programme professionnel. Cependant, Facebook était l'objet de cette étude compte tenu de sa prévalence unique parmi les étudiants universitaires à l'heure actuelle. L’article est un premier pas pour jeter un regard sur la façon dont les expériences de Facebook et d’autres médias sociaux peuvent jouer un rôle dans le soutien de l'apprentissage dans des programmes professionnels offerts par les universités.

Today, educators are challenged by their administrations as well as their students to take ‘learning beyond the classroom’ and to use multimedia and Internet-enabled social applications in order to engage with students and, ideally, inspire learning. As a result, 21st century teaching and learning is characterized by several tensions. These tensions include but are not limited to the following: the need for teachers to find creative ways to capitalize on digital and networked technologies, for which they have little or no training; teachers’ apprehensions that they are not as important as in the past; and the fact that the classroom can be an ‘anywhere any time any how’ reality. Other tensions pertain to pedagogical shifts away from transmissive to constructivist and connectivist approaches as well as the task of connecting students with other students to participate in iterative knowledge building and the development of communities of practice (Wenger, 2004; Wenger & Lave, 1999; Wenger, McDermott, & Synder, 2002). The changing configuration of the learning setting is another issue. In days past, distance education was clearly defined as involving geographic distance from the main campus. Today, distance education is as much about time constraints and busy lives as it is about kilometers from universities. Blended learning and flipped classrooms are further variables in the decisions that educators are making about course design and delivery (Carter & Graham, 2012).

Still other tensions focus on the time and resources required to ensure that technology in learning does inspire student learning (Salyers, Carter, Antoniazzi, & Johnson, 2013); the demands of 21st century curricula with different levels of differentiation; accreditation standards that may or may not embrace technology-enabled learning; limited budgets; information security; and student safety. Confounding this situation is the uneven technological landscape that exists within education and the reality that social and mobile technologies are transforming how students learn about and interact with the world (Clifton & Mann, 2011).

Of all the educational possibilities available, the one that has generated greatest distress among educators is social media and, in particular, Facebook. While educators would be hard pressed to deny the potential of Facebook in other aspects of social interaction, using it to facilitate learning is a subject of some debate. It is particularly an issue among those who teach in professional programs such as nursing and education in which professionalism is part of curricula and an expectation of regulatory bodies. As an example, in the accreditation requirements set by the Canadian Association of Schools of Nursing (2013), all nursing programs are assessed for evidence of formal and informal learning about professionalism and nursing as a professional practice field. At the same time, there are also teachers in colleges and universities, such as the researcher-authors who are interested in exploring the pedagogical value of Facebook and who recognize that many students are engaged in what Brocade (2011) calls e-living. According to some researchers, when used responsibly, social media can foster significant levels of student engagement and assist students who are becoming professional in addition to many of their teachers who are adapting to today’s world (George, 2011). At the same time, part of being a professional in today’s world involves making choices about the appropriate use and non-use of social media.

Given the above, the purpose of this study was to document the strengths, challenges and tensions of using Facebook in undergraduate nursing programs and to incite conversations about the appropriate use of social media in professional programs. On a practical level, study findings will be important to educators interested in understanding social media as a means of engaging with students and possibly developing communities of learning in the tradition of Wenger (2002). Importantly, according to Wenger, robust communities of practice may actually inspire participants. Hypothesizing, it may be possible that effective use of Facebook by students and teachers may lead to situations of inspired learning.

As context to this study, the following literature review provides an overview of how social media is presently being used for health purposes and in health education settings. This consideration of the literature sets the stage for the aforementioned use of Facebook in nursing programs. Moreover, it identifies the key issues associated with its use in professional education in general.

According to Statistics Canada (2012), the number of Canadian households with home Internet access increased from 79% in 2010 to 83% in 2012. Many households access the Internet using multiple devices. The most notable increase occurred in the use of wireless handheld devices, with an increase from 35% in 2010 to 59% in 2012. Likewise, in countries where access to the Internet is limited, there has been rapid growth in the use of mobile devices to access information (McNab, 2009). Based on what is known about the increased popularity of social networking and growth in mobile technologies since the time of these statistics, it should come as no surprise to learn that, according to Greene and Kesselheim (2010) and Lane and Twaddell (2010), approximately 60% of persons seek health information from the Internet before going elsewhere. Similarly, 45% to 57% of users report sharing their health care knowledge via social media. Other research points to the use of the Internet and social media as tools for gathering health information and promoting health strategies, particularly among adolescents (Weaver-Larisey, Reber, & Paek, 2010).

Communication and educational technologies are also invading other aspects of health care. As examples, many health-related offices have gone paperless just as email is increasingly being used to book appointments. Eytan et al. (2010) have noted that some physicians use social media to build trust, promote management of health and wellness, and disseminate information to their patients. The growth of telehealth and telemedicine has also affected how many patients receive care and how health professionals interact with each other and pursue their continuing professional development. Defined as interactive health-focused services that bridge physical distance through technology, telehealth is a growing field in Canada. As an example, the Ontario Telemedicine Network (OTN) is one of the largest telemedicine networks in the world, delivering clinical care and continuing education opportunities for health professionals and patients using live, two-way videoconferencing and other technologies. For 2010, it has been estimated that nearly 3,000 health professionals at more than 925 sites used OTN to deliver care (Carter, Muir, & McLean, 2011).

Although the use of social media in health contexts appears to be increasing, questions remain about users’ skills in assessing information for quality and appropriateness. Weaver-Larisey, Reber, and Paek (2010) report that middle school students do not tend to differentiate among advertising, entertainment, and news content when they evaluate information. In other words, while adolescents are likely to seek health information via the Internet including social media, they are not likely to assess this information critically. Advertising on social media sites has the potential to lead to negative consequences for younger students without access to teachers and/or responsible adults to identify potential dangers and choose appropriate interventions. Currie (2009) reported that social media has been used to share information about everything from disease outbreaks to weather emergencies. However, because there are few or no controls on who posts or distributes information, there is no way to identify potential hoaxes and misinformation.

The ubiquity of modern technologies has led to new thinking about the potential of social media for more formal approaches to education. According to McNab (2009), some educators report successful incorporation of technologies and social media into their courses and programs. Reported benefits include support for different learning styles, creation of flexible learning environments, and provision of portable and interactive means of global knowledge building (McNab, 2009). Carter and Graham (2012) have also identified many instances of successful use of educational technologies in face to face and remote classrooms in their university where professional education is a principal mandate.

Use of e-technologies and social media tools such as podcasts, webcasts, interactive modules, and networking technologies in educational settings has also been identified by post-secondary students as preferred ways of learning (Mitchell, 2008). As a result, colleges and universities have incorporated e-technologies into a wide cross-section of teaching and learning settings. Direct educational interventions such as desktop videoconferencing, and instant messaging are used to enable synchronous communication and personal learning. These same technologies benefit the institution in other ways as well. Most notable are the opportunities to provide information to potential students and their families and to facilitate continuous engagement with peers and educators (Gorham, Carter, Nowrowzi, McLean, & Guimond, 2012).

Although the growth and potential of social media and e-technologies are indisputable, the combination of social media, teaching and learning, and subject areas where there may be some risk to personal safety and/or requirements such as professionalism can generate controversy. By contrast, supporters (Brady, Holcomb, & Smith, 2010; Siemens & Conole, 2011; Veletsianos, 2010) point to the capacity of social media to enable social presence. The contention is that social presence leads to reduced feelings of detachment and greater depth in the learning experience than otherwise (Anderson, 2005).

As suggested earlier, teaching and learning today is a dramatically different landscape than 20 years ago. Learner-generated content, informal interactions, short messages, and computer-mediated interactions are the norm for digital age learners (Wiske, 2011). Social media adds yet a further dimension. Considered together, these realities challenge existing pedagogies as learners shape their identities by sharing information and participating in the process of building new knowledge. As learners interact, they receive feedback from their environments, other learners, and their teachers. These interactions may be synchronous or asynchronous in nature and facilitated through text, voice, graphics, video, shared workspaces, and combinations of these elements.

Fundamental to 21st century learning is connectivist pedagogy with its emphasis on connections. Siemens (2010) has described learning as a process that occurs within an environment of shifting core elements that is not entirely under the control of the individual. Given this understanding of learning, learning is a process of connecting specialized nodes or information sources. Similarly, according to Downes (2012), learning consists of networks of connections formed through experiences and interactions with a knowing or knowledge community.

Pulling on these ideas, the framework used in this study is the Networked Student Model (Drexler, 2010). According to Drexler, the “Networked Student” participates in several activities: the act of making contacts with others, information management, synchronous communication, and really simple syndication. The first activity is what distinguishes Web 2.0 from its previous iteration—the capacity to connect with colleagues, friends, classmates, and others through programs such as Facebook for purposes of socializing, sharing, and, learning. In the act of information management, the user engages actively with the ideas and content he or she is accessing, making decisions about relative value and prioritizing it in relation to other data sources. Asynchronous communication refers to contributions made to virtual discussion boards, blogs, forums, wikis, and other web spaces which offer the participant place and time to share thoughtful reflections (Dickieson, & Carter, 2010; Carter, Rukholm, & Kelloway, 2009). Really simple syndication refers to information that comes to the user through regularly updated web feeds.

In this study, the participant is a networked person who may also be a networked nursing student. While he or she aspires to grow in individual knowledge, the person does so through connections and exchanges with others. As such, he or she may use social media in different settings including informal personal spaces such as the home and the more structured setting of a classroom. More specifically, the student accesses and structures information (information management, really simple syndication) and connects with people (contacts made, synchronous communication) (Drexler, 2010).

Some scholars have argued that technology changes how people learn (Tapscott, 2008). Others suggest that learning is the same as it was in years past—a situation that involves dedicated time on task and access to expert knowledge transferred from the teacher to the student (Bullen, Morgan, Belfer, & Qayyum, 2009; Bullen, Morgan, & Qayyum, 2011). Research evidence based on work by Margaryan, Littlejohn, and Vojt (2011) do not “support popular claims that young people adopt radically different learning styles [in technology-supporting learning settings]” (p. 429).

In summary, Drexler’s (2010) ideas about networked students and work by Siemens (2010) and Downes (2012) comprise the theoretical position used in this study. The study is also grounded in ideas about possible changes in how students learn in today’s web-based world.

The design of this mixed methods exploratory descriptive study included an online survey, face to face interviews, and the reflections of the members of the research team. This team included three university teachers in the professional programs of undergraduate nursing and education.

This methodology was selected based on the area of investigation: perceptions about using social media to enhance learning in a professional program. Although other methodologies might have been used, this one provided the greatest level of congruence between the purpose of the study and the participants as users of Web 2.0 technologies. Use of a mixed methods design enabled the researchers to develop an initial picture of the participants’ views while interviews were used to validate and explore these views. The inclusion of reflections by the researchers based on practice-based experiences adds a unique dimension. The researchers are also learners in this new world of social media. In this sense, this investigation represents a reciprocal learning experience.

The study was based on the views of a small sample and, therefore, generalization of findings is not possible. Still, the insights comprise a stimulus for conversation and a starting point for further investigation and collaboration. The study received ethical approval through the Research Ethics Committee at the involved institution.

As noted, data were collected in three ways. The first data collecting strategy was an open ended question-based online survey. Video interviews followed completion of the survey. Finally, the researcher-writers engaged in self-reflection based on their experiences teaching in professional programs at the university level.

A link to the survey was posted in several places: within a private Facebook group, on a public Facebook page, on Facebook walls, and within the communication forum of the learning management system of one post-secondary institution. Conducted over a short period, the survey was completed by ten persons. No demographic data were collected. In addition, four participants volunteered for video interviews and consented to have their ideas shared through YouTube videos. Notably, one of the researcher-authors, in addition to having experience with Facebook, has considerable experience in using YouTube for learning and knowledge translation purposes. The idea of sharing the perceptions of the participants via YouTube was important; since some teachers search YouTube for teaching and learning resources, they might discover the findings. The research team also determined that it was important to share study findings in conventional and less conventional ways. Signed consents for posting the participants’ videos on YouTube were collected.

In both the survey and the interviews, three open-ended questions about the use of Facebook to support learning were explored:

As noted previously, participant responses to the above questions became the basis of videos that are now available on YouTube (Figure 1). The following areas are highlighted in the videos:

Figure 1. Link to Video Summaries of Interviews

The analysis technique was based on work by Miles and Huberman (1994). Miles and Huberman recommend three concurrent flows of activity: data reduction, whereby participant responses are coded and sorted into individual clusters of varying main themes; data display, whereby participant responses are organized, compressed, and assembled into various tables and figures which permits conclusions to be readily visible and easily drawn; and conclusion drawing/verification, whereby conclusions are verified and validated through the repeated readings, discussion, and debate.

Survey and interview data were repeatedly reviewed to familiarize the research team with the data set. Then, all survey responses and interviews were analyzed through techniques of coding and labeling, grouping according to similarities, and mind mapping.

Conflicting perceptions among the researchers were resolved through discourse, with final decisions requiring agreement between at least two of three researchers. In the event of three contrary views, ideas were removed from the data file. Once the data were organized, they were reexamined and grouped into dynamic categories representing themes. Subsequently, they were represented visually in working tables which informed the content development of the videos.

The research team met several times via teleconference and used Google Documents to reflect on the findings and to identify their own insights based on experience with the participants’ insights. The participants’ views are presented discretely in the Findings section. Whenever the researchers’ views are included such as at select points in Discussion and Final Thoughts, they are clearly designated as the views of the authors as teachers.

Three categories of findings emerged. The first category outlines the challenges to professionalism and other risks that may exist when Facebook is used in a nursing program; the second focuses on using Facebook to learn about professionalism in a nursing education program. These categories of findings offer insights into research questions 1 and 2: What should professors and students avoid on Facebook? How can professionalism by teachers and students be modeled on Facebook?

The third category of findings pertains to pedagogical considerations when Facebook is used to support learning. This category aligns with research question 3: How can professors meaningfully engage with students on Facebook and thus support learning?

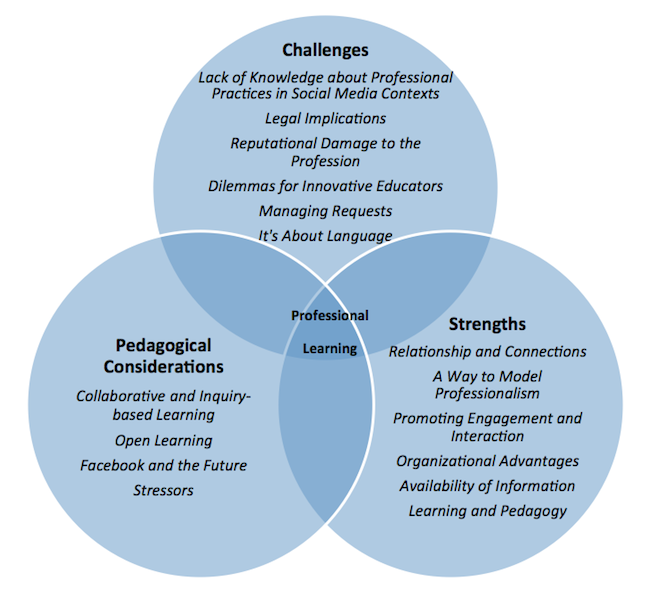

While every effort was made to ensure discrete categories with discrete elements, in some instances, there is overlay between the categories. In part, this overlay is due to the nature of interviews; in part, this is due to the interconnectedness of the areas of inquiry. This noted, in order to validate findings for the reader, quotations are included. Figure 2 provides a visual representation of key findings.

Figure 2: Themes and Sub-themes

Category 1: Lack of Knowledge about Professional Practices in Social Media Contexts

A number of participants commented on the need to teach students about professional behaviour on Facebook. Participant 21 summarized this notion as follows, “[Students] should be adequately taught and reminded of what is appropriate and inappropriate in publically accessible social media: teach about privacy settings, how potential employers may use Facebook and how they may interpret certain content.” It was also pointed out that students may need to be counseled not to share “too much personal information…the entire world has access to this stuff” (Participant 23) and to be sure to keep their profiles [including pictures] private (Participant 25).

Category 1: Legal Implications

Uncertainty about the legal implications of engaging with students on Facebook was raised as an issue. One participant commented:

I think that the faculty are tippy toeing around these issues just to protect themselves…. I think that it [faculty-student interaction through social media] is something that is going to be very necessary in the future and being connected to your professors is very helpful. They just have to find a way to make it work within the rules and guidelines of their organizations. (Interviewee 4)

The above observation emphasizes the dichotomy between students’ perceptions of their teachers as they struggle with the use of social media and the interest by some students in connecting with their teachers through social media.

Category 1: Reputational Damage to the Profession

Participants expressed concern that faculty-student interactions on publicly accessible social media sites may damage the reputation of the profession as a whole. In a profession like nursing, this concern is serious:

The professional status [of nursing] is, it feels like it’s so new. Everybody is just worried about our image. So that if something bad happens on Facebook about nursing than it could potentially ruin all the work that these people have done to get our status as professional. (Interviewee 4)

In professional programs, such as nursing, there is likewise fear of crossing boundaries through social media. Participant 11 remarked that “[i]t seems very unprofessional to be communicating with a professor over Facebook. Facebook is a social site; not one designed to be brought into the learning environment.” According to one participant, “professors should not engage with students on Facebook. It completely destroys the boundary between personal and school life” (Participant 27).

Additionally, concern was expressed about teachers’ need to respect students by not venturing into their social spaces. One participant made the following observation:

Facebook is SOCIAL media. Students hire professors to provide a PROFESSONAL service. In engaging on Facebook, I personally feel that professional boundaries become blurred. To me, this is the equivalent of walking up to a student in a bar…. (Participant 21)

Contrasting these views was the idea that, if professionalism is maintained, Facebook is a “useful tool” (Interviewee 4) that “should be done always” (Interviewee 2).

Category 1: Dilemmas for Innovative Educators

A further theme focused on the tension between trying new teaching and learning strategies, such as social media, and professional expectations. As one student indicated:

Because there is such a grey area of what you’re allowed to say or what you’re allowed to do, especially in the nursing program, having to maintain standards of practice, for nursing the professors are walking on a tightrope because they are worried that something is going to come back, the students are going to say something that might get them reprimanded or might get them in trouble with not only the CNO or the RNAO, but with the College. It’s really unfair because teachers who wanna get out there and help the students as much as possible and use the tools like social media and Facebook and stuff like that they are kind of hindered because they are worried there might be a backlash. (Interviewee 4)

Most significant in this pedagogical tug of war are boundary and privacy concerns. In no uncertain terms, one participant made the following point: “DO NOT INVADE THE PRIVACY ISSUES” (Participant 9). In the case of professional programs such as education and nursing, privacy of information pertains not only to university students and teachers. In education programs it also involves students in elementary and secondary schools and their families, while in nursing programs it involves patients and family members.

Category 1: Teachers Managing Friend Requests

The notion of a teacher accepting a friend request from a student was presented as unprofessional, “Professors should not be looking up their students; students should not be looking up their professors. Neither should add each other until after the program is done (as per professional guidelines on how long)” (Participant 21). Similarly, “adding [professors] prior to graduation should be avoided….I’d add – I’d try adding them after I was graduated, but at that point you’re a nurse” (Interviewee 2).

A further rationale for denying student friend requests is to avoid the perception of favoritism. At the same time, a couple of participants pointed out that Facebook includes options for connecting without accepting friend requests. For example, “having strict profession pages separate from personal and family pages as well as side groups like the one [Professor A] has created on professional growth is a great place to start” (Participant 23). Public pages can facilitate engagement of students with practicing professionals from different geographical locations. The participants were more receptive to Facebook groups than other more personal applications.

Category 1: It’s about Language

To maintain professionalism on Facebook, both students and educators should use professional language and tone and avoid personal discussion. Colloquialisms and short forms should also be avoided. The question of how contributions to Facebook should be monitored in order to ensure respectful interactions is a complex one. The teacher’s presence on Facebook was recommended as a way to promote professionalism:

If the teacher makes the group you know it’s a professional group and it’s a serious group…. I wouldn’t write anything unprofessional or say anything unprofessional because I feel like you're monitoring it. (Interviewee 2)

Another position was that, if the teacher does not monitor the site, he or she “could have someone [else] monitor the activity” (Interviewee 4).

According to participants, inappropriate and off-topic comments should be removed or otherwise addressed immediately. At the same time, according to some participants, not all teachers will want to take on this added responsibility even though monitoring is essential to keep students engaged; there is a “need to stick to the agenda and avoid any complaining or things off-topic” (Participant 18).

Strengths of Using Facebook

Category 2: Relationships and Connections

The idea of relationship building through Facebook emerged as important topic. As the following passage reveals, capacity for relationship and community building may exist through Facebook:

I think it’s a really important thing that teachers stay connected with students and provide them as much information as possible because, in a difficult program like nursing, it’s just it’s way too hard to deal with some of these things without being connected to your teachers and having a Facebook support group and stuff like that is very useful for a lot of students. (Interviewee 4)

As the interviewee pointed out, complex programs such as nursing may heighten the need for interaction between teachers and students as well as between students and other students.

Category 2: A Way to Model Professionalism

Recognizing that nursing is a social profession, some participants suggested that Facebook is a valuable place to model positive social interaction. At the same time, one recommendation was that students and teachers need to establish acceptable boundaries at the beginning at the course. Participant 18 indicated, “There needs to be mutual goals and boundaries set at the beginning with consequences by both faculty and students. Then, when problems arise you can revisit the mutually agreed upon boundaries and the consequences.” While there is no way to guarantee that everything said on Facebook will be professional, there is also no guarantee that everything said in a face to face classroom will be professional. Modeling professional behavior, however, can be a powerful learning tool. Participant 35 remarked, “The only thing that can be done is to model professional behavior. You can tell people what not to do but you cannot control poor judgment.”

Category 2: Promoting Engagement and Interaction

An educator’s greatest challenge is often maintaining engagement. This challenge exists in all kinds of classrooms: virtual, blended, and or in-person classrooms. The following passage points out how Facebook may be valuable in facilitating engagement, information flow, and organization:

The thing is Facebook in and of itself pretty much covers most of that [engagement] in my opinion. Facebook, first of all, is the one thing that every student will check, especially when they are procrastinating so information flow is very very quick. It’s also really already very good at organizing people into groups and just delivering the information. (Interviewee 3)

According to some participants, Facebook interactions do not need to occur on a daily basis. Daily interaction can be time consuming; as well, providing frequent meaningful feedback can be challenging because of the distractions inherent in Facebook, “I think it’s difficult on Facebook to meaningfully engage consistently just because there’s a lot of non-professional things going on Facebook” (Interviewee 4).

Interaction on social media sites when there is a learning focus will vary; however, with the greatest activity will be when an assignment is due. This phenomenon is not unique to Facebook since all students in all learning settings are likely to access course materials according to when graded tests and assignments are due. At the same time, there are ways of sustaining engagement on an ongoing basis. These strategies include “asking questions about weaknesses, provid[ing] positive feedback to comments besides just liking a comment, and “avoid[ing] short worded answers” (Participant 31).

Category 2: Organizational Advantages

Facebook enables organization of content in various ways including purposeful discussion groups. According to one participant with a nursing background, “I would say it would probably make the most sense to have probably five groups – one for each year and one overarching group to kind of cover the issues that affect all the years anyway” (Interviewee 3). As previously discussed, monitoring is important and participation is critical if there is to be value in discussion groups.

Category 2: Availability of Information

Facebook is a cost-free alternative to the discussion boards embedded in learning management systems. While students do not see the cost of using an institutional learning management system, it is there embedded in their tuition fees. One student noted that:

I find that there are a lot of tools - there’s email, there’s Moodle, or there’s the online websites that the schools offer that you can stay connected with your teachers – but I find that Facebook is more instant and it gives you really fast access to your teachers if they want to participate – and they don’t have to but if they do offer it then there are people who like to be connected to the social networking and at least you have that opportunity. (Interviewee 4)

The desire for immediate access to information is characteristic of the majority of today’s networked students. As they enter the post-secondary environment, they are, in general, already using and checking Facebook regularly for a wide variety of reasons. Some participants indicated that they “check Facebook more often than e-mail” therefore it “works better to reach a wider audience” (Interviewee 1). Additionally, Facebook can be quickly accessed by students on their mobile devices; this way “if a teacher [writes] something on Facebook I get that instantly because it goes straight to my phone” (Interviewee 2).

Pedagogical Considerations

Category 3: Collaborative and Inquiry-based Learning

Interaction through Facebook, according to study participants, promotes collaborative and inquiry-based learning. Students are fully able to ask questions and initiate discussions. When other students or the teacher responds, everyone sees the response which may engender further discussion. Discussions may likewise continue after the official closing of a semester, something that may not have happened without the use of Facebook.

This centralized approach to discussion and answering of questions can decrease the volume of emails generated when students have the same question. Students have also noted the benefit of being able “to get a global answer as opposed to having professors answer individual questions on email….[Professors can] answer broadly across Facebook” (Interviewee 4). The review of questions and sharing of answers through Facebook may be of specific benefit to shyer students. While class or cohort-wise information can be shared by the teacher through email lists and different tools with the learning management system, Facebook may provide a kind of access to information that students find helpful.

Category 3: Open Learning

With advances in social networking and mobile technologies, classrooms are becoming increasingly open. Classroom-related discussions on Facebook can lead to opportunities for dialogue with other learners and professionals around the world. As an example, the video applications of social media can assist all students in “learn[ing] an item or two…[including]… a better understanding of actual health care and what IS involved” (Participant 9). Generally, the participants reported that an exchange of information is more effective if an educator is present to guide discussions and filter inappropriate or inaccurate information.

Category 3: Facebook as the Future

According to the participants in this study, Facebook is part of our present and future. Interviewee 2 commented on the user friendliness of Facebook; anyone can “figure it out. Facebook is so big right now.” Similarly, a second interviewee commented that “used in a professional manner [where] friends and professors aren’t you know friending and private messaging on Facebook, …it’s a good tool cause social networking has taken over the media side of things within the past five, ten years …it is only going to become stronger” (Interviewee 1). Another interviewee (4) remarked:

Facebook is not going away. It’s just getting bigger and we need to embrace these tools because it’s just it’s really helpful to the student’s learning process and we don’t have to use it if we don’t want to, but the people who want to stay connected with their professors they have that opportunity with Facebook, but if the professors feel like they can’t connect with their students on Facebook because of a set of guidelines then we’re going to lose out and how can we grow as a profession if we’re not evolving with what the times are?

Category 3: Sources of Stress

Notifications from school-related groups, while they can helpful, can also be stressful. Participant 7 described the stress that Facebook notifications can generate:

Receiving multiple Facebook notifications from a teacher everyday only caused 10x more stress.… It is difficult to relax and take a break from thinking of school when even your Facebook notifications are school related. Not to mention, most have Facebook enabled on their cell phone, therefore [I] receive all those notifications at all times of day. (Participant 27)

Another participant commented on the volume of notifications this way:

Well personally all of my notifications for Facebook go to my junk email because way too much people [are] posting and commenting on things and I just put it in my junk folder it’s just, if I wanna see something I can go into my Facebook and read it…It’s just way too much information. (Interviewee 4)

Balancing these comments about the stress of Facebook are comments by others who viewed notifications as a kind of lifeline and who appreciated group notifications. Instant communication was seen as a benefit of Facebook by these students, who recommended that students could turn off notifications for a particular group.

A further stress derives from the dilemma that teachers face in deciding to ask students to use Facebook. In certain cases, the teacher may be hesitant to ask students to use a social media site where information can be sold for marketing purposes. There is also the issue of an equitable and fair learning plane: if not everyone wants to use it, should Facebook be used at all? Perhaps the best way of thinking about Facebook for learning is to think about it this way: “The people who want to use it [use] it [while] the people [who] don’t want to use it still have access to it” (Interviewee 4).

This study highlights the significant tensions found in divergent perceptions about using Facebook in nursing education. While the comments and views offered by study participants pertain to the use of Facebook in nursing education, as noted by one member of the research team, these tensions are not limited to the nursing; they are also being felt within the domain of teacher education and other socially oriented and caring programs. As teachers, care providers, and researchers know, professional boundaries are always a critical consideration when working with vulnerable populations and sensitive ideas.

Importantly, the ideas in this paper represent a starting point for further investigation of how Facebook and other kinds of social media might be used effectively to support learning in professional programs. When educators are aware of the strengths and challenges of Facebook use and take into account pedagogical considerations, it may be possible to create a highly professional learning and engaging situation (Figure 2). This noted, in conversations about the use of social media for learning, educators need to reflect deeply on how they may be able to connect with students and foster learning, all the while maintaining awareness of the inherent risks of social media use. Based on the study, it appears that Facebook may have a place in professional programs. Study findings point to benefits including timely access to information and a sense of community in complex learning situations as well as cost benefits and familiarity with social media in general. Such benefits necessarily need to be balanced against perceptions that social media are not, by design, learning tools. In addition, there are risks involving professional boundaries and dissemination of information inappropriately.

Perhaps some teachers’ and students’ concerns about Facebook and professionalism could be addressed through training and continuing education. Called Nethics or Netiquette by some, this field of study sensitizes learners to the nuances of communicating and interacting within virtual spaces. Taken to another level, individuals who practice ethical behaviours in their web interactions may become aware of iterative knowledge building, inspiration, and collaboration opportunities that Wenger (2004) suggests can occur in a virtual community of practice.

Aydin (2012) supports the use of Facebook in education because of its popularity among students and the various ways it can be used. Regrettably, insufficient studies have been conducted on the use of Facebook and other social networking sites in educational contexts. The literature that does exist is neither conclusive nor of sufficient quality to make confident decisions: some studies suggest that networking behaviors can enhance learning (Eberhardt, 2007); others argue that Facebook is a distraction and deterrent to learning (Johnson, 2010). Given the specific focus on nursing education in this paper and recognizing that learning is contextual, there is a distinct need for nursing-specific research on the use of Facebook in support of learning. Other professional programs also require the same research.

The one finding that does present repeatedly in this study is how Facebook increases student access to their teachers. This accessibility could be an important finding for nursing education. In nursing, safety in the clinical setting and student retention has been associated with real and perceived barriers in the teaching-learning environment. Current perceived barriers in the teaching-learning environment limits class discussions and the perceived approachability of the educator, which has been linked to safety concerns in the clinical setting (Killam & Heerschap, 2012). Based on this association, the idea that students may feel connected with their teachers through Facebeook may be valuable as a support and retention strategy as well as a learning strategy. As an example, when students are in clinical settings at some distance from the university such as rural and remote communities, using Facebook to connect learners and their teachers can keep students in touch with their home schools (Killam & Carter, 2010).Effective learning including distance learning has been associated with students’ sense of belonging and general connectedness with their peers and teachers(Carter & Graham, 2012; Carter, Rukholm, & Kelloway, 2009).

Work by Teclehaimanot and Hickman (2011) who found that men are more likely to approve of teacher-student interactions through social media than women may also be of relevance to this study. Extrapolating, the fact that nursing remains an almost exclusively female profession could be a variable in the findings of the described study. This point noted, the reality is that Facebook is an increasingly common element in contemporary society. At the very least, nursing students and their teachers need to understand how Facebook is being used in the broader health world (Are you Twittering, 2009). There is such a need for healthcare professionals to know how to use social media that Penn State Hershey Medical Center has developed a continuing education course targeting this very need (George, 2011).

Limitations

While the small sample size of this study is a limitation, points for and against the use of Facebook in professional education have been raised and can be used to incite conversation. As well, further research into the pedagogical merit of social media in teaching and learning is needed so students and educators in professional programs can make informed decisions about the risks and opportunities. This study then is a stepping stone to additional exploration of the possible role of social media in professional programs and university education more broadly.This study is a response to the reality that post-secondary students are already actively involved with and spending much time on social media and, in particular, Facebook. While other social media tools exist within learning management systems and externally through sites like LinkedIn, they are not as widely used by students. Given the power that that social media seems to have in the lives of university students, it seems reasonable for educators to examine its potential for teaching and learning. While every learning situation has its unique components, professional education is distinguished by the need for professional interactions and behaviours at all points.

This study suggests that no tool or medium unto itself enhances or detracts from professionalism. Instead, it is an outcome of the attitudes that human beings display and the actions they engage in relative to each other. Thus, with any learning management system, technology, or tool, it is important to use the system, technology, or tool judiciously. In the case of Facebook, expectations, mutually beneficial goals, and rules around its use need to be clarified through class discussions, contracts, and consensus-based policies. Additionally, educators at all levels and in all disciplines have a professional obligation to evolve their teaching pedagogies and to find ways to connect with their students in ways that build on the technological possibilities of the times. Considered this way, Facebook offers a promise of hope for such connections while, concurrently, challenging teachers and students to put their most professional selves out there in socially and pedagogically meaningful contexts.

Laura Anne Killam works at Cambrian College. E-mail: laura.killam@cambriancollege.ca

Lorraine Mary Carter is the Director, School of Nursing, Director, Centre for Flexible Teaching and Learning, Nipissing University. E-mail: lorrainec@nipissingu.ca

Rob Graham works at the Schulich School of Education, Nipissing University. E-mail: robg@nipissingu.ca